Service Employees Union Joins Move to Break Up UNITE HERE

The months-long tug of war within UNITE HERE continued in March when UNITE-controlled regional councils voted to leave the union. UNITE leaders embraced a partnership with the Service Employees (SEIU), and signaled they would form a new union, Workers United, to compete for members in HERE’s hotel and gaming jurisdictions—while snatching as many members as possible on the way out.

HERE leaders failed to stop the regional board votes in court, which they say are unrepresentative and violate the union’s constitution. At a mid-March executive board meeting, HERE allies vowed to recover ownership of the boards’ property and funds, and moved to slap lawsuits on officials who used union funds in the secession attempt. UNITE and HERE merged in 2004, but their clashes over control of resources and organizing strategy are reaching a fever pitch.

The votes to secede were cast by around 1,000 delegates nationwide, who are elected in some regional boards and handpicked in others. In Philadelphia, 14 of the 21 voting delegates were paid staff. At the Pennsylvania-wide meeting, however, hundreds of elected delegates voted unanimously to leave UNITE HERE.

The regional boards, called “joint boards,” scheduled a late-March convention in Philadelphia for Workers United, where the color scheme is sure to be some shade of purple.

SEIU President Andy Stern offered UNITE HERE a place within the Service Employees union in late January. HERE declined, but International President Bruce Raynor, UNITE’s pre-merger leader, pursued talks.

“We see this as having the big brother on the football team,” said a UNITE-side staffer.

The secessionist campaign—aimed at discrediting HERE leaders and the merger itself—was launched with help from Steve Rosenthal, a consultant with ties to SEIU. It included robo calls and mailings soliciting disgruntled members, and a website alleging lavish spending among HERE leaders.

Raynor cited organizing failures as the cause of the breakup. His allies compose a distinct minority on the executive board and among the union’s 460,000 members. He is expected to lose control of the union at its convention in June, prompting dozens of UNITE-aligned International vice presidents to resign in support of Workers United.

Citing Stern’s meddling in UNITE HERE affairs, HERE allies responded by preparing a breakaway from the Change to Win federation, and approving talks to rejoin the AFL-CIO.

BIG PURPLE

Soon after the secession votes, SEIU organizers joined UNITE leaders in shops, aiming to collect hundreds of thousands of signatures from both members and staff to prove support for the joint board secession.

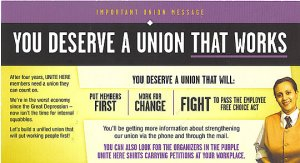

Members found mailers at their homes in early March, informing them to “look for organizers in the purple UNITE HERE shirts carrying petitions.” The petitions are a tactical ploy, not a decertification attempt.

To further strengthen the referendum, the Pennsylvania joint board is holding secret-ballot elections in every local, where members will choose whether to join Workers United. The New York/New Jersey joint board is holding similar votes for 2,000 members in its hotel division.

UNITE secessionists want to prove support in traditional HERE strongholds, which HERE promises to defend.

“We’re trying to make this union as internally strong and bulletproof as possible to fend off any member-grabbing,” says Jeff McCaffrey, president of Detroit Local 24’s gaming division.

John Wilhelm, who headed the pre-merger HERE, had sought to preserve unity even as it evaporated.

DON’T LEAVE ME HERE

HERE leaders want to extend what they see as the merger’s strategic advantages. As UNITE targets like laundry supplier Cintas grow their operations in hotels and casinos, HERE says the union should build from union strongholds and mount coordinated attacks on the corporations’ consolidating supply chains.

In a report defending the 2004 marriage, HERE leaders pointed to unprecedented contract gains.

“Over 3,000 laundry workers in Las Vegas now have free family health insurance—something that was unattainable for them prior to the merger,” said the report.

HERE argues that lengthy organizing campaigns (with heavy staff oversight) are often necessary to create strong worker committees in hotels. They prioritize contract standards over swift membership growth, and argue that the union must cultivate member-leaders who will build, maintain, and expand the union.

Wilhelm’s allies criticize earlier deals that SEIU and UNITE struck with service-sector employers that let the corporations choose organizing sites and created low-wage tiers at unionized companies. They predict several long-term organizing drives will produce 27,000 new members in casinos in coming years.

