Review: Dying for an iPhone: Apple, Foxconn, and the Lives of China’s Workers

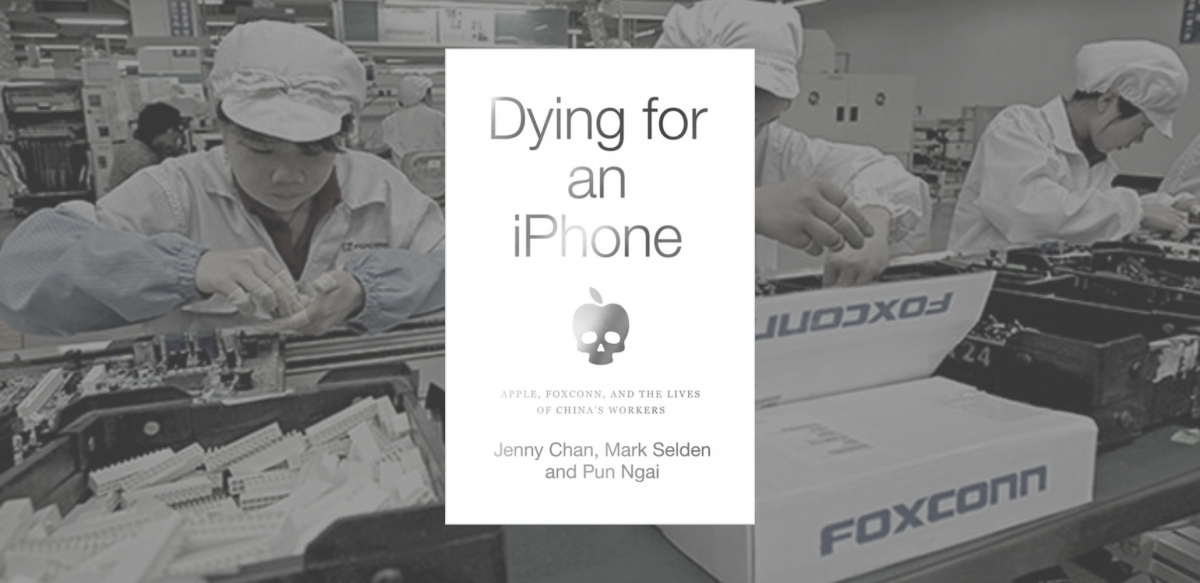

Dying for an iPhone: Apple, Foxconn, and the Lives of China’s Workers by Jenny Chan, Mark Selden, and Pun Ngai. 2020, Haymarket Books, 304 pages.

Jenny Chan, Mark Selden, and Pun Ngai did extensive field research for almost 10 years to produce Dying for an iPhone. The result is a riveting account of the lives of workers on the production line, but the authors go further to reveal the human, social, and environmental impacts of the iPhone's manufacture.

They argue that Apple and its main supplier of iPhones, Foxconn, are prime examples of the destructive nature of capitalism, and they critique Apple’s marketing strategy of “[encouraging consumers’] to believe that in buying their products they can achieve their dreams of love, entertainment, and success.”

WORKING CONDITIONS

The authors' multiyear research began when a spate of Chinese iPhone workers' suicides in 2010 placed a spotlight on their working conditions. Well-documented in the media and by labor rights groups, those conditions include exhausting work, disciplinary management style, and increasing pressure to produce in short time frames, all for meager wages. The Foxconn factory in Chengdu, which produces the iPad, saw an explosion one night when aluminum dust in the factory was ignited.

Foxconn provides shared dormitory rooms at the factory, and by doing so, “the workplace and living space [are] compressed to facilitate high-speed, round-the-clock production.” By combining the working and living environments, factories exert greater control and easily extend work hours to keep up with production. Workers experience broken marriages, are separated from family, and are forced to leave their children behind in home towns. Life is monotonous. This is the dormitory labor regime that Pun Ngai described in her earlier works.

The authors juxtapose Apple’s public relations statements with the reality of working conditions.

