100 Years Ago, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters Changed Black Politics

The fact that the meeting was even happening was enough to produce an air of subversive excitement. One hundred years ago on August 25, 1925, Black sleeping car porters, hoping to form a union at the Pullman company, packed the Elks Hall in Harlem. Company spies were probably in the audience as well.

Socialist A. Philip Randolph led the meeting, making the case that a union was the only way to deal with their grievances and reclaim their manhood. This gathering initiated a 12-year struggle to form the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) and win a first contract against a corporate giant.

“The Brotherhood,” as many members affectionately called it, would become a vehicle to educate Black communities about labor unions and challenge corporate domination, and an institutional anchor for waging civil rights fights and developing activist pressure tactics. Its embodies the deep historical connection between the labor movement and civil rights.

‘TRAINED AS A RACE’

In the late 19th century, industrialist George Pullman designed luxury train cars to transport passengers across the country. The genius was in making this service available to the middle classes, not just the wealthy elite. The idea took off, and by 1895 Pullman had 2,556 sleeping cars traveling 126,660 miles of track. At its peak, the sleeper cars hosted 100,000 a night—more than all of the country’s major hotels combined.

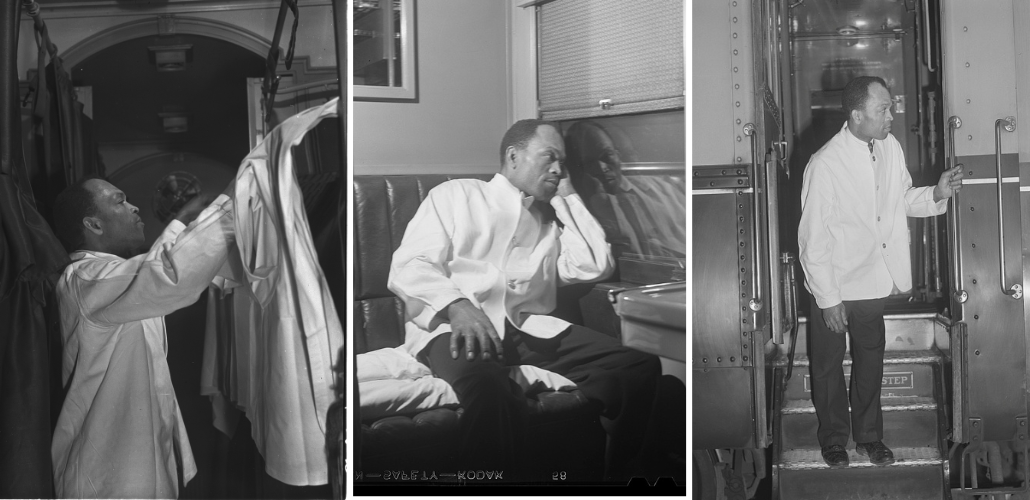

The key to this luxury was not just a bed to lay your head on and some food to eat. Passengers would have their own personal servant: the Pullman porter. Cynically, Pullman reserved these jobs for Southern Black men, preferably the formerly enslaved, explaining how they were “trained as a race by years of personal service in various capacities” for this job. In a further insult to their dignity, most porters were referred to as “George,” harkening back to the days of slaves being named after their master.

The expectation of complete subservience was reinforced by the fact that porters relied mostly on tips for their wage. The surest path to a fat tip was catering to the customer’s every need and enduring each humiliation with a smile. Shining shoes, running a bath, mailing letters, lugging baggage, and looking the other way at indiscretions were all in a day’s work. Former NAACP President Roy Wilkins, who worked as a Pullman porter as a young man, said they “worked like house slaves on roller skates.”

The hours were brutal. On average a porter had to work almost 350 hours per month. Especially in the early years, they had a hard time getting more than three hours of sleep at night while on a trip. Porters had to pay out of their meager wages for a work uniform and supplies like shoe polish.