Joint board leaders, in response, criticize HERE for not pulling the trigger soon enough, and wasting money in the process. Results don’t arrive overnight, counters HERE. “Raynor’s claim to fame is a 17-year struggle to organize at [southern textile giant] J.P. Stevens,” said Pilar Weiss, spokeswoman at Las Vegas Local 226.

(TEMPORARY) RETREAT

While the union split in two, joint board officials filled in some trench lines at the local level, for now. UNITE forces gave up their takeover of Detroit’s Local 24, a 7,900-strong local made up primarily of HERE shops. The rationale was practical: Local 24’s leaders would have fought the creation of the new union.

Local 24 officers regained access to their offices, as well as the Motor City Casino, where the company had locked out union representatives while the factions squabbled. Elected local leaders also took back exclusive rights at the bargaining table.

The union’s crisis couldn’t come at a worse time for members at Detroit’s Riverside Hotel, where workers have been paid behind schedule for months. When workers have received checks, they’ve often bounced. “I don’t come to my job to do charity work,” said Carrie Shipman, a housekeeper at the hotel. Hundreds of protesters from a nearby labor convention flooded the lobby in February to confront management.

In all this, workers say their union representatives have been difficult to find.

WHY A NEW UNION?

“HERE never had a sound vision or functional plan for organizing in their core industry,” says joint board staffer Pete DeMay, who was dispatched to Detroit. He sees Workers United’s speedier, stripped-down organizing bringing in non-union casinos in the region, expanding a base among casino dealers, and building density in Chicago hotels, where DeMay says about half of the city’s hotel workers lack a union.

HERE officials say UNITE’s new partnership with SEIU is illegal, and reversible through the union’s democratic process—or in court.

Other union leaders are aghast that the bitter fight could drag through the courts. With public support for the Employee Free Choice Act in the balance, presidents of the Steelworkers and Autoworkers pleaded for the union to end the merger and seek “reasonable alternatives” to open warfare. The UAW also announced plans to work with SEIU in the gaming industry.

“We’re not relinquishing that jurisdiction,” said DeMay. “You can call it raiding if you want—call it what you want to call it.”

Ernest Lemond resigned as president of Local 24’s airport division to support Workers United. “People should have the right to vote for the union they choose, and if they want to come to a new union, let them,” he said.

Comments

What's not been said

Every union in the country is at risk of the same thing -- members losing confidence in the organization and breaking away to form a new union, leaving to join a different union or decertifying to no representation at all.

Make no mistake, the vast majority of UNITE HERE members are not contented union members. Former UNITE members have chafed at the cultural changes and have felt shut out of decision making -- not just high level staffers and officers but local level officers and activists.

What Wilhelm can't seem to grasp -- you can't bully and litigate loyalty and trust -- you have to get up every day and earn it. You can't effectively shutdown and shut out a significant minority and expect them to just get in line. When folks don't feel heard, served or valued they leave. And it's the job of the leadership to think through the concerns of the minority and truly address those concerns, not just pay them lip service.

The merger never worked for a range of reasons not the least of which was the uncompromising arrogance of both presidents.

More hat than cattle

The workers united "union" delegates meeting in Philadelphia "represent" approximately 75,000 members of Unite Here. Several joint boards who had supposedly sided with Raynor's dissident faction chose not to participate in this mock convention and several large former HERE locals who were part of joint boards that did participate, pulled out of their joint boards. The voting leading up to the convention was a haphazard mix of partial joint board votes (some of the joint boards were composed of as few as 20 people, the majority of whom were staff rather than elected members) which included converting meeting sign-in sheets as "petitions" calling for a convention.

The real story here is the impressive media/communications juggernaut that SEIU has built up -- and corresponding disconnect from its own members and locals -- so that it could create the impression in the press and blogosphere of a reality that simply doesn't exist.

The other real story is that the HERE side of UNITE HERE has achieved 50% density in gaming nationwide and 20% density in hotels nationwide -- both are considerable achievements with generally high contract standards. SEIU by contrast -- though there has been a proud history of dedicated organizing in its core healthcare sectors, has only managed to achieve 9.5% density in hospitals and 11% density in nursing homes nationwide. Its dream of a national healthcare union and achieving majority density in healthcare are great dreams and ambitions. Stern is famous for asking to be judged by results rather than intentions. By his own measure, HERE has been far more successful than SEIU in organizing and establishing a high level of standards for service workers in their respective core industries. HERE has failed to amass the quite impressive SEIU media/communications/messaging prowess -- however, the growing strains within SEIU will show that a PR machine is a poor substitute for a union with a clear organizing focus in its core industries, a clear set of standards which are the measure of contract gains, and a structure which encourages rather than sees as incidental the ownership of the union by an engaged rank and file membership.

