How to Spread the General Strike Beyond the Twin Cities

Unions and community groups led a massive protest against ICE on January 23 in Minnesota. Nearly 100,000 people marched in downtown Minneapolis. Photo: Brad Sigal.

On January 23, Minnesota unions and community organizations seized the public imagination with “a Day of Truth and Freedom,” an economic blackout that drew perhaps 100,000 marchers to downtown Minneapolis.

The Twin Cities have been under siege from federal agents since December. Minnesotans have formed dense networks from the bottom up to patrol neighborhoods, feed the hungry, and train everyday people to scout for rampaging Border Patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents hunting for their immigrant and citizen neighbors. They upped the ante by organizing a general strike with political demands to oust ICE out of their state, deny it any additional federal funding, and hold legally accountable the officer who killed Renee Good.

A new poll conducted by the firm Blue Rose Research shows that almost a quarter of Minnesotans say they took part in what organizers called “a day of no work, no shopping, no school.” A thousand demonstrators protested at the airport alongside 100 clergy, while a sea of tens of thousands marched downtown, and 1,000 businesses closed for the day.

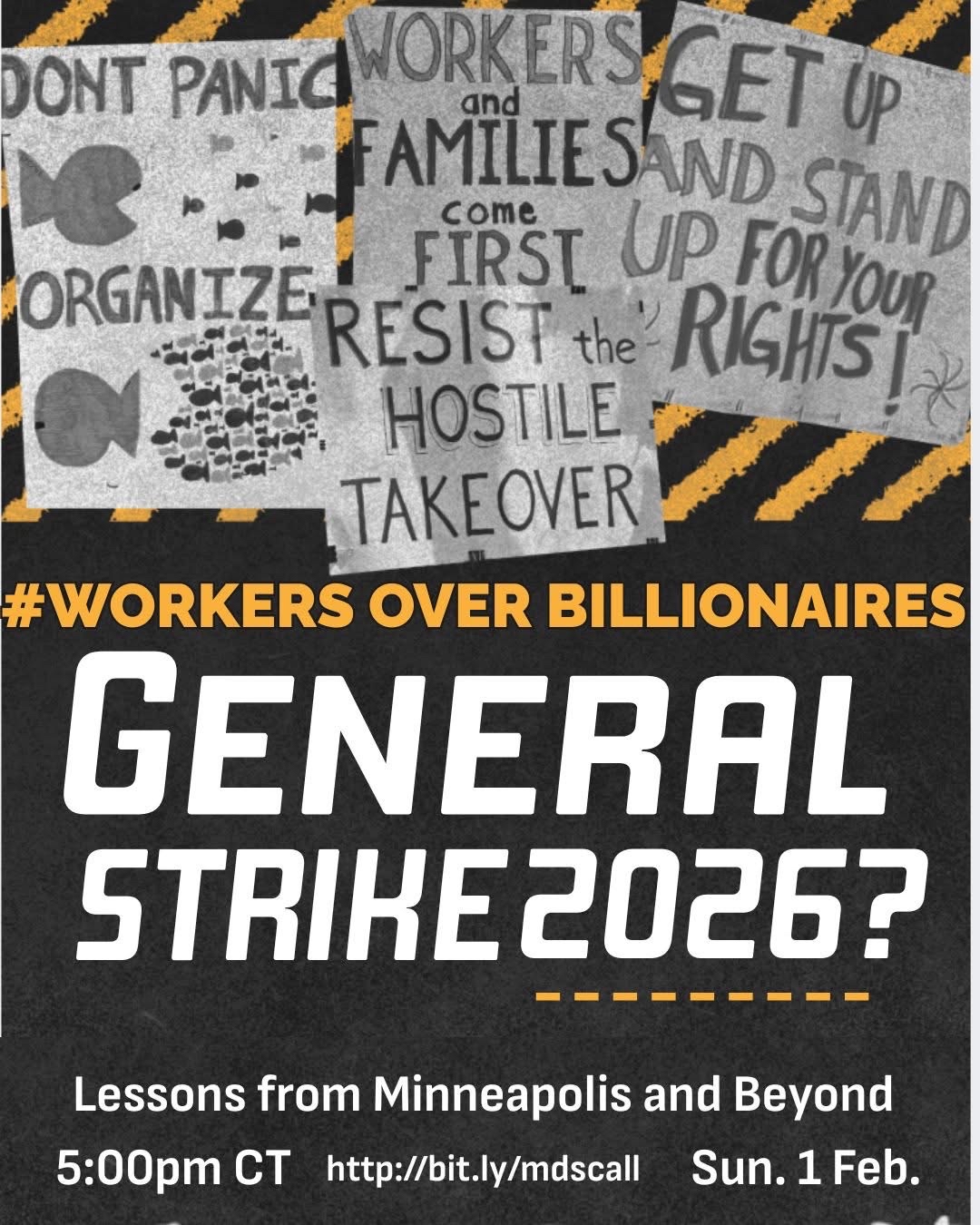

What happened in the Twin Cities that made it possible for organizations to pull off such a successful strike? And what can be done to make such actions succeed in other parts of the country—perhaps in time for the next No Kings Day protests on March 28, and then May Day 2026 as a possible national day of no work, no shopping, and no school?

THE MINNESOTA MODEL

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, when Minnesota was run by anti-worker conservative governors, a group of unions along with faith-based and community organizations began to think about how to work together to build power.

Many of these organizations had a real base and were large enough to want to fight for bigger things, but not so large they thought they could go it alone. If they kept working in their own separate silos, the movements would keep falling behind.

This collaboration was formalized in 2011 as Minnesotans for a Fair Economy; it later evolved into what people now call the Minnesota Model. That meant leaders and members willing to raise expectations, take risks, and slog through the hard work of forming long-term organizational relationships, or alignment.

RAISE EXPECTATIONS

A coalition won’t hold if groups join only because it is “the right thing to do.” Its members have to see their material interests tied to the success of the alignment. Here’s how SEIU Local 26 President Greg Nammacher summarizes the steps his union had to take to make the alignment work:

First, get your own house in order. Movements’ fundamental power lies in numbers and ability to work together inside an organization, which required good old-fashioned base-building—talking to members and raising expectations for big demands that members want. This was a scary step; raising expectations sets up leaders to have to deliver. Nammacher says, “The job here is to raise expectations and then not suppress them.”