But despite these conditions, sleeping car porter was viewed within Black communities as a prestigious job. Many porters used the job to pay for college; from Thurgood Marshall to Malcolm X, a list of former porters reads like a Who’s Who of Black history. Beyond economic stability, the porter represented well-traveled sophistication.

MOMENTUM BUILDS

Previous organizing efforts had been snuffed out, at first through brute intimidation and eventually through clever co-optation by the Employee Representation Plan, a company union set up in 1920, which responded to the worker rumblings by instituting an 8 percent wage increase.

One of the ERP officers was a respected porter named Ashley Totten who read A. Philip Randolph’s socialist magazine, The Messenger, and listened to some of his soapbox speeches. He and some other reps were fed up with the ERP’s ineffectiveness, and thought Randolph could be the perfect outsider to agitate porters without fear of company retaliation.

Randolph saw in the porters’ struggle a symbol for the strivings of all Black working people. Believing they were “made to order to carry the gospel of unionism in the colored world,” he threw himself into his newfound leadership role.

Initially the campaign gained momentum. At the first mass meeting at the Elks Hall, Randolph proposed demands of $150 per month in wages, a limit of 240 hours work per month, and an end to the demeaning practice of tipping. The next day 200 New York porters streamed into The Messenger office, which now served as union headquarters.

BREAKING THE WEB OF PATERNALISM

To go up against Pullman and win, the union would have to not only persuade workers, but also wage a crusade for the hearts and minds of the communities where workers lived, and shift the balance of power within important Black institutions. Over the decades Pullman had perfected a web of paternalism to ensure the loyalty of key Black constituencies.

The company was seen as benevolent for consistently employing Black workers, an image reinforced by its substantial financial support of Black institutions like the Urban League and churches, where anti-union propaganda was spread from the pulpit on Sundays, and Pullman-sponsored social outlets like baseball games, concerts, and barbecues.

Still, the BSCP began to make inroads. Women’s political clubs helped connect Brotherhood activists to a broader political network. Ida B. Wells was active in this scene and organized the Wells Club and Negro Fellowship League, where discussions were had on Pullman unionization.

The BSCP Women’s Auxiliary, consisting mostly of the wives of Pullman porters, gave vital support. Often women were the ones who went to meetings, to prevent retaliation against male workers. Auxiliary chapters organized study groups and fundraisers.

Milton Webster, the hard-nosed, politically connected head of the Brotherhood’s Chicago division, put together a Citizens Committee to build support in the city’s Black community. This group organized regular “labor conferences” that brought allies together and stimulated deeper thinking about the role of Black communities in the economy, serving both an organizational and ideological role. By 1929, nearly 2,000 people attended these gatherings.

The union portrayed its fight as a continuation of Black peoples’ longstanding quest for civil rights and equality. One union bulletin read, “Douglass fought for the abolition of chattel slavery, and today we fight for economic freedom. The time has passed when a grown-up black man should beg a grown-up white man for anything.”

BATTLE WITH THE COURTS AND THE COMPANY

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Brotherhood leaders had to build and maintain membership while a lengthy battle with the courts took shape. By June 1927, the Railway Labor Act mediation board recognized the union as representing a majority of Pullman porters. But the Brotherhood still didn’t have the leverage to force the company to the negotiating table.

Randolph felt that if the porters presented a credible strike threat and created a national crisis, the President of the U.S. could be called on to step in and force the company to bargain. The union threw itself into strike preparation, and by the spring of 1928 claimed that over 6,000 porters had voted to strike. But Pullman called the bluff, saying they could easily be replaced. Randolph, after getting pressure from AFL President William Green, decided to call off the strike.

The union had shown its hand and lost. The disappointment of the aborted strike combined with the pressures of the Great Depression put the union in a death spiral. Membership fell from a peak of 4,632 in 1928 to 1,091 in 1931. These were years of intense personal struggle for the union stalwarts who stayed committed. Randolph conducted union affairs in tattered suits, with holes in his shoes. He often had to pass the hat at the end of meetings in order to get from one place to the next.