Lastly, Workers United, as of yesterday, was actually absorbed into SEIU and does not exist as a stand alone national union. See the Workers United website which states the vote resulted in Workers United becoming a "conference of SEIU."

The federal government is

The federal government is showing 1.8 non-managerial jobs in the hospitality sector in 2006. So by my math, 20% would be closer to 360,000. And that's after HERE has had 120 years of near exclusivity in the turf. Nothing to be all pumped up and proud of there.

SEIU hasn't been organizing in healthcare all that long and shares both the professional and service turf with a number of other unions organizing in healthcare.

I'd also want to ask an HERE organizer about all the time, money and energy the union has put into GESO -- what the HELL are ya'll doing organizing grad students and researchers in the first place? Shouldn't the higher education sector be the exclusive province of the AFT?

So here's what I don't get -- if Workers United (independently or as a division of SEIU) can get out there and get some hotel workers organized, and they believe they can do that more quickly than as members of UNITE HERE, um, what's the beef? HERE has had over a century to organize these workers -- isn't it about time someone got around to it?

So what if Stern is just trying to build an empire? At the end of the day doesn't that just make for more organized workers? Aren't there plenty of hotel workers to go around? Enough for HERE to double it's density in the next 120 years without ever having to directly compete with SEIU?

20% density in what hotels?

If UNITE HERE has 20% of all hotel workers in this country in the union, I'll shine Andy Stern's shoes.

There are, if my sources are correct, somewhere between 1.5-2 million hotel workers in the USA.

There are about 100,000 (give or take) members of your union's Hotel Division. And by "your union," I mean the union that you work for, not a union that you are a member of.

So what is that? 5-7%?

Not that I disagree with your overall argument. I mean, your side's PR may not be as high dollar as Raynor's, but you generally have the advantage of slightly more truth (or is it slightly less bullshit?). Just not with this particular number.

What an utterly disingenuous

What an utterly disingenuous “debunkment”, Mr. Anonymous. What you fail to mention is that the number you quote is not the total number of union-eligible hourly workers in hotels but the Bureau of Labor Statistic's total employment numbers for the ENTIRE “Traveler Accommodation” sector of the economy (1.77 million in 2007). Hundreds of thousands of workers outside of this category are included: management employees, travel-related professionals, non-hotel food preparing staff, etc. With about 10 minutes of research any reasonable observer can find this on the DOL website. Twenty percent is more credible than the 5-7 percent you claim.

And frankly in general, the UNITE HERE majority's claims not only hold more water than the Raynor loyalists and their Big Purple puppet masters—they point out the latter's abandonment of the few (if important) positive planks of the “Reform from Above” industrially focused unionism of the New Unity Partnership of even a few years before. How on earth do their bureaucratic general-unionist manueverings build any real power for workers in the hotel industry? What effect will this have on building real on-the-ground contract and organizing campaigns in a year when most of all those hard-fought for major hotel contracts expire? How do they even think they will exert effective control over worksites where thousands of rank-and-file members are to be shifted away like so many pieces of meat?

I would say the Bush-like hubris of SEIU and UNITE's top leadership was tragic—if I didn't recognize what history tends to do such over-reach. The sooner the rest of us in the labor movement help them along the path to the rubbish heap the better.

Chris Kutalik,

Amalgamated Transit Union

unitehere

From where i sit, The view is pretty clear. The door to local 24 in Detroit was always open when I came around a couple of years ago. I found alot of people willing to help those who were willing to help. The whole internal union struggle has everything to do with one group exerting its will on another. Never a recipe for harmony.The S.E.I.U. and the U.A.W. teaming up to assault another organization is everything corporate america can hope for. I wouldn't be surprised if the Corporate world doesn't hire thier own organizers to start another union to assault the S.E.I.U. Why not? Fuck it, lets kill the labor movement now while it's poised to either thrive,or die. Hey Stern wake up. Raynor, you don't have to pull down the temple walls when you go. Just go.

