As Cargo Chains Grow, So Does Workers’ Leverage

Editor’s Note: Labor Notes is pleased to announce the release of The Cargo Chain — a joint project with the Longshore Workers’ Coalition and the Center for Urban Pedagogy. This pamphlet examines the network of workers and machines that move goods across the globe, the potential power this system creates for labor, and what companies are doing to undermine this power. Order this pamphlet online

Truck drivers at HUDD Distribution, a division of shipping giant A.P. Moller-Maersk, walked off the job December 17 at the company’s facilities in South Gate and Mira Loma, California. The drivers, primarily Latino immigrants known as troqueros, shuttle goods between the massive port of Los Angeles/Long Beach and the company’s inland warehouses.

Drivers were protesting a company move to unilaterally modify their contracts, cutting wages in tandem with reducing freight insurance. Port truckers, while often tied to a single company, are classified as independent contractors rather than employees, making it impossible to form a union under existing labor law.

HUDD drivers stayed off the job for almost two weeks, but quickly found themselves in the crosshairs. Within days the terminal operator APM, another division of A.P. Moller-Maersk, had contracted with a different trucking company to move the idle shipping containers inland. Then on December 28 the drivers’ bid for solidarity from local longshore workers was quashed when an arbitrator ordered dockworkers back to work just hours after they refused to cross the truckers’ picket line.

GLOBAL NETWORK

The situation for the troqueros is just the latest example of workers squeezed by the titans of the global economy. A.P. Moller-Maersk is the world’s largest shipper, moving close to 15 percent of cargo in and out of the United States. A majority of the containers HUDD transports are for Wal-Mart, the world’s largest retailer.

The Cargo Chain explores the ever-expanding network of ship hands, longshore workers, truck drivers, railroad operators, and warehouse workers that make the global marketplace possible. To the average consumer, these workers are practically invisible, but they are at the crossroads of today’s economy, moving billions of dollars of goods daily.

And their importance is growing, judging by the surge of goods moving in and out of the country. Just one example is the number of containers—the 40-foot steel boxes that hold everything from flat-panel televisions to scrap metal—that enter and leave the United States, a figure that has doubled in the past 10 years.

JUST-IN-TIME LEVERAGE

This growth is the result of a strategy by retailers like Wal-Mart, Home Depot, and Target to create a seamless supply chain, slashing inventories and delivering goods “just in time” to the customer. Ships, intermodal yards, and trucks have been transformed into mobile warehouses.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

While adding to the corporate bottom line, this has put tremendous pressure on an already over-stretched transportation network, increasing the risk of disruption—and the costs that go with it—as well as amplifying the potential power of workers.

One recent flash point was last year’s strike by conductors at Canadian National, Canada’s largest rail carrier. The two-week walkout cut container traffic in half at the Port of Vancouver and caused major disruptions across Canada’s grain, forest products, chemical, plastics, gas, and auto industries. The stakes were so high that a week into the strike federal legislators ratified back-to-work legislation, strengthening the company’s hand in bargaining.

EMPLOYERS ON THE MOVE

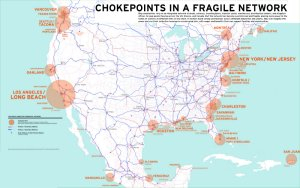

Companies also recognize the potential power for workers in the cargo chain, and are taking steps today to protect tomorrow’s profit. A key goal is to expand shipping options so cargo isn’t bottlenecked by a strike, storm, or natural disaster. As the HUDD drivers quickly discovered, shippers already can effectively pit non-union short-haul drivers against one another.

But employers are also searching for more ways to route cargo through ports or overland, a move that will temper the power of unionized workers on the docks, the railroads, and the highways. APM is building a new $250 million terminal in Mobile, Alabama, at the same time that terminals in Houston, Norfolk, Virginia, and Savannah, Georgia, are being greatly expanded.

Railroad companies are working with the Department of Transportation to create massive rail yards, renovate track, and raise overpasses to make way for rail cars that carry two containers stacked on top of each other. Norfolk Southern now has a direct line from the Virginia ports to Chicago and the Midwest since overpasses were raised to make way for “double stack” rail cars.

Companies are also using new technology to cut jobs and shift control of the work from people onto machines. At a newly expanded terminal in Norfolk, for example, yard cranes run without an operator, using GPS technology, cameras, and computers. Rubber-tire gantry and rail-mounted gantry cranes can stack containers seven high and six wide, delivering containers to trucks or rail cars. Six cranes can be operated at once from a computer booth inside the terminal.

UNDERSCORING SOLIDARITY

These developments only deepen the need for solidarity among workers in the cargo chain, union and non-union alike.

One key test will be the fight to defend standards on the docks at the bargaining table. In July the contract for West Coast longshore workers expires, and the memory of the 10-day employer lockout in 2002 is lingering over current talks. East Coast longshore workers face an equally important contract deadline in 2010, which will either reverse or reinforce the two-tier wage system put in place during the last round of negotiations.

An even more daunting question is whether unionized workers in the freight network will be able to harness their power to organize non-union workers like the HUDD troqueros.

You must log in or register to post a comment.