Our Faculty Union Exposed the University's Debt—And Who's Paying for It

A unity campaign at Salem State University, We. Belong. Here., called on the Board of Trustees to affirm the mission of serving a diverse population and to oppose privatization. Photo: MSCA/Salem

How should our university be funded? Should students be liable for its debts? Who are the winners and losers when public higher education is privatized?

These are questions that caused our faculty union, the Salem State chapter of the Massachusetts State College Association (MSCA), to reestablish its Political Action Committee—to educate about the funding crisis in public higher education and to call our members and students to action.

Salem State University, one of nine regional state universities in Massachusetts, is 15 miles north of Boston. Its student body is the most diverse of the nine, with 40 percent people of color. Our 7,000 students, most of them commuters with jobs, range from economically disadvantaged to middle class; many are the first in their families to attend college.

Our first major political action was a campus-wide teach-in in 2019 that documented how the long-term decrease in funding from state government has led to higher student costs and more student loan debt. The teach-in was conducted in 125 classes and engaged 69 faculty, 60 staff members, and well over 1,000 students.

While the teach-in raised awareness about student debt, it did not alter management's direction. The Board of Trustees continued to raise student fees as the primary source of campus revenue, while ignoring their own data that the number one reason why our students drop out is unaffordability.

WE BELONG HERE

We followed up this past winter with a unity campaign, We. Belong. Here., to assert that all members of our diverse campus community belong at Salem State. The campaign was in response to students and faculty of color, LGBTQ students, and undocumented students who were “just tired of not feeling safe here on this campus, not feeling wanted” and to the departure of several of the already very small number of faculty of color.

The campaign highlighted the need for adequate funding from state government as a precondition for equitable and quality education and for strengthening a sense of belonging for historically marginalized students. It called on the Board of Trustees to affirm Salem State’s mission of serving a diverse population, to oppose privatization, and to press state and federal officials for more financial support.

THEN CAME COVID

COVID then clearly exposed the problems of the university, including both inadequate state funding and a history of poor leadership decisions that prioritized ROI (return on investment) over a sound educational vision.

The administration's approach relied on “Business Intelligence” software and included efforts to cut “unprofitable” programs mostly in the liberal arts, such as glassblowing, Hip Hop dance, and several world language minors. At the same time it increased administrative expenses, such as adding associate vice presidents and associate deans and using outside contractors for enrollment, financial aid, requests for bids, and admissions.

As we continued to organize we learned, through the work of the Debt Collective and Bargaining for the Common Good, how campus capital debt undermines and de-democratizes public higher education. This was exacerbated, in Salem State’s case, by two factors.

First, in the past decade the university had carried out a construction boom focused on attracting residential students, including out-of-state and international students who pay higher tuition. The construction came with significant debt (about $200 million) and focused primarily on new dorm, dining, and fitness facilities.

Second, the Board of Trustees and the administration have been monomaniacally focused on a new plan, Project BOLD, which would downsize the footprint of the college from three main campuses to two (with the look and feel of a more traditional American college) and cut faculty in line with a projected reduction in the number of students.

The proposal, which is not entirely without merit, has three glaring problems: 1. The financing would deplete campus reserves and incur more capital debt. 2. It is not the university's greatest capital need, which is undeniably modernizing the largest instructional space on campus, a dilapidated 50-year-old arts and science facility. 3. The proposal was not created via an inclusive and transparent process.

CUTS AND FURLOUGHS PROPOSED

As COVID intensified in May and June, the Board started to prepare the 2020-21 budget for best-, middle-, and worst-case scenarios, contemplating cuts of 4 percent, 14 percent, and 27 percent of the total budget. The Board questioned (and delayed) a vote on tenure and promotions for faculty as being too expensive, infuriating faculty and many students. The cost of the tenure and promotion under scrutiny was less than one tenth of one percent of the total budget, whereas the cost of debt service for our new campus buildings was some $15 million annually—nearly 10 percent of the budget.

In line with its longer-term goals, the Board justified its proposed budget cuts by predictions of reduced student enrollment (from both demographic shifts and COVID), reduced state appropriations during COVID, ongoing debt service obligations for the buildings' construction, and an inability/unwillingness to use the university’s $15 million reserve fund because it was committed to Project BOLD.

Thus the Board and the administration, now operating in the middle case scenario, proposed massive cuts: laying off some 25 percent of adjunct teachers, reducing the number of classes offered, increasing class size (particularly in online classes), cutting “unprofitable” programs, and proposing five-week unpaid furloughs for all faculty and staff.

More than 200 faculty and staff watched these nightmare Board budget sessions in silence on Zoom, as the webinar format precluded our input, faces, or voices. But the budget sessions raised questions about why the campus has so much building debt and who is responsible for paying it.

INVESTIGATING DEBT

Therefore our union Political Action Committee investigated Salem State's capital debt with three goals in mind: how the debt impacts students, faculty, and the quality of education; how the debt fits within the neoliberal model of privatizing and de-democratizing public higher education; and how we could use the analysis to educate, organize, and mobilize students, faculty, and staff around the state.

We recruited a team of five faculty (none in finance) and two students who collectively did about 40 hours of research, analysis, and report writing.

We divided up the public documents on which we relied, namely, the Board of Trustees’ annual audit statements and meeting minutes, federal Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System data, State Building Department (DCAMM) reports, campus building authority (MSCBA) reports, and the state’s public employees salary database. We shared notes in a shared drive to develop this three-page document and to plan for outreach and organizing.

WHAT WE FOUND

What we found was sobering and both surprising and unsurprising. We found things that we had always suspected were true but we could now document—using the state's and university’s own words and numbers.

