Salts and Peppers Build a Union at Starbucks

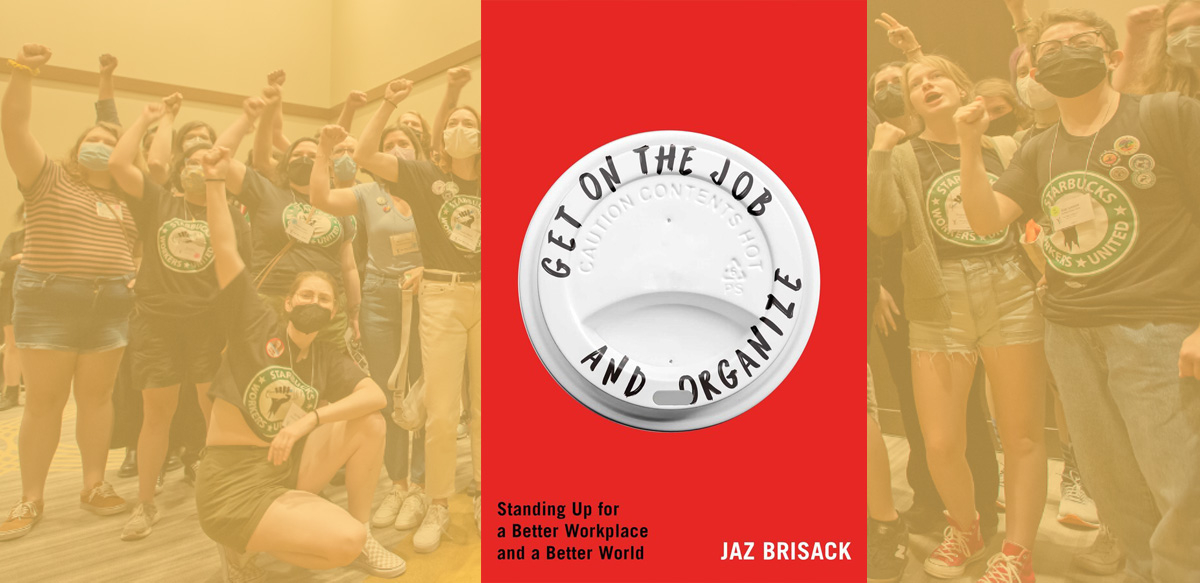

Jaz Brisack’s new book tells the gripping tale of organizing Starbucks in Buffalo, New York, and then across the country. Background photo: Jim West, jimwestphoto.com

Review of Jaz Brisack, Get on the Job and Organize (Atria/One Signal, 2025).

Starbucks Workers United recently celebrated the unionization of their 600th store, disproving reams of conventional wisdom: you can’t organize small shops… you can’t organize high-turnover workplaces… you can’t organize young people.

For a gripping first-person account of how it happened, read Jaz Brisack’s new book Get on the Job and Organize.

Brisack, who uses they/them pronouns, salted at the first Starbucks store to unionize, in Buffalo, New York, but the book starts with their roots in the South and the attempt by the Auto Workers to unionize a big Nissan assembly plant in Canton, Mississippi in 2017.

Brisack was a student at the University of Mississippi and led student support for the Canton workers. Soon they dived directly into the campaign, learning to house call and meeting longtime organizer Richard Bensinger, who would become their mentor.

SALTS

The book is a spirited argument for salting: getting a job with the intent of unionizing a workplace.

Bensinger, Chris Townsend, and Brisack started the Inside Organizer School in 2018 on the theory that while 60 million Americans say they would like a union, most have no idea how to start organizing one.

To release that potential energy, they figured, a revival of the union tradition of salting would be necessary, and salts, in turn, would need to be recruited, trained, and supported.

At Starbucks, it worked just as hoped. In addition to Brisack, ten others, recruited through a vague ad on unionjobs.com, hired in at various Starbucks locations in Buffalo. Starbucks’ policy of allowing workers to pick up shifts at nearby stores allowed the salts to make connections with baristas across the city.

The Workers United Rochester Regional Joint Board, which supported the Starbucks campaign, had previously organized coffee shop workers at Gimme Coffee in Ithaca, and Spot Coffee in Buffalo and Rochester. The plan at Starbucks was to unionize several stores in a condensed region, to raise standards in the area. They overshot that goal by a mile.

POSITIVITY RULES

The Starbucks workers decided they didn’t want to focus too much on bad managers or bad policies, anticipating that their huge employer could flex to dispel those criticisms.

Instead, the campaign built on the love people have for their jobs and their co-workers: a genuine and wholesome argument that the workers were building the union together to make their workplace all that it can be.

This approach landed, partly because jobs at Starbucks, despite erratic scheduling, speed-up, low pay and dumb rules, are not by a long shot the worst in the industry.

In fact, the company’s own rhetoric about fairness and inclusivity and some of its policies, from calling workers “partners,” to college benefits, to trans health coverage, were the very things that encouraged many workers to stay and struggle to make the job better.

PEPPERS

As suspected, dozens of Buffalo Starbucks workers had long been muttering to themselves “Jeez, we need a union.” Suddenly they had someone to talk to and make plans with—they were the “peppers” to complement the salts. Those workers in turn convinced others in their stores, and steeled them for the fight ahead.

