Popular Uprising Backs Striking Teachers in Southern Mexico

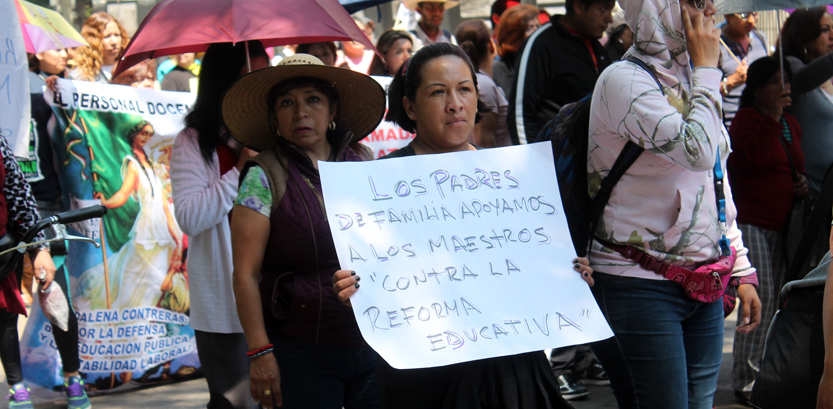

The fight for teachers’ rights has blossomed into a movement against education privatization. This sign at a July 6 march says, "We parents support the teachers against the education reform." Photo: Valeria Méndez (CC BY-ND 2.0)

In Chiapas, Mexico, what started as a fight for teachers union power has exploded into a popular movement against the privatization of public education and the entire public sector.

Fifty thousand teachers, students, parents, and small-business owners marched at sunset July 11 through the streets of Tuxtla Gutiérrez, the capital city of Chiapas—in just one of at least 10 protests across five states.

Meanwhile an hour east, in the city of San Cristóbal de las Casas, parents, students, social justice organizations, and members of civil society were gathering for the 15th night of their highway blockade.

The protests came as representatives of the CNTE, the dissident caucus in the teachers union, met with federal representatives in Mexico City for their third dialogue on the controversial education reform.

The teachers have been fighting this reform since 2012, when the Mexican Congress passed the measure. It’s being imposed gradually, region by region. But in the last few months, as the reform has encroached on the more militant southern states, the fight for teachers’ rights has attracted more allies and blossomed into a movement against education privatization.

“We’re not guerrillas, we’re citizens raising our voices to tell the government that we don’t want this law,” said Amanda del Rosario Morena Gutiérrez, regional president of the parents organization in Los Altos, Chiapas. “This fight is everybody’s now—all poor people.”

SCHOOL TAKEOVERS, HIGHWAY BLOCKADES

Since launching their strike May 15, teachers across Chiapas, Oaxaca, Guerrero, Michoacán, and Mexico City have held marches almost daily, set up permanent encampments in city centers, seized tollbooths in daily highway blockades, and even blocked trains.

When the teachers first went on strike, many principals threatened to fire them if they did not return to work. But the parents of their students occupied the school buildings, saying they wouldn’t allow the teachers to work, so the principals could not blame them.

After the first month of the strike, on June 19, police killed at least 12 protesting teachers and students and wounded over 100 in Oaxaca.

When the government accepted no responsibility and continued to refuse to negotiate, the movement escalated.

At dawn on June 27, teachers, parent organizations, students, and civil society groups throughout Chiapas (which neighbors Oaxaca) built camps thousands strong, on 12 major highways and four international bridges linking Mexico and Guatemala. Their blockades joined the dozens in Oaxaca, seven in Guerrero, and one in Michoacán, effectively bringing all of southern Mexico to a standstill.

Highway blockades have been a common tactic throughout the teacher struggle, but this was the first time that the blockades were built to stay indefinitely.

GAS AND INTERNET SQUEEZED

The government responded immediately—but not with physical force this time, as it was already facing a wave of allegations of human rights abuses after the massacre in Oaxaca.