This also required creating a leadership structure to get more members involved, shifting from a service model to an organizing culture. Other unions in the Twin Cities were doing this at the same time. St. Paul Federation of Educators President Leah VanDassor said they went from treating the union as a pop machine where you can get a can of Coke to treating it like a gym membership: You have to work to get something out of it.

Once they had more members who were excited about big demands, they escalated with small actions, member surveys, and big meetings to reinforce the demands. Unions opened up bargaining to engage more members. And they aligned contracts within their local to gain more power.

GOVERNING BLOC

Second, fight the enemy. That meant knowing who were the big players who set the rules, who were the natural allies who had the same enemy, and what were the links between these different organizations’ demands. A successful campaign needs to identify the target, learn its vulnerabilities, build relationships with others who can help leverage power, and create a crisis for the target.

Third, align for long-term governing power. Often our individual organizations get stuck at the level of corporate or issue campaigns. That can establish coalitions and transactional relationships (if you support us on X, we’ll support you on Y), but we must develop deeper alignment. Who are your long-term allies, who need to be at the table with you to eventually run your city, state, or industry? How can you coalesce the grouping of forces that could be a new governing bloc?

This includes developing demands that are too big for your group alone to win. Maybe you can win a strike or wage increase on your own, but these demands are about who sets the rules under which we operate. Some of these are what have been called Bargaining for the Common Good demands, and some are long-term structural changes that are needed to transform power and wealth in society.

In Minnesota the alignment work hasn’t been easy; there were both internal tensions and conflicts between organizations. But the organizations stayed committed and developed a shared calendar of fights, a shared power analysis, and shared training and capacity development to emphasize member engagement, political education, and leadership development (rather than letting the alignment rest on relationships between top leaders).

The escalation has now accelerated in the Twin Cities, but it must also reach beyond it.

GENERAL STRIKES

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

We hear calls for a general strike all the time, but such strikes are rare in the U.S. They are not, however, unknown. Notable examples include the massive exodus of enslaved people from plantations during the Civil War (in what W.E.B. Du Bois called “the great strike”) and the famed citywide general strikes in Seattle (1919), San Francisco and Minneapolis (1934), and Oakland (1946).