The book describes that fight in harrowing and instructive detail: read it if you’re organizing or planning to. Buffalo stores were suddenly crawling with out-of-town managers, including Starbucks president of retail for North America Rossann Williams and other high-level executives, who claimed their presence had nothing to do with the union—they were really just there to refurbish stores and “listen to partners.” Mostly they delivered dark warnings about unionization.

Some of their tactics backfired as mini-tyrants took over from existing managers and instituted petty rules, closed stores for “remodeling” (allowing for endless management propaganda sessions), or shuttered them permanently (in one case after workers spent weeks deep-cleaning and installing new equipment).

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz even made a visit to Buffalo just before ballots were mailed. The company closed all the stores and gathered workers in a downtown hotel ballroom to hear Schultz. The gathering backfired for the company when barista Gianna Reeve stood up to ask Schultz to agree not to union bust. Schultz fled, and video of the incident went viral.

Even with managers breathing down their necks, of the three stores that first filed for elections, the Brisack’s Elmwood Avenue store won outright in December 2021, confirming a mantra of the campaign, “We only have to win one.” They made national news and showed that it could be done.

PARTNERS ON POINT

After that, inquiries rolled in from Starbucks workers across the country, and the union developed a “partner on point” system to help them organize. At first, experienced organizers like Brisack answered the calls, but new worker-leaders who had earned their expertise in recent battle quickly became mentors to baristas around the country. It helped that they all worked for the same company and had intimate knowledge of its workings and anti-union tactics.

Workers tried out new things, including walkouts to address safety and short-staffing. They often met with success as managers scrambled to meet their demands. But as the campaign deepened, managers fired worker-leaders on pretexts, made work life hellacious for others, and closed stores—it shut all three stores in Ithaca, New York, in retaliation. Starbucks racked up a record number of unfair labor practices, clogging labor dockets nationwide.

Camaraderie and sense of united purpose kept people going even when corporate union-busting was at its most disheartening.

When the corporate carrots finally came, they were pretty juicy. A union demand for electronic tipping was instituted, and so were pay raises—except in union stores. This was illegal punishment for unionizing, as judges kept ruling, and probably slowed the campaign. Still, baristas kept calling the union.

SMALL SHOPS, HIGH CHURN

In many jobs, management tactics and automation have isolated workers, making it harder to develop bonds. That’s one upside to organizing in food service, where cooperation is part of the job. But there are downsides, too: workers can quickly cycle through jobs that are both easy to lose and, with unemployment low, easy to find.

Given the churn, the extended and byzantine NLRB election process is tricky to navigate. And that’s even when pro-union workers aren’t fired outright, as at least 200 have been in the course of the campaign.

The Starbucks firing spree started in February 2022 with seven workers in one store in Memphis, Tennessee. Brisack writes that when the Memphis 7 were fired, Workers United should have launched a nationwide boycott to get them rehired. Brisack and Bensinger even laid out detailed plans for a boycott. But union higher-ups opposed it, and worker-organizers debated the danger of turning off potential union members if the boycott significantly reduced traffic in their stores.

Seven months of court maneuvers later, the Memphis 7 did get their jobs back. In the meantime, the one remaining union supporter in the Memphis store organized their replacements and the store voted union. The book is full of astounding stories like this.

BOTTOM UP, TOP DOWN

In taking on big companies, union organizers face a painful dilemma. Brisack argues that it is when members have maximal say that shop floor power and the new organizing it inspires is strongest. But big union resources and legal muscle may be needed to take on corporate leviathans, and the leaders of large unions often won’t cede decision-making power to members, instead favoring a staff-led strategy.

Brisack confronts this dilemma as the campaign is increasingly directed by the national leadership and staff of Workers United and its parent union, SEIU. Brisack, who writes that they were eventually ‘constructively fired’ from Workers United, harshly criticizes for SEIU for micro-managing things members had controlled, like the union’s social media, and what Brisack sees at a botching of a potential national boycott strategy.

STOP AND START

The union’s plan to muscle Starbucks into signing a contract has not yet been successful, but in February 2024 Starbucks agreed to negotiate with all its union stores, rather than pursue the store-by-store negotiations it had been dragging out for years. The “framework” agreement also contained a company promise to stop union-busting, and finally extended electronic tipping and raises to union stores.

Workers have been faithfully negotiating since (and 200 more stores have voted union), but the talks seem to be stalled on economics. In December 2024, the union revived the tactic of quick strikes to try to goose negotiations.

Brisack is skeptical of the short strike tactic, suggesting that with 13,000 corporate-owned Starbucks stores in the U.S., 600 don’t have enough leverage to move the company by striking. But while these and other tactical debates are live, the argument for salting has won, as other unions—I won’t name names—increasingly take up the tactic.

The book is an important contribution to the history of salting, and a valuable inside account of what is required to organize one of the nation’s top 20 largest private employers. It’s also a hymn of praise for Brisack’s café co-workers with all their creativity, courage, and dreams of a world with more heart.

To help with the Starbucks Workers United contract campaign in the lead up to Labor Day, sign up here.