The Biggest Bargaining Mistake Unions Are Making in 2025

These signs highlight the affordability crisis that workers are facing because inflation has been so high. The biggest mistake that unions are making in contract bargaining these days is not fully counting inflation. Photo: UE Local 150

When unions get ready for bargaining, we tend to look at the wage scale in our existing contract and think something like, “Let’s open with a proposal for a 5 percent raise every year, and maybe eventually we’ll settle at 3.75 percent.”

This type of proposal was made out of habit when inflation was around 2 percent. While that may seem like a logical way to approach negotiations, you’re making a big mistake if you don’t take a closer look at the numbers.

The error that many bargaining teams make is not reviewing the cost of living each of the previous five years. Because of extreme inflation during the last five years, minimum increases of as much as 10 percent may be needed to restore purchasing power.

The cost of living shot up 6.1 percent from June 2020 to June 2021, followed by a 9.8 percent increase over the next year. That means that if you’re starting from your current wage scale, you may be starting from salaries with much less purchasing power than the last time your contract was negotiated.

I conducted an informal survey of more than 30 Teamsters collective bargaining agreements and found that the 2025 wage scale is lower than the “real wage” in 2020 for many of them.

DO THE MATH

Intuitively, we feel we are not doing as well as we did in the past. But is it quantifiable?

Yes—and you can do it yourself, using tools from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Every month, the BLS surveys the cost of over 400 items. The survey includes rent, gas, eggs, shoes, electric bills, and more.

The Bureau provides a shortcut to immediately determine if you are behind:

- Go to bls.gov

- Scroll down the page to CPI Inflation Calculator.

- Enter the start date and start wage you wish to compare. Consider choosing the starting wage from your last contract, or a date five years ago (i.e. September 2020).

If your current scale is less than the Bureau’s calculation, sound the alarm!

For example, say your scale in June 2020 was $30 an hour. The BLS says to have the same purchasing power as $30 in 2020, you would need to be making $37.54 as of June 2025.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

A real-life example: Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Local 1’s contract with Tops Markets in New York’s Adirondack region went into effect in October 2021, near the beginning of the pandemic-era surge in inflation. When the contract expires this October, a journeyman at Tops who started at $18.80 four years ago will be making $20.25. According to the CPI calculator, they would need to be earning $21.96 today to have the same purchasing power as they did at the start of the last contract—meaning the union should be demanding big wage increases in the first year of the contract.

There are likely several different classifications of workers covered by your contract, working under various wage scales. You can check each of them, too. Non-union workers can also use this tool to see if their wages have fallen behind.

DEMAND A COLA, TOO

Your research can go back further than five years if you want; the CPI Inflation Calculator tool goes all the way back to 2000. You might want to look at that data if your employer has forced concessions on its workforce, including lower-paid tiers, or if your contracts have included lump-sum payments instead of increases to the wage rate.

Bargaining teams should also propose a well-developed cost-of-living adjustment. If nothing else, it provides added leverage for an increase in the basic wage if it’s rejected by the employer.

Obviously, winning big wage increases to make up for any lost purchasing power isn’t just a matter of presenting management with evidence they’re shortchanging you. You’ll need to prepare for a serious contract campaign, backed by a real threat to strike. Your union may also need to commit to organizing the unorganized sections of your industry, to have the power to set wages.

But don’t lowball yourselves with your proposal, or what you’re willing to settle for. Things have gotten expensive—and negotiations need to reflect that.

A DEEPER DIVE

For more detailed data, stay on the BLS homepage, and click SUBJECTS. In the first column click Consumer Price Index. On the next page, click CPI Data, and then click Databases in the drop down menu. Open the green box: Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (Current Series) One Screen. Open and enter the required information.

Or if that’s too much work, just click here.

- For “Select an Area,” select U.S. city average, or your metro region, if you prefer.

- For “Select one or more Items,” choose All Items.

- For “Select Seasonal Adjustment,” remove the check mark by Seasonally Adjusted. (Keep things simple and use the Non-seasonally adjusted figures.)

- Left click “Get Data.”

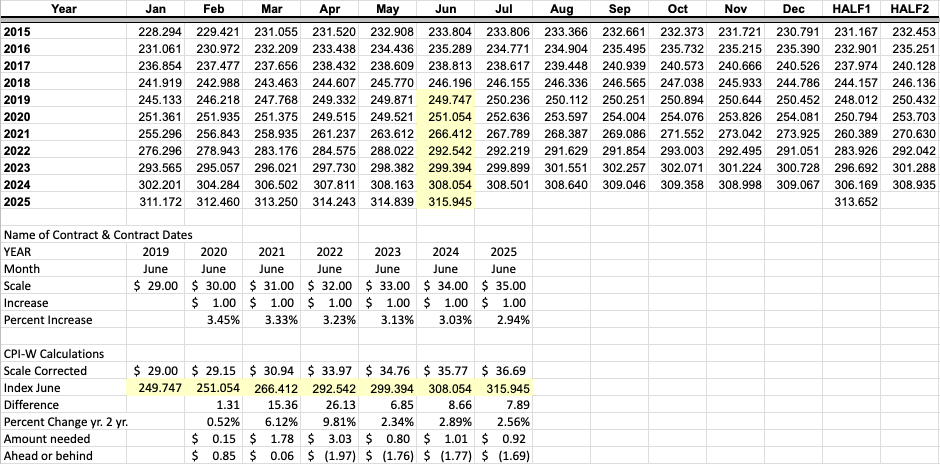

Open Excel or Google Sheets and create a table like the one below which compares the five-year bargaining record to the Consumer Price Index.

In the example above, you can see that bargaining with an increase of $1.00 each year was good from 2019 to 2020, and slightly positive from 2020 to 2021. But each year after that the contract resulted in a loss of purchasing power.

In this contract, starting from a wage of $29 in 2019, you would need a wage proposal that starts at $36.69 just for workers to break even with what they were making six years ago.

Richard de Vries recently retired after 30 years as a union representative with Teamsters Local 705 in Chicago. Contact him at richardjdevries1852[at]outlook[dot]com. Thanks to Seán McGovern for additional research.