More recently, the 2006 immigrant rights protests resulted in massive walkouts that forced employers to shut down for a day.

The idea gained new traction when the United Auto Workers, after its powerful Stand-Up Strike in 2023, called on as many unions as possible to align their contract expirations around May 1, 2028, to create a nationwide compression point and leverage maximum power for working people. The UAW is particularly focused on winning gains in health care, pensions, and a shorter workday.

But we won’t be able to build a true general strike in 2028 without organizing now.

MAY DAY STRONG

The Minnesota Model and the UAW’s call for a season of strikes in 2028 were part of what inspired the Chicago Teachers Union to build the May Day Strong coalition, a national network of labor and community organizations, in 2025.

May Day Strong has worked to build alliances in cities around the country, aligning workplace and community organizing to shared targets, demands, and calendars.

May Day Strong is organizing Solidarity Schools in cities around the country. (Labor Notes also has resources for people to self-organize fightback schools.) You can attend one with your organization to learn and practice skills including identifying leaders, talking to co-workers and neighbors, and taking escalating action. The schools are also a space to learn about the attacks on our people and our economy, build alignments for the long term, and discuss strategy.

BUILDING MUSCLE FOR DISRUPTION

Our task now is to build up our muscles for non-cooperation. This could take different forms, but needs to be more than just another rally or march. We need to see May 1, 2026, as a place to test our muscles; Labor Day will be another. And a real test may come this fall, if the Trump administration interferes with the midterm elections.

A strike is one of the best forms of muscle we have, because employers hold sway over the state. By targeting employers who support the Trump regime, workers can use their disruptive power to put economic pressure on the bosses, generating a crisis that can force them to defect.

But pulling off any strike is hard, let alone a general one. Most collective bargaining agreements have no-strike clauses, which means that going on strike while the contract is in effect could result in serious penalties. Public sector unions in many states are prohibited from ever striking. So, many workers would not only lose wages in a strike—they’d also risk being disciplined or fired.

Despite the risks, strikes happen! Even among public sector workers, such as in the 2018 wave of teachers striking. But strikes take planning. Workers need to know that if they take big risks, other people have their back through collective efforts to raise funds, figure out childcare and meals, and build a base to ensure reliable commitments.

The Minneapolis Regional Labor Federation is backing an eviction moratorium. Its nonprofit arm Working Partnerships has established a legal fund to support illegally detained workers. The more unions and community organizations work together, the greater their power.

‘MOMENTS OF THE WHIRLWIND’

The Minneapolis unions did not call for strikes on January 23. But with 36 members of UNITE HERE Local 17 and SEIU Local 26 abducted by ICE since last year, and many workers skipping work for fear they’d be detained, pressure was boiling over. Unions seized the crisis and turned it into an opportunity to support workers’ self-organizing.

Some workers told their union leaders they wouldn’t show up for work. Some called out sick or used a mental health day. The extreme cold shut down the schools, making it a non-workday for all educators.

This experience shows how strong base-building and internal cohesion, and leaders who let members take initiative, can help workers self-organize to lead work slow-downs, sit-ins, walkouts, and other forms of direct action, including strikes. The secret sauce is melding worker self-activity with organization.

Minnesotans had 15 years to build their alignment. We can learn from their experience, but we need to learn quickly. Mark and Paul Engler talk about “moments of the whirlwind.” Suddenly, things that seemed impossible are possible. In a whirlwind moment, our time seems to expand and our focus intensifies, opening up new possibilities. We have no choice but to scale up nationwide.

Stephanie Luce is a professor at the School for Labor and Urban Studies, City University of New York, and a member of the Professional Staff Congress-CUNY/AFT.

![Eight people hold printed signs, many in the yellow/purple SEIU style: "AB 715 = genocide censorship." "Fight back my ass!" "Opposed AB 715: CFA, CFT, ACLU, CTA, CNA... [but not] SEIU." "SEIU CA: Selective + politically safe. Fight back!" "You can't be neutral on a moving train." "When we fight we win! When we're neutral we lose!" Big white signs with black & red letters: "AB 715 censors education on Palestine." "What's next? Censoring education on: Slavery, Queer/Ethnic Studies, Japanese Internment?"](https://labornotes.org/sites/default/files/styles/related_crop/public/main/blogposts/image%20%2818%29.png?itok=rd_RfGjf)