How West Virginia Activists Organized a Solidarity Fund for the Uprising

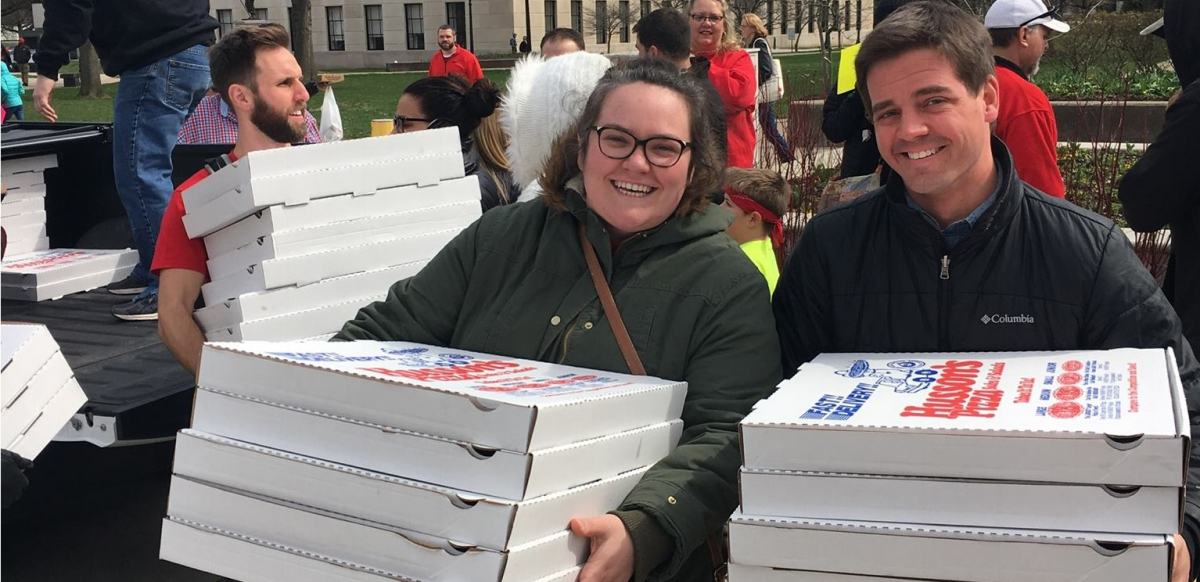

West Virginia teachers received hundreds of pizzas from supporters. A strike solidarity fund set up by community organizers also raised over $300,000. Credit: Eric Blanc

Strikes are won by workers—often with a little help from their friends.

During their two-week strike, West Virginia’s salaried classroom teachers still got paid, because superintendents closed schools. The days missed were treated like snow days to be made up later. But workers paid by the hour or day—such as substitute teachers, teaching aides, bus drivers, and cafeteria workers—weren’t getting paychecks. Few had much savings to fall back on.

“These folks were on the picket line and supporting the strike, but stood to not be able to pay their rent or heating bill,” said Stephen Smith of the West Virginia Working Families Party.

So he and a few other local activists set up an online appeal to help cover lost wages. Seven thousand people from all over the country gave an average of $48 apiece, totaling $332,945.

Here are some lessons from their experience:

HAVE A UNION STRIKE FUND

Solidarity fundraising should supplement, not substitute for, a union’s own strike fund, set aside gradually as a portion of members’ dues.

Every union should have a strike fund. West Virginia’s teacher and school employee unions didn’t. They were lucky—their strike caught the national imagination, and donations poured in. That won’t usually be true.

Even in West Virginia, organizers were concerned that superintendents might break ranks and reopen schools, meaning that teachers who stayed out would lose pay. If that had happened, the donations wouldn’t have been nearly enough.

START EARLY

Strikes are chaotic, so fundraising should start beforehand if possible. In West Virginia, the first conversation about setting up the fund came two days into the strike.

Many tasks can be accomplished ahead of time: creating a website, creating an online application for assistance, testing that donations are being deposited in the bank account, and crafting a media message.

HAVE A HOST ORGANIZATION

Having someone personally responsible for the money can get messy. “If you raise a lot of money, like we did, it would really screw up an individual’s taxes,” says organizer Cathy Kunkel.

Instead, you can ask a trusted local nonprofit to be the “fiscal sponsor” for your solidarity fund. “The organization should set up a separate bank account for the fund—to easily track it, and in case they get audited,” Kunkel says.

“Folks in other states might find, with more planning ahead of time, that it could run through a union,” says Smith.

Since multiple unions compete for membership among West Virginia teachers and school employees, organizers decided to keep the fund independent of the unions. RiseUp West Virginia, a community organization that Kunkel founded after the 2016 elections, acted as the host.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Still, they sent regular updates to union leaders, so that unions could attest to the fund’s legitimacy and direct members to apply for assistance.

ASSEMBLE A STRONG TEAM

It helps to recruit people who’ve worked together before. “We had pretty close bonds and trust to begin with,” says Kunkel. “It would have been more difficult if we were five strangers.”

Assign a specific role to each volunteer—like verifying applications, maintaining the database, or handling communications.

It also helps to have insiders involved. The fund organizers weren’t strikers themselves, so they recruited an active teacher and a former school support worker. These volunteers explained education and union terms to the other committee members, and verified information in the applications for funding.

BE TRANSPARENT

The webpage for donations laid out what would be funded, named all the strike fund organizers, and encouraged direct contact. Organizers posted regular updates about the donations received and the number and amount of requests that were granted.

The site outlined a clear process for striking workers to apply for help. It also explained what would happen with any leftover funds and how administrative costs were being covered. (In this case there were none, since volunteers donated their labor and picked up the tab for materials.)

Still, be prepared for criticism. “Even with the level of transparency we had, there were many people online who were critical and skeptical that the fund was real,” said Smith. “That is okay and you just have to meet it with openness.”

USE NATIONAL NETWORKS

The webpage went viral after the Working Families Party and Democratic Socialists of America shared it through their national networks and on social media. Press attention from USA Today and Newsweek also helped.

PRIORITIZE REQUESTS

As more donations came in, the organizers granted more requests. The more strikers received help, the more they told others about it. Eventually the fund received more requests than it could fill.

But not all needs are equal and you may not know how long the strike will last. The lesson: “You shouldn’t just fill requests as they come in, but should create a list of priorities,” says Kunkel.

“It’s important to get some checks out so people know that the fund is legitimate,” she says, “but the focus should be on the greatest need in the beginning, because you can always come back and fund others down the road.”

Here is the priority list that the group agreed on (from highest to lowest):

- Low-income people losing pay

- Higher-income people losing pay

- People with a demonstrated emergency (typically medical or housing-related)

- Strike-related service projects (like food pantries and childcare)

- Strike organizing activity, like picket signs and travel expenses

YOU WILL WORK HARD

“You cannot underestimate the amount of work this takes,” says Smith. “There were hundreds of volunteer hours over the course of just a few days. We worked very late into the night, including an all-day session.”

Questions? Contact fund organizers Cathy Kunkel, cathykunkel[at]gmail[dot]com, and Stephen Smith, wvstephennoblesmith[at]gmail[dot]com.