Go IWW! Everything the

Go IWW! Everything the labor movement once was, and should be again.

Professional unionist. How flattering.

As a friend of Mr. McCaffreys I can with certainty say that he would be truly flattered at being called a professional unionist. The persistent rumor that he was imported from out of town and is a professional unionist is truly strange to me. I know for a fact that he was raised in Berkley, MI just outside of Detroit. He worked for a railroad when he was younger, just out of high school really, and that was his only experience with any other union(a service model union at that). I met him in 2002 and became very good friends with him. He had moved to Atlanta, Georgia and we met while we both worked at a non-union restaurant. When he married and started a family he moved home. To Michigan. This slanderous rumor first came to my attention in a mailing from the Chicago Midwest Regional Joint Board. It is purely made up. My defense of him means absolutely nothing, of course. A lie was told in writing and no matter the actual truth, when it is in black and white, people like the writer above will prefer to believe the lie. As for running unopposed, that is yet another lie. The Casino division election featured four candidates for president.

Get real.

I am a member of UNITE HERE Local 2 in San Francisco, and have been since 1976. From where I sit, the choice between Wilhelm and the Raynor/Stern axis is very easy. Wilhelm represents steady progress in organizing our industry, and steady improvement in union democracy. Sure, the HERE side has its problems, but what union these days doesn't? On the other hand, Raynor and Stern represent business unionism and opportunism in full display. Not a hard choice.

It is sad that all we have

It is sad that all we have for unions is a bunch of butt kissers. Forget fighting the boss we are to busy fighting each other

The union bosses are a bunch of GD jerks who care only about themselves AND SHOULD NOT BE ALLOWED TO make choices that screw us all over!

UNITE HERE

I hope people don't miss the forest for the trees here. Big picture: SEIU is using Bruce Raynor as an excuse for SEIU to raid the hotel/gaming/food service jurisdiction of UNITE HERE. Once again: SEIU, which has millions of health care workers and janitors left to organize, yet is losing tens of thousands of the members it already has right now in California, is choosing to declare war on UNITE HERE - a highly successful organizing union, and a longtime ally of SEIU. Anyone in the labor movement with a soul or a conscience knows they didn't sign up in order to do this kind of thing. I'm interested to see if any SEIU staffers have the guts to refuse to raid UNITE HERE members or turf. If they don't, it will be sad for two reasons: because the labor movement will be saddled with all-out war between two of its strongest organizations, and because the arrogant SEIU would-be raiders will find out what happens when you take on the "member-leaders" that UNITE HERE develops every day.

This is too too rich

SEIU on EFCA:

Its about democracy. Workers should have the right to choose a union by simple majority sign-up.

Chamber of Commerce on EFCA:

Card check is the death of democracy. Workers will be intimidated and harassed into signing cards by organizers. Only a secret ballot preserves democracy and management must have ample time to "fully inform" workers about their choice.

NUHW on Kaiser workers:

The Kaiser contract provides for union recognition through majority sign-up. A majority of Kaiser workers have signed up to join (re-join) NUHW.

SEIU on NUHW/Kaiser:

Those cards/petitions are undemocratic. This a union raiding another union. And those workers were harassed and intimidated into signing up for NUHW. Only a secret ballot will preserve democracy at Kaiser and SEIU needs ample time to "fully inform" the workers about their choice.

HERE on SEIU:

There has been a campaign of harassment and intimidation by SEIU in an attempt to raid HERE members. Workers United (UNITE) is just SEIU raiding a union outside its jurisdiction. Oh and by the way, there is already far greater density in the gaming and hotel sectors than in the hospital and nursing home sectors. Shouldn't SEIU concentrate on building their union?

SEIU on HERE:

Its about democracy. Workers should have the right to choose their union through simple majority sign-up.

Loop and re-play .......

Let the membership vote

Here's a question --

would Wilhelm agree to have the membership vote on all this? Shop by shop -- two choices -- stay with Unite Here -- leave to join a new union. Or how about this? A union funded representative survey conducted by an impartial outside polling firm to at least get a snapshot of how the members feel about their union and the direction they'd like to go.