But the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 threw a lifeline to the Brotherhood. In 1934 Roosevelt signed an amendment to the Railway Labor Act which included porters, banned “yellow dog” contacts with company unions like the ERP, and required corporations like Pullman to negotiate with unions that represented the majority of their workers. Membership shot back up, from 658 in 1933 to 2,627 in 1934.

Prominent Black organizations like the NAACP and Urban League began to focus more on economic issues and embrace unions, thanks to Randolph’s relentless propaganda. Both organizations publicly endorsed the Brotherhood, and on July 1, 1935, the union won an election to represent the porters, 5,931 to 1,422.

Twelve years to the day after Randolph’s first public meeting with porters, on August 25, 1937, the Pullman Company signed a collective bargaining agreement that fulfilled many of the union’s initial demands and changed the lives of porters. The working month was reduced from 400 hours to 200, the wage package increased salaries by a total of $1.25 million, and a grievance procedure was established. The Chicago Defender described the contract as “the largest single financial transaction any group of the Race has ever negotiated.”

ANCHOR OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

Randolph could never disentangle his two roles as union leader and civil rights crusader. Having established itself as a leading force in Black labor, the Brotherhood used its institutional muscle and vast social networks to stimulate political activity against racial inequality.

During World War II, when Black workers were locked out of defense industry jobs, Randolph called for a March on Washington to secure these jobs for Blacks and end segregation of the armed forces.

March on Washington Movement chapters were established in cities across the country, and they were strongest wherever there were large BSCP locals. Members led the effort; the union offered meeting space and logistical support. Randolph held large rallies across the country, while porters spread the word on their rides.

Worried about the threat of a large domestic disturbance just as the U.S. entered the war, Roosevelt blinked and signed Executive Order 8802, banning discrimination in defense industries, and established the Fair Employment Practices Committee.

After this win, Randolph called off the march but kept the March on Washington Movement in place to enforce the order locally. It thrived in BSCP stronghold cities like Chicago, St. Louis, and New York City, establishing the social networks, protest strategies, and political confidence that would blossom in the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

In fact, the BSCP played a central role in the catalyzing event of that movement: the Montgomery Bus Boycott. E.D. Nixon, president of the Montgomery BSCP, bailed Rosa Parks out of jail after her arrest, and the BSCP union hall became the boycott movement meeting space. Nixon’s extensive organizing experience and broad social network proved invaluable.

Pullman porters, the itinerant eyes and ears of the civil rights fight, reported lynchings to groups like NAACP. The union gave money and legal support to higher-skilled Black railroad workers like firemen, brakemen, and switchmen fighting to end employment discrimination and keep their jobs. When the 1963 March on Washington fulfilled A. Philip Randolph’s original idea, the BSCP gave $50,000.

LESSONS FOR US

The Brotherhood was not just a union of Black workers. It was a movement for Black economic advancement and social equality, grounded in an economic outlook and a working-class base. Its experience offers lessons for organizers today on political education, building broad public support, and making a union the anchor for larger political fights.

Last February, 150 members packed the Teamsters Local 100 hall in Cincinnati, Ohio, for a Black History Month event. Many were people who rarely attended union events, but this social networking planted the seeds for a contract campaign at Zenith Logistics, a third-party operator for Kroger where most of the workers are Black and Latino.

They went on to gather contract surveys in multiple languages, wear “Will Strike If Provoked” shirts, and clock in all at the same time in front of management. They won a contract with the best wage and benefit gains they’d ever seen, along with language protecting members from ICE raids. Some are now becoming shop floor leaders and proudly attended the Teamsters for a Democratic Union convention.

One can’t help but see the spirit of the Brotherhood in them.

A longer version of this story appeared in Jacobin, where Paul Prescod is a contributing editor.