A Candid Conversation About Queers in the Labor Movement with Longtime Union Activists Miriam Frank and Desma Holcomb

Union nurses represented at New York City's LGBTQ pride parade in 2018. Photo: NYSNA

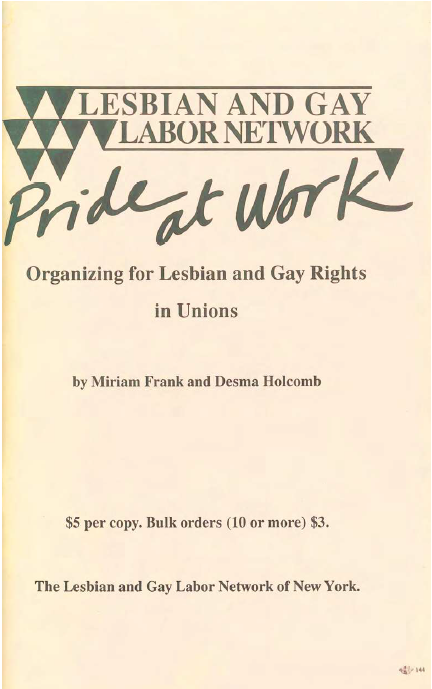

Pride at Work: Organizing for Lesbian and Gay Rights in Unions (1990)

Thirty years ago union activists Desma Holcolmb and Miriam Frank self-published Pride at Work: Organizing for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Unions, a 100-page handbook with practical advice on organizing for domestic partner benefits and grappling with the AIDS crisis at work.

Today for the first time, Autostraddle and Labor Notes are making the full booklet available for free download.

Union organizer Lena Ruth Solow interviewed the authors, now a long-married couple, about the making and legacy of what they merrily call a “naughty little pamphlet” or “the little pink book.”

It’s a charming and wide-ranging conversation that touches on their meet-cute on the New York subway and first date at a union picnic; post-marriage equality fights; the corporatization of Pride; how organizing sex workers is like organizing McDonald’s; mutual aid and casseroles; and the role of coming out. You can read the full interview here; an excerpt is below.

This pamphlet would later become the seed of Frank’s exhaustively researched 2014 book Out in the Union: A Labor History of Queer America. And the group behind it would help found the AFL-CIO constituency group Pride at Work, which now has active chapters in 20 cities. But at the beginning, what they had was a homespun distribution and organizing network. –Editors

Miriam: We would shlep it down to the post office! It was very mom and mom.

Desma: We distributed it out of our home, but we put notices about the existence of this resource in Labor Notes and circulated it to the other cities by word of mouth. So, the phone starts ringing and people from all over the country would call and they would not only say, “Can I have your book?” but “Can you give me some advice? We’re trying to bargain partner benefits or we’re trying to bargain a non-discrimination clause or—"

Miriam: “They’re trying to kill me at the auto plant!”

There was a vibe that people were starting to talk about this at all kinds of level of law and civic practice. There were queer caucuses—we didn’t use that word at all then—“lesbian and gay” caucuses in church groups and in all kinds of public organizations, not just the labor movement.

The thing is that there were some local unions that had non-discrimination clauses very, very early. The Ann Arbor bus drivers, famously, and Local 3882 had it, and that’s how it was. District 65 was always odd, there were sexist people in it but there were lots and lots of gay people! […]

Lena: What other kinds of advice did you give?

Desma: Well, I think one of the principles that we developed as union queer people is that it’s not just about identity politics, it’s about bringing people together with common interests. So, in the public sector union in NYC they decided to call it the Lesbian and Gay Issues Committee, not the Lesbian and Gay Committee. They wanted to be open to the parents of queer people in the union, and the children of queer people in the union, and anybody who thought this was a righteous idea in the union.

Miriam: They had great parties!

Desma: Miriam! I’m making a serious point here.

Miriam: Those parties are a serious point! OK, go ahead.

Desma: So, they got support from the retiree committee for partner benefits, because if you’re a widow and you have your spouse’s Social Security and you marry someone else you LOSE your former spouse’s Social Security. So, there’s a serious economic hit to getting married for straight people who are old. The disability rights committee was also involved because they have a similar situation where they get certain benefits, but if you marry someone and you have more income you lose that. And that affects your economic autonomy within the relationship and your independence.

I remember someone from Minnesota calling and saying, “I want to bargain partner benefits. What do we do?” And we always recommended bargaining for gay and straight partner benefits. You will more than double your coalition of individuals who care about this benefit. There are lots of legitimate reasons that straight people, especially if they’ve been divorced, might not want to get married again, even if they’ve been together for 10 or 20 years and they really need these health benefits.

It’s a winning approach and people would do that. That’s like a union head—it’s not an identity politics head—to think that way, so I think that was really important. Like in New York State, we’d had a liberal governor and then a conservative governor, and the conservative governor tried to repeal partner benefits. And all these blue-collar people are like, “My members have this and none of them are gay and get your hands off my benefits!” It sets you up for a broader coalition to defend it.

And, lo and behold, marriage equality comes along, and every place where partner benefits was only for gay people because they couldn’t get married, it’s disappearing! […]

Lena: What else do you want people to know about the labor movement?

Miriam: The labor movement has a lot of experience in expanding the idea of what it means to be human. And you know, it starts with the consequences of the Triangle Fire, it starts with the industrial mass production in the ’20s and ’30s when there weren’t unions in factories, and the labor movement is about the question of our humanity. So, yes it’s wages and hours and time clocks and a lot of other crap but I mean that all has to do with wanting to be treated like a human being. Always. […]

[O]ne of the things about a union meeting is—the boss isn’t there, you’re there because you want to and you’re there with your co-workers and you start talking to each other and sharing food and whatnot. It’s an amazing thing to be in an organization where you’re fighting to be more of a human being. And if what underlies that is a little bit more money so you can make it to work on a bus, or get your art supplies, that’s part of it too. So there’s mechanisms in the labor movement but it really is— [cat meows loudly] exactly.

Desma: Get her off the table, Miriam!

Miriam: It’s a very, very long-lived world, the world of organized labor, the world of people being in a movement. Sometimes, there’s no movement in a labor movement. There’s a lot of conservatism, there’s a lot of weirdness, there’s a lot of organized crime! And you can’t really think—if you start thinking about the labor world as like a totality—you have to find your place in it. And your place in it is usually at the workplace, at your workplace, where you’re working next to somebody else and are they gonna say yes or no to what you think about forming a union! As Woody Guthrie said, “You’ve gotta talk to the workers in the shop next to you.”