Funny, but while he likes to throw around the word "democracy," when it comes down to it he refers back to the lawyers interpretation of the constitution and the power of the "democratically" chosen executive board without ever recommending the members themselves directly decide their own fate. Hmm.

which way's up?

See, the problem is that without being inside the union and having access to all the information, you can't figure out which way is up. Recently I was a staff member of UNITE-HERE, and I can't figure out what the hell is going on. Even all my friends that still are staff for the union don't know the whole story.

All of this is a stupid b.s. power struggle between Raynor's faction and Wilhelm's faction. They don't give a shit about what their workers or low-level staff think. There's no right 'side' to be on. HERE's a cult gone off the deep end and UNITE's a dying union making a deal with the devil (Andy Stern) to preserve their power.

All I can say to folks still in UH - get with the members, take leadership from them, and make sure they don't get fucked throughout this whole process!

the members lose

Yup, the members are the big losers in all of this but, hey, what else is new? Show me the union out there where the power players actually give a shit about the welfare of the members. To the fat cats, the members are numbers on paper, stories for the newsletter and props for the camera. Nobody even gives a damn about earning their votes anymore, having invented countless ways of manipulating and controlling union elections. And when the members aren't needed to promote the agenda? Out of sight, out of mind, probably in a broken down bus on the side of some freeway begging an organizer in training for a second god damn juice pak.

And, please, Stern didn't invite that mindset and he's hardly the most blatant practitioner. The labor movement is chock full of oily local petty potentates, high level staffers who wouldn't know a member if they were bit by one and big boys far better at slinging "it's all about the members" rhetoric than actually ever living it. And running around underneath them are the staffers who give a damn (and thus eventually burn out and leave) and the staffers who are in it for a paycheck and sleep well at night no matter what they are asked to do to earn it.

Why? BECAUSE THE MEMBERS DON'T GIVE A DAMN. They are too busy to make a meeting or demand one. They vote how someone else tells them to vote, if at all. They TOLERATE garbage so they get more garbage in return. "It's too depressing!" to take back their own GD union. They spend hundreds a year on a product they know less about than their $3 box of corn flakes.

So Andy is but again the Labor Notes boogieman trampling the rights of good decent honest grassroots real union people like...who again?

It's ALL fucked up, kids -- unions, corporations, non-profits, governments -- on top, on the bottom and in the middle. Oh my! A screwed up union story full of greed, power mongers and half truths where the members get screwed!

It must be Tuesday.

Amen sister or brother!

Amen sister or brother! It would take those of us that have actually worked in the labor movement for years to really be able to say "what the f***" I mean really, I have worked for several unions and associations to find that the retoric, bs, power plays and lack of democracy are everywhere. It is a sad day in labor because those of us that give a s**t struggle to stay and fight while knowing the leadership is rotten to the core. Most leadership has lost touch membership and reality! I mean look at the mergers, look at the bigger is better mentality. Do the members really vote on these changes? Hell NO! It is a struggle inside wanting to fight and make things better while the labor leaders are no better than the corp. leaders they pay us to fight. The lesser of two evils!

DON'T BLAME THE VICTIMS!

"BECAUSE THE MEMBERS DON'T GIVE A DAMN."

EXCUSE ME????

Unions are set up to rigidly exclude workers from the internal lives of their unions!

UNITE's predecessor union, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, used to have a constitutional ban on anybody other than business agents, union lawyers and other staff running for office, a rule imposed in 1910!

And they're not the only union like that.

So I'm with you with your attacks on union chiefs and union staffers - but you really need to quit it with your attacks on workers!

HERE- so disingenuous

HERE is really citing stopping industrial launderer Cintas from expanding into hotels as a reason to save the merger? The Cintas campaign began pre-merger and HERE has done nothing to get the non-union sweatshop out of their hotels. NOTHING. They had four years to take action and fight for safe union linen and uniform suppliers in their hotels, but choose not to. Laundry workers across the country have fought for and won free family healthcare and good wages and they didn’t need or get the support of the Vegas Culinary Union or any other HERE local to get it.

JUST CALL IT WHAT IT IS

Power and greed, its just that simple. You didn't hear Raynor complaining about the Unitehere merger until he realized he might not win in the upcoming democratic process coming up at their convention in June. He is no better than the companies he has claimed to be fighting his whole career. If he wants to "Wage War" in his own fit of self-interest, then the long term suffering he is going to cause the very workers he is supposed to represent just shows what really important to him. Power and Greed.

