In this time of emergency, organizing that might have taken months in the past now needs to happen in a matter of days.

Workers’ lives are increasingly in our own hands. We cannot rely on employers to protect us, nor can we count on OSHA or the National Labor Relations Board to enforce any of our rights. The only winning formula is collective action that forces an immediate response.

Below we lay out some of your legal rights—so you can make sure your employer knows that you know. We lay out the most effective ways of protecting workers—and it's way beyond face masks. Finally, we give some tips on how to organize. But fast.

What Should Employers Be Doing to Protect Workers?

Workers at higher risk of work-related COVID-19 infection include those in health care; critical infrastructure (police, fire, garbage collection, transportation, community care); essential community services (grocery, pharmacy, take-out food, warehousing and delivery); and workplaces where six-foot distancing has not been instituted, that lack adequate hand-washing facilities or ability to frequently wash hands or use hand sanitizer, or that lack disinfecting with proper cleaning materials and procedures.

Remember that possibly 25 percent of those who are infected have no fever and show no symptoms—so we don’t know who could infect us. However, there are ways that all employers can minimize the risk.

This is a long article. Look for the sections that pertain to your workplace and situation.

Work-from-Home Options

Consider a campaign to create or expand this option, which is safer for workers.

Non-essential Workplaces

See the Resources section below for information on continuation of pay or unemployment benefits, and paid health care benefits. Benefits from recent legislation—Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act—may apply.

If your workplace is not an “essential” business or service and should be shut down (but has not been), consider a campaign to get it shuttered for the duration of this crisis and ensure that workers get pay or unemployment benefits, and health insurance.

Workplaces that Continue to Operate

If your workplace is essential during this pandemic, employers need to protect those who remain in the workplace (see below) as well as to take care of those who are not able to work because they are in a “high risk” category (older workers, those with weakened immune systems, those with underlying conditions such as heart disease, lung disease, diabetes); those who are experiencing symptoms, illness, or quarantine; and those taking care of ill or quarantined family members or children not in school.

Assistance to those unable to work would include expanded and paid sick leave and family leave, continuation (or initiation) of paid health insurance, and continuation of seniority. Again, the FFCRA and the CARES Act may apply.

Protections for Workers Who Remain in Workplaces

- Infectious Disease Preparedness, Response and Control Plan: All employers should work with the union or workforce on developing and implementing an Infectious Disease Preparedness, Response and Control Plan that is specific to that workplace, identifies all the areas and activities where exposures to COVID-19 could take place, and develops control measures to eliminate, reduce, and prevent such exposures.

Given the ways in which the virus spreads (through “droplet” or “aerosol” particles generated by sneezing, coughing, talking, or breathing, and by touching something with the virus on it and then touching your mouth, nose or eyes), it is important to review every area, job, and task to identify what protections are needed.

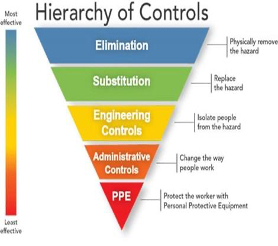

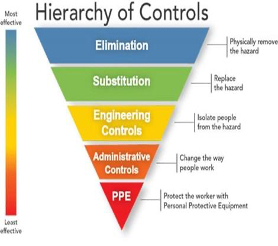

- Hierarchy of Controls: There are a variety of ways to prevent or reduce workers’ exposure to COVID-19, some more effective than others. Employers should be implementing the most effective methods possible, not just the cheapest or most convenient for them. While particular methods will vary based on the type of work and types of exposures, all employers should follow a basic hierarchy, called the Hierarchy of Controls, to select the most protective measures possible. The hierarchy is in the following order:

- Elimination: When a workplace hazard can be entirely eliminated, that is most protective. But until there are controls such as a vaccine and “herd immunity” (where many have survived the virus and are now immune), we expect this virus to be around.

- Substitution: This method removes a hazard and substitutes it with something less or non-hazardous. There is no way to do this with the coronavirus. However, substitution can be used for cleaning chemicals. Some are more effective against this virus and safer than other chemicals that can cause asthma, rashes, and other ill-effects. More info.

