These days we hear a lot about how Uber and other apps are driving a new “gig economy” where it’s every worker for themself. But Uber drivers in Seattle are banding together to pursue an old-fashioned goal: collective bargaining.

In December their city council backed them up with an unconventional law that asserts the drivers’ bargaining rights and lays out a city-backed process for exercising them.

Daniel Negash Ajema started driving for Uber as a law student, drawn by the flexibility and easy entry. Unlike a cab company, he didn’t have to lease a car and could use his own vehicle.

But right away he started noticing issues. He saw other drivers being let go—or as the company calls it, deactivated—usually because of a low rating from customers.

RATINGS RULE

Uber emails drivers their average ratings every week. Low ratings could be for unfair reasons, Ajema said: “A customer might not like way you look, or think you took a wrong turn, or be intoxicated.”

Nonetheless, he said, drivers with an average below 4.5 out of 5 are at risk. If your numbers doesn’t improve, the app will deactivate you.

“I ran into an older Somali guy at a gas station, and he told me he was just notified that he won’t be working for the company starting tomorrow, because of a lower rating,” Ajema said. “He was really devastated, because he had used up all of his savings to buy a car.”

Another issue was the 20 percent the company skims off of drivers’ fares. After factoring in gas and vehicle expenses, some drivers estimated they were only making $3 an hour.

Uber calls its drivers “partners,” not employees. The traditional approach to winning bargaining rights would require the drivers to convince the National Labor Relations Board that they were employees, while the company would probably argue they were independent contractors.

The Seattle approach sidesteps that question. It sets up a city process to enforce collective bargaining for drivers without asking whether they’re “employees” or not.

OLD-FASHIONED ORGANIZING

Ajema thought that if he gathered enough drivers, the company might fix the problems.

He started by talking to the three or four drivers he knew personally. “Then each of those three to four people went to talk to two to three people, and we had 15 people at the first meeting.”

“I believe if we have hundreds of drivers,” Ajema told them, “I have a good feeling they will listen to us.”

Over three months, the drivers printed flyers, set up a Facebook page, and stood outside Uber’s office recruiting others. They also talked to drivers in busy passenger pick-up zones.

Many Uber drivers in Seattle are East African, from Somalia and Eritrea—an advantage for organizing in a close-knit community, Ajema said. Using their community networks, he and the others brought 200 drivers to a meeting.

The group elected a seven-person steering committee and tasked it to meet with Uber and present the drivers’ concerns.

“My thinking was, this is not one person’s problem. This is all drivers’ problem,” Ajema said. “We’re partners. If we make money, the companies make money. We thought we had the same interests.”

But the drivers were disappointed with Uber’s response. The company said it didn’t want to deal with a group representing other drivers. If drivers had concerns, they should come to Uber individually.

“We thought we hit the wall,” Ajema said. But instead of giving up, he decided to reach out to local unions to see if any would be interested in supporting the drivers. Teamsters Local 117 responded.

IN THE DRIVER’S SEAT

For Local 117, it was an easy decision. The union had already supported Seattle taxi drivers to form the Western Washington Taxicab Operators Association.

The Teamsters helped the drivers form the App-Based Drivers Association. Together the two associations began campaigning to win new rights for both types of drivers.

At the same time, the city council was debating how to handle Uber and other app-based transportation companies’ presence in the city. Uber is now regulated in Seattle, but continues to operate in a legal grey zone in many other cities .

“To engage in a fight to keep out Uber would be pitting worker against worker,” said Leonard Smith, Local 117’s organizing director—and would probably be a losing battle.

Teamsters Local 117 did make recommendations about how the city should regulate app-based companies. But to protect drivers’ rights, the union and the drivers chose to pursue another route: bargaining.

“We could try to lobby for regulation through the political process whenever an issue came up—deactivation, not making enough money, no benefits—or we could get to the point where drivers could sit down and deal with issues through the collective bargaining process,” says Smith.

The App-Based Drivers Association continued the organizing that Ajema had started, connecting with drivers in their own communities.