The issues on the ground

Currently, I am a member of Unite Here or what may be left of it at Yosemite National Park. Before I arrived at the park the workforce was represented by SEIU now Here will swoop in and claim the representation. It is very sad to see this happen for it was not the local union organizing which engaged me it was the massive visibility around the country which did. As for the actual local representation I will admit it is hard to tell if there is any. Our shop stewards are not on union payroll and the company keeps them busy with company jobs but with such turnover rate in a national park I can understand the challenge to improve conditions for longtime park employees.

Actually the problem with

Actually the problem with Labor Notes these days is that it reads way too much like mainstream so-called "objective journalism". Labor Notes used to sound like the scrappy advocate on the street corner. Now much of it is so much white bread, bland and a bit distant from the people it covers.

The hacks like the obvious UNITE tool above have way too much of a soapbox thanks to their access to countless millions of $ of their members' money. And the mainstream press already has it's bs "fair and balanced" coverage tucked away in the business section.

So when is Labor Notes going to get off of smug basking in TV spots and get back again to fighting for the Little Guy?

Whatever Steve

I don't quite get why Steve Early bashes Labor Notes under a pseudonym that everyone knows is his. More proof that Steve gets along with no one -- not even Labor Notes! No one is cynical enough about the workers' movement for Steve's tastes.

I thought the article seemed

I thought the article seemed pretty objective and balanced.

*shrugs*

bias

Well, a few word choices jump out at me –

Unite leaders “snatching” members on the way out for one example.

As I read the article, Raynor is only interested in maintaining his “control” over the union (which he apparently doesn’t actually have now) and good brother Wilhelm has only sought to “preserve unity”.

Apparently there is some question as to how well the members were represented in the Joint Boards’ votes to secede, but not in how delegates are assigned or elected to the Unite Here executive board where Raynor “allies” are the “distinct minority”.

The author goes on to devote six paragraphs to unsubstantiated claims from the Wilhelm “report” on organizing, with a one sentence rebuttal of it’s assertions from the other side.

The author then conjectures on the “practical” rationale” for the joint board’s “takeover” of local 24, when the “takeover” was initially only about the removal of STAFFER Joe Daugherty from his STAFF director position. The author also forgets to mention that Daugherty, the “elected” president of 24, executed what amounted to his own “takeover” of 24 by running unopposed for the office while never having worked a day in a member’s job while blocking long time dues paying members from running in opposition to him. And never mind how Las Vegas forces have funded and staffed the fight in Detroit or how the members at the Riverside have been ignored and misrepresented for years – the author would have us believe everything was keen in Detroit until the “takeover” when he certainly knows better.

Labor Notes seems patently disinterested in the years of mismanagement and corruption at local 24 under the safety of Wilhelm’s beefy wing, and how that has profoundly damaged the rank and file members the paper claims to stand for. A little investigative journalism there? Why bother.

Too bad you haven't talked to the members

of local 24 and so many other UNITE HERE locals across the country held in the feudalistic grasp of Wilhelm style "unionism". If you did, the Labor Notes readership would have a much stronger understanding of just how undemocratic a union can be.

Just a few choice examples from the thousands out there --

--ratification votes that take place only at the union hall, two and a half hours away from the worksite on public transportation, that make it impossible for workers to participate.

-- "elected leadership" like Mr. McCaffrey, professional unionists that run unopposed after only having worked in the shop for less than a year and being imported from out of town, while legitimate members interested in higher office, like Mr. Lemond, are coerced into not running or excluded on convenient technicalities like lapses in dues.

-- local 24 business reps that receive special discounts from management (in particular the Riverside), cuss out members in front of customers, and function at the table only to aid management in forcing concessions while as standard practice never standing WITH the workers or fighting for true member gains at the table.

-- a rep and steward structure set up not to represent the members, but suppress the members and keep them in line on the job

Next time you write one of these pieces -- please, please, try calling a couple dozen local 24 members AT RANDOM and interview them on their union representation -- not just over the past three months but over the past eight years.

Your bias in this article is evident and disturbing. I always thought Labor Notes was a true champion for grassroots democratic unionism. Do your homework.

Amen

Tell it like it is!