THE GOVERNMENT'S ROLE

They make note of the Chinese government's integral role in the exploitation of Foxconn workers, for the sake of maintaining economic growth and attracting investment to local areas. One way is to send student interns from vocational schools to work in the factories; in recent years Foxconn has relied extensively on such interns, who do the same work as regular workers. The Henan provincial government, for example, paid schools a fee of 200 yuan per person to arrange for students to intern at Foxconn.

To push back against blatant violations of their rights and interests, Foxconn workers have launched strikes and protests and even threatened suicide. A worker who participated in a 2011 slowdown on an Amazon product line at Foxconn Longhua complained: “We’ve been pushed like mad dogs to meet impossible production targets!” But instead of supporting workers, the official union, government officials, and police have intervened mainly to pacify and even to suppress worker struggles.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

In 2012 a riot took place at the Foxconn plant in Taiyuan. Workers were putting in 130 overtime hours a month, did not receive paid leave when sick, and were constantly pushed to work faster. Riot police were called, and several workers were detained and some beaten. In 2018, when contract workers at Foxconn Zhengzhou protested over unpaid bonuses, the government-controlled union failed to support them. Although Foxconn had previously announced it had held union elections, these were “conducted as a formality,” the authors say, and genuine democratic elections are yet to be seen.

The courts have stood on the companies' side. The authors focus on efforts by workers to take grievances through legal channels, with the number of labor arbitration cases increasing over the years. But legal costs are high and processes are lengthy, making victories difficult. The authors tell the story of Zhang Tingzhen, who sought compensation after falling from a ladder at Foxconn Longhua and suffering severe brain injuries. Foxconn Longhua asserted that Tingzhen was employed by the Huizhou facility so it was not legally responsible for compensation; the court ruled in Foxconn's favor.

THE ENVIRONMENT

The authors dedicate a chapter to looking at the tech industry’s impact on the environment. Electronics factories have been known to pollute communities with toxic materials and chemicals and to poison their own workers. International outrage prompted Apple to say it would conduct “environmental audits,” but the tech industry has yet to take a more stringent stance when it comes to environmental sustainability.

The book reveals the limitations of “corporate social responsibility” schemes. Apple consistently violates its own code of conduct. Time and time again, following allegations by labor rights watchdogs and the media, Apple claims to be conducting on-site investigations, interviews of workers, and audits of factories, and subsequently denies the majority of the findings. After China Labor Watch released a report in 2019 on the use of contract labor, excessive overtime, and unpaid overtime wages, among a string of other violations, Apple stated it had “looked into the claims… and most of the allegations are false.”

If Apple relies on audits at the factories to determine the state of working conditions, then surely these audits are highly questionable; revelations of forced labor have even surfaced. Given the profits Apple makes, it has the capacity for greater oversight. If Apple, one of the most profitable companies in the world, is unable to protect the rights of workers in its supply chain, then one should seriously question the working conditions of smaller companies.

Media exposés at first were integral to shedding light on rights violations at Foxconn and raising awareness. But this has not been enough. Apple’s rights violations have been widely reported over the years, and despite some improvements, these have clearly been limited. Negative media reporting takes a very targeted approach. Where Apple acknowledges that conditions have fallen short of its standards, the company merely addresses the factory in question, rather than making wholesale improvements in the supply chain.

In concluding, the authors look to the future of Foxconn workers and the many constraints they face in improving their lives on the production line. Those include the government’s lax enforcement of laws, its encouragement of the employment of interns, its strict control of unions, and its crushing of labor-rights NGOs. Especially as the company expands across the world, the authors suggest that to make fundamental improvements to workers' lives, a broader movement that connects workers worldwide is indispensable.

LEAVING CHINA?

With escalating tensions between the U.S. and China, Apple has been shifting its production bases to other countries, and this has been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which reveals the risks of over-relying on one country for production. Other companies are expected to follow suit.

Workers should avoid being caught in the crossfire of the U.S.-China conflict as nationalist sentiments rise in both countries. With the potential relocation of factories, terrible working conditions and workers' struggles against them will only be replicated elsewhere. I echo the authors’ call for “transnational activism in opposition to the oppression of labor wherever it is found.”

Elaine Lu is a labor activist and researcher.