We found that in recent decades, construction of university buildings had changed from state-funded to largely campus-funded through interest-bearing loans managed by the Massachusetts State College Building Authority. A larger perspective on this can be found in Buying Time, by Wolfgang Streeck, which outlines the transformation of many Western societies from tax states to debt states (i.e., governments running predominantly on taxes to running predominantly on debt).

This debt was passed on to students in the form of increased fees. According to Massachusetts State College Building Authority documents, the lending “Authority annually sets and assesses rents and fees sufficient to provide for the payment of all costs of its facilities.” Moreover, the legislation “provide(s) for an intercept of legislative appropriations to the state colleges” (pages 5 and 15) if the debt service cannot be otherwise paid.

In other words, payment of the debt service, using public tax dollars, is legally prioritized over the educational purpose of the university. We had suspected this, but seeing it in print was astounding.

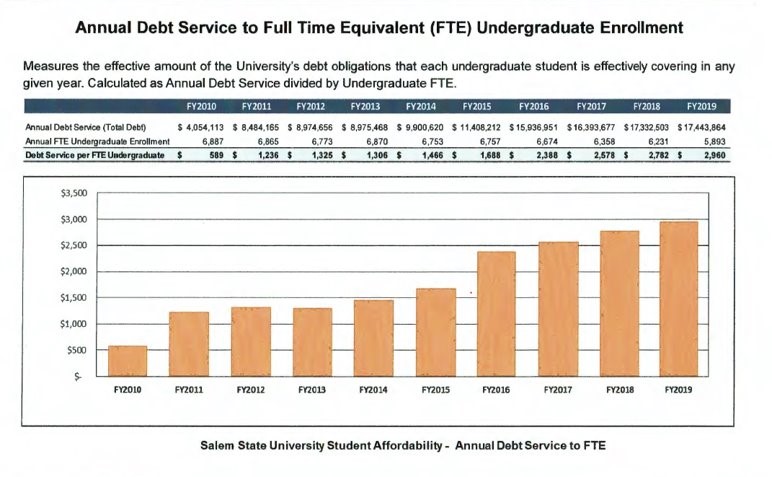

The actual figures were at least as astonishing. The annual cost of Salem State's debt service per full-time student increased from $589 in 2010 to $2,960 in 2019. Thus, the loans for public university construction ended up as debts owed by individual students on a large scale (see graph at right).

BAD MANAGEMENT DECISIONS

We also discovered that Salem State’s management decisions exacerbated this problem, above and beyond its unrelenting focus on Project BOLD to the virtual exclusion of other priorities.

The data suggested that declining enrollment was less likely a result of demographic changes, that is, the national and statewide trends for a declining number of high school grads, as the administration suggested. More likely enrollment fell because of Salem State’s higher tuition and fees in relation to other public universities in the state, which show stable enrollments.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

The data also showed a shift in expenditures away from instruction in favor of “institutional support” (administrative salaries and expenses).

This research created a framework for employees and students to understand that they were being called on to bail out the Board’s poor decisions—to take on debt for more dorms, higher-end facilities, and Project BOLD. And they were being asked to make up for the state’s neglect of public higher education by paying higher tuition and fees.

OUR PUSHBACK

These revelations have compelled our campus to push back. Actions included:

- More than 200 people attending the mid-June Board of Trustees meeting (where traditionally 4-6 have)

- A committed set of silent observers from our campus attending every bargaining session between our statewide union (MSCA) and the Council of State College Presidents (management)

- Some 70 percent of tenured faculty signing a petition to the President and the Board protesting austerity measures (to protect others, only tenured faculty were asked to sign and no signatures were published until 70 percent had signed)

- A recent public demonstration that garnered thousands of views online.

In addition, student organizations initiated two letters. One in April demanded a Pass/No-Pass grading policy for the semester, reimbursement of unused meal and dorm fees, and for the university to champion federal and state proposals for relief for students and universities. A second in July called for student, faculty, and staff input in decisions affecting SSU’s future, special consideration for survivors of sexual violence, and for non-union dining hall staff to be rehired in the next school year.

THE MONEY IS THERE

Despite COVID, the most recent campus financial statements are now depicting adequate short-term resources to avoid management's proposed cuts. This came about as a result of a less pessimistic state budget outlook; a refinancing of campus debt, allowing several big payments to be postponed—in part as a result of our pressure; and better than anticipated enrollment figures.

Nonetheless, the Board and administration continue to push for cuts and furloughs. Although faculty furloughs were rejected statewide by the MSCA, two other unions on campus, which had less job protection, accepted four-week furloughs.

And, while other MSCA campuses have agreed to use reserve funds to avoid furloughs and get through the crisis, SSU continues to refuse to use its reserves. Rather, Salem State trustees argue the reserves are necessary to preserve funds for Project BOLD, to maintain the University’s credit rating, and to prepare for a long-term crisis. They have threatened to initiate “retrenchment,” which could include permanent elimination of some 30 faculty positions.

In the longer term, this work has opened many minds on campus to a new perspective for progressive taxation, such as overturning tax breaks for large corporations and billionaires and taxing the $731 billion in wealth accumulated by 467 billionaires nationwide since COVID began ($17 billion for Massachusetts’ 19 billionaires).

The key to this project, however, is not just accumulating this information or even disseminating it beyond our campus, as we did in a Webinar run by the Debt Collective, but using the collection, framing, and distribution of the data to build power on our campuses to demand change.

A few campuses that do this can stimulate people on other campuses to do the same. That can organize students, faculty, and staff to better understand the role of capital debt in privatizing and undermining public higher education—and then to push for legislation for debt-free college statewide and even nationwide.

Rich Levy is recently retired from the department of political science and on the union’s executive board. Joanna Gonsalves is in the department of psychology and vice president of the union. They wrote on behalf of the Salem State University Capital Assets Research and Action Team.