Instead the government launched a multi-tiered campaign aimed at turning civil society against the teachers and sent a steady flow of infiltrators and instigators in the blockades themselves.

The same day the blockade went up in San Cristóbal, the Internet virtually stopped working in the whole city. Since social media has been the movement’s main tool for communicating and organizing, it’s widely believed that the government slowed the connection.

The following day, gas stations throughout the city received government instructions to stop selling gas. The lines of cars clamoring to fill their tanks stretched for miles. Mainstream media played up panic about shortages and the crash of the tourism industry, and tried to turn transportation workers and business owners against the teachers.

It didn’t work. Instead, people across San Cristóbal and Chiapas rallied around the teachers.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Small business owners formed their own delegations and joined the marches. People brought supplies and arrived at the blockade with coffee and bread for those guarding the barricades at all hours of the night.

Groups of retirees set up their camps on the highway. Parents went door to door, organizing their schools and neighborhoods.

Taxi drivers put signs in their windows declaring their support for the teachers. Every driver I spoke to blamed the government for the gas shortages that are putting their livelihoods at risk.

“We make very little money in our profession,” said Alberto, a driver who took me to the blockade. (He didn’t want to give his last name.) “If education is privatized, we won’t be able to pay to send our children to school. If the government doesn’t reject the reforms, all 2,000 drivers in the city are joining the blockade with our taxis.”

HIGH-STAKES EVALUATIONS

The teachers call it “the poorly named education reform.” Despite government claims that it’s meant to improve education, they say its real purpose is to undermine their union and degrade their rights.

The reform would impose a standardized evaluation in the form of a test that would determine hiring and firing.

Many teachers point to the extreme inequality between urban and rural schools. “They tell us that we have to perform equally, but how can we be equal in a computer exam when we don’t have a computer or even a classroom to teach in?” said Reyna Gómez, a teacher in an indigenous community in rural Chiapas. Instead of addressing this inequality, the new evaluation system pins the blame on teachers.

The reform would also replace teaching positions with short-term contract positions—which the CNTE says would mean hundreds of thousands of layoffs.

“Since the [Mexican] Revolution, the schools are where the people gain their consciousness,” Gómez said. “They want to eliminate real learning, so that people aren’t aware of their conditions. And with the reforms, anyone teaching material that the government doesn’t like can be fired, just like that.”

Beyond destroying labor rights, the CNTE contends, the reform advances the government’s plan to privatize the entire education system.

The education reform was introduced as part of a package of 11 structural adjustments—retribution for unpaid loans to the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—created by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the World Bank, aimed at opening public services such as health and energy to private investment.

Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto pushed the reforms through Congress immediately upon taking office, in his first steps toward what he calls “modernization” but critics call neoliberalism.

HARD-WON PROGRESS

In the July 11 dialogue, Minister of the Interior Osorio Chong and CNTE leaders agreed to move into a phase of negotiation with three sections—political, educational, and social—corresponding to the principle demands of the movement, which are:

- Immediately suspend the reforms.

- Initiate a social process of educational transformation and the development of a new national model of education.

- Resolve the consequences of the reform, which include teachers being fired, taken as political prisoners, and even murdered.

This hard-earned progress comes just two weeks after Peña Nieto told reporters in Quebec, “What the government is not willing to do is to negotiate the law.”

Though they have now entered negotiations, the CNTE is hesitant to recognize this as a positive step, warning that it could be a strategy to extend empty dialogues and wear down the resistance.

The ongoing blockade in San Cristóbal has become a living example of the popular labor movement that’s spreading across Mexico, with 19 states now united in the fight against the reforms. By standing with the teachers union, ordinary people are refusing to let the government scapegoat teachers or privatize education.

They are revealing what’s actually at stake in the education reform—and in the privatization that the World Bank is pushing in other sectors, too—the lives and livelihoods of poor and working people.