- Engineering Controls: The next most protective approach keeps the hazard from coming in contact with workers. In a hospital setting, negative pressure isolation rooms for patients with COVID-19 prevent airborne virus from drifting to other areas where workers and others could get contaminated. Properly sized and placed plexiglass shields (also know as “sneeze guards”) could protect grocery store and pharmacy workers at check-out counters. Automatic doors that open with sensors prevent workers from having to touch a shared surface.

- Administrative Controls: These are workplace policies and procedures that can lessen exposure. Examples include work-from-home options; assuring at least six-foot separation between workers and between workers and others; frequent and proper disinfecting of surfaces; proper hand-washing facilities and expanded times for frequent hand-washing; training on how to properly put on and remove protective equipment such as respirators, masks and gloves (see here); instituting one-person-to-a-vehicle policies; taking temperatures of those entering a workplace.

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): PPE puts equipment directly on the body of workers and is generally the least effective way to protect workers from hazards—but in this crisis PPE is absolutely essential.

Health care workers need powered air purifying respirators, or elastomeric (1/2-facepiece respirators), or disposable N95, N99 or N100 respirators (often used with faceshields) to filter out the virus.

Masks (surgical or cloth, as opposed to respirators) do not filter out the virus, but are thought to reduce the chances that the person wearing the mask will infect others with particles of virus via a cough or sneeze. Wearing surgical or cloth masks does not eliminate the need to keep a distance of at least six feet.

Another example of PPE is disposable gloves, but hand-washing is essential before and after glove use, gloved hands should never touch the face, and hands can become contaminated when gloves are not removed properly (see here.).

Resources

- Some resources for COVID-19 protections, protective policies, and actions:

Take Action! Winning Protections (and Uses/Limitations of Legal Rights)

While a number of health, safety, and labor laws provide worker and union rights in this pandemic, none are going to work quickly enough to get workers the immediate protections they need.

When determining the best strategies to win protection, you may want to submit complaints to government agencies and file charges, to accompany your more direct actions. But given that many government agencies are working remotely, procedures were already notoriously slow, and government action is unreliable, don’t count on these rights alone to win what you need when you need it.

Do take good notes, and prepare and file cases as needed. Consider whether it makes sense to throw the book at the employer—if only for the press release that can recount all the things workers are doing to get safety and justice.

It is always good for the employer to know that you know your legal rights. But do so while organizing collective actions.

Standards and Rights under the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA)

OSHA covers many workers in the private sector nationally and public sector workers in 25 states, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. During the COVID-19 pandemic, OSHA may communicate via phone and email rather than conducting on-site inspections. It is unclear at this time whether and how enforcement is being done.

Below are some relevant OSHA rules and standards, most for “general industry.” For construction and maritime industries, there are other rules and standards, and many are similar.

- General Duty Clause [Section 5(a)(1) of the OSH Act, 29 USC 654(a)(1)]: This section of the Occupational Health and Safety Act requires employers to provide safe and healthful workplaces. The specific language is “Each employer shall furnish to each of his employees employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or likely to cause death or serious physical harm to his employees,” which would include protecting workers from exposure to the coronavirus.

- Regarding rights to use the washroom for frequent hand-washing, an OSHA standard includes workers’ rights to go to the bathroom whenever needed, including to wash hands. (OSHA Sanitation Standard 29 CFR 1910.141)

- For PPE requirements, see OSHA’s Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) standards (29 CFR 1910 Subpart I for General Industry), which cover using gloves, eye and face protection, and respiratory protections

- OSHA’s Respiratory Protection standard (29 CFR 1910.134) must be followed by employers when respirators are necessary. When employers require respirator use, they must implement a comprehensive respiratory protection program that includes requirements for respirator program administration, workplace-specific procedures, respirator selection, worker training, fit testing, medical evaluation, and respirator use, cleaning, maintenance, and repair (see here).