The association reached out to mosques. Imams would make announcements and allow the drivers to recruit others in mosque parking lots. “We talk to them in restaurants, hookah lounges, wherever they gather,” says Smith.

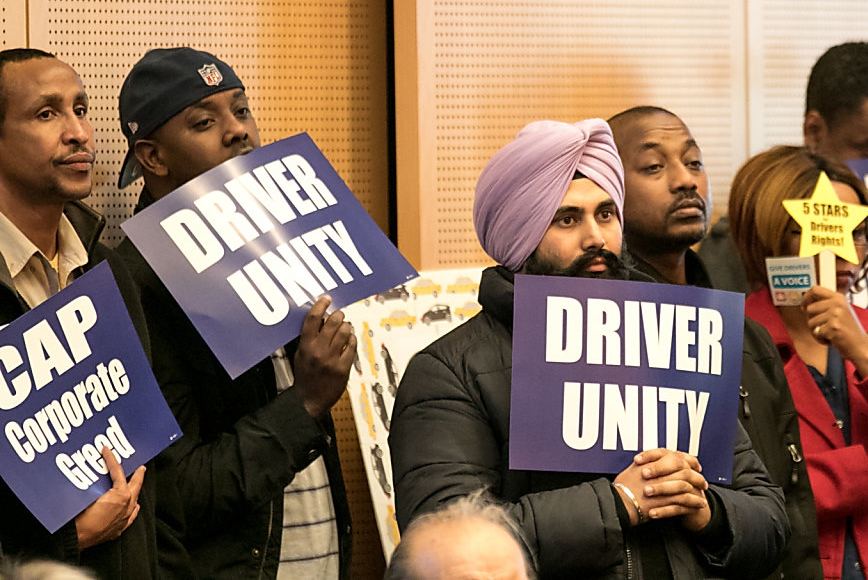

After a year of campaigning—including petitions, actions outside the Uber office, and packing city council meetings—on December 14 the Seattle City Council approved a resolution giving taxi drivers and app-based drivers the right to bargain collectively.

SIGN-UP STEPS

How will it work? Nonprofit organizations such as unions can apply to the city to be Qualified Driver Representative. Once approved, they’re entitled to receive a list of drivers from each company.

An accurate list is crucial for any organizing drive. “At some point I asked them [Uber] to give me that and they laughed at me,” Ajema said. “I thought it would be accessible to public.”

The Qualified Driver Representative then has 120 days to sign up a majority of drivers from a particular company. (Details of this process are still be worked out in implementation rules the city staff will develop.)

The city will review the list. If a majority of drivers have signed up, the organization will have the right to bargain collectively over pay and working conditions. If more than one group gets a majority, the one with the most signups will prevail.

The law covers taxi drivers too. Ajema said the campaign helped to build alliances between the two groups—especially important since many taxi drivers are transitioning to also driving with Uber.

“We know each other. We felt their problems,” he said. “Most of them spent a lot of money to get their medallions, and now they’ve lost the fruit of their investment.”

Will drivers sign up? Ajema is confident this will be the easiest part, even though he expects Uber will try to dissuade them.

“It’s going to be in every driver’s best interest to have the negotiating power to raise the percentage and to improve other issues,” said Ajema. “I don’t see any drawbacks for the drivers.”

STALLED BY SUIT

Legal battles will likely hold up implementation, however, possibly for years.

There’s little or no precedent for what Seattle is trying to do. Uber and a similar company, Lyft, claim the ordinance violates federal labor and antitrust laws. Uber is expected to sue.

But Smith hopes drivers in other cities will build on the Seattle win. Already, California legislators are developing a similar bill statewide.

In October, Uber drivers in a number of cities held a weekend work stoppage demanding better rates. Taxi drivers have been mobilizing too, usually to oppose Uber as the company enters more U.S. cities.

“I don’t think any of us know what this economy is going to look like or where it’s going to go,” says Smith. “In the end, our job is to make sure workers’ voices are heard. When we focus on that, it gets a lot less confusing.”