- OSHA includes a weak Right to Refuse Dangerous Work. In order for workers to be protected by this right under OSHA, all of these conditions must be met:

- Where possible, you have asked the employer to eliminate the danger, and the employer failed to do so; and

- You refused to work in "good faith." This means that you must genuinely believe that an imminent danger exists; and

- A reasonable person would agree that there is a real danger of death or serious injury; and

- There isn't enough time, due to the urgency of the hazard, to get it corrected through regular enforcement channels, such as requesting an OSHA inspection.

- OSHA says that workers must take the following steps when using OSHA’s right to refuse work, in order to be legally protected:

- Ask your employer to correct the hazard, or to assign other work;

- Tell your employer that you won't perform the work unless and until the hazard is corrected; and

- Remain at the worksite until ordered to leave by your employer.

- OSHA advises that if your employer retaliates against you for refusing to perform the dangerous work, contact OSHA immediately. Complaints of retaliation must be made to OSHA within 30 days of the alleged reprisal. Call 800-321-OSHA (6742) and ask to be connected to your closest area office. No form is required to file a discrimination complaint, but you must call OSHA.

Many union contracts have stronger “Right to Refuse Dangerous Work” provisions than OSHA does. In addition, a collective work refusal (by two or more workers) can have more power, and also more protection (see Legal Rights for Concerted Action below).

- Whistleblower Protection: Section 11(c) of the OSH Act prohibits employers from retaliating against workers for exercising rights covered by OSHA (such as filing a complaint with OSHA, raising health and safety concerns with employers, or reporting work-related injuries and illnesses).

If workers are discriminated against in any way related to their exercise of these rights, they can file an immediate complaint. This complaint must be filed within 30 days of the “adverse” (discriminatory) action.

- On April 8, 2020 OSHA issued a press release titled, “U.S. Department of Labor Reminds Employers That They Cannot Retaliate Against Workers Reporting Unsafe Conditions During Coronavirus Pandemic.” It stated, “… (OSHA) is reminding employers that it is illegal to retaliate against workers because they report unsafe and unhealthful working conditions during the coronavirus pandemic.

“Acts of retaliation can include terminations, demotions, denials of overtime or promotion, or reductions in pay or hours. Employees have the right to safe and healthy workplaces….Any worker who believes that their employer is retaliating against them for reporting unsafe working conditions should contact OSHA immediately. Workers have the right to file a whistleblower complaint online with OSHA (or 1-800-321-OSHA) if they believe their employer has retaliated against them for exercising their rights under the whistleblower protection laws....”

Note: This is a long process once a whistleblower complaint is filed, and typically has taken a year or two to resolve or dismiss retaliation claims. File complaints as needed, but don’t rely on government action alone to get justice!

Collective Bargaining

- Unions should use relevant contract language (including “right-to-refuse-dangerous-work” provisions which may be stronger than OSHA’s).

- Unions may be able to engage in “instant collective bargaining” over COVID-19 protections—initiated by actions such as petitions, threats of job actions, job actions, alerting the media, group grievances, or informational picketing.

- Demands could include specific protections to prevent transmission of coronavirus, extra paid sick and family leave time, the end to disciplinary absentee policies, temporary closure of workplaces, and more.

Note: workers who are not in unions can legally engage in such “concerted actions” and win protections as well—see next section.

Legal Rights for Collective “Concerted Action”

- Private sector workers with employers covered by the National Labor Relations Act (and some public sector workers where state labor law mirrors provisions of the NLRA) have the legal right to act together to improve pay and working conditions (including health and safety), with or without a union. See here, as well as this useful resource on protected concerted activity for non-union workers from CWA.

- To be protected, two or more workers must join together to speak out or protest. In this case they are protesting employers' lack of protections or problematic actions (or inaction) regarding the coronavirus.

- Examples of NLRB “protected, concerted activity” cases are here.

Remember: Because of the time it takes to file, process, and get results from these types of legal claims and cases, and the uncertain outcome, use these laws and rights only in conjunction with campaigns that build power through solidarity and creative, collective action.

Building Effective and SPEEDY Campaigns

- Research and Information-Gathering: This can be done very quickly and will help you develop the best protective demands. For example, researching the best demands for grocery cashiers will reveal that cloth masks alone are less protective than plexiglass “sneeze guards,” of appropriate height and width, plus wearing a mask. A demand that customers not come into stores, but rather pick up orders outside, may be even more protective.

Use reliable resources, use the internet wisely, conduct surveys, collect first-person accounts, investigate problems, submit information requests to employers (including to identify who has tested positive or has been sent home to quarantine, so that contacts can be identified and screened), research examples of successful actions. See resource links above to assist with research.

- Involve Co-workers: collect everyone’s phone number and email address; set up phone trees and Communication Action Teams; use social media, list-serves, on-line newsletters and internet communication platforms for online meetings. Make sure communication take place in the language(s) and literacy level(s) of your co-workers.

- Develop Demands:Use your research and ideas from co-workers to decide what is needed to fix identified problems. Identify secondary demands if you can’t win your initial demands right away.

- Identify and Exercise Leverage: Make a strategic plan for quickly winning your demands. Think in terms of worker-involving strategies and escalating tactics. Identify and work with allies as you build collective power. The victories needed now for immediate protections must come about quickly, but the power you build in organizing winning campaigns will continue for this and future struggles.

- Coalition Actions: Philadelphia library workers initiated a petition signed by library workers and community members, which won closure of libraries and paid time off for union and non-union library workers.

- Job Actions have provided the leverage to win protections. Across the country, union and non-union workers have planned and held walk-outs, sick-outs, drive-bys, and safety sitdowns and other actions that have increased protections or shut down non-essential workplaces

- A refusal to work by union bus drivers in Detroit won new cleaning procedures, hiring of additional cleaners, bus-loading from the rear of the bus, wipes, and no fare collection, by the next day. Portland, Oregon call-center workers, members of the Industrial Workers of the World, pulled a one-day strike and won paid sick leave. (See https://labornotes.org/coronavirus for many more examples.)

- Be creative: When picketing, stand at least six feet apart; use social media to get media coverage of your actions; use light and color to publicize (“bat lights” can be used at night to project words and images onto buildings); use sound and song to spread messages and show solidarity. Continue amazing social solidarity while physically distancing.

In addition to these job actions, consider this accompanying tactic for more pressure. A local union or a group of workers can write a letter to the local district attorney detailing the lack of protections in their work/place that are putting them at risk for death or serious harm. Include the names of management officials with whom you have communicated and the dates.

Say that if management does not act quickly to implement specific essential protections, the union/group will be back in touch for the possibility of criminal investigation and prosecution regarding this assault and battery with a dangerous weapon.

The letter, signed by the union/group and cc’d to senators, the congressperson, local elected officials, community leaders, and the media, is then given to management with the statement that unless the protections are implemented by a deadline, the letter will go in the mail (or email). See the box for a sample.

SAMPLE LETTER TO A DISTRICT ATTORNEY

Dear [DISTRICT ATTORNEY NAME],

We are employees of X Employer. On [DATE(S)] we spoke to [MANAGEMENT NAMES] about our exposures and potential exposures to COVID-19 and the risk we face of death or serious harm if protections we need, many of them specified in OSHA and CDC guidance, are not implemented. [ADD ANY ADDITIONAL SPECIFIC INFORMATION—including specifics of any COVID-19 cases.]

As of now the protective measures needed have not been implemented, which [IS PROVING/COULD PROVE] deadly for those working here.

We are in immediate fear for our health and lives, and those of our families, and believe we are facing assault and battery with a deadly weapon. If our employer fails to implement adequate protections in the immediate future, we will be in touch with you for the possibility of criminal investigation and prosecution.

Signed,

[union or group of workers]

cc: Senators, Congressperson, mayor, media, etc.

Nancy Lessin is a health and safety educator in Boston.