Review: Pulling Clues From the Wreckage of PATCO

McCartin’s abundant supply of rank-and-file anecdotes lends the book credibility and emotional punch, but he does not dwell on them. His ambition is something more sweeping. The history of PATCO is, after all, more than an interesting case; it is the story of U.S. labor’s biggest strategic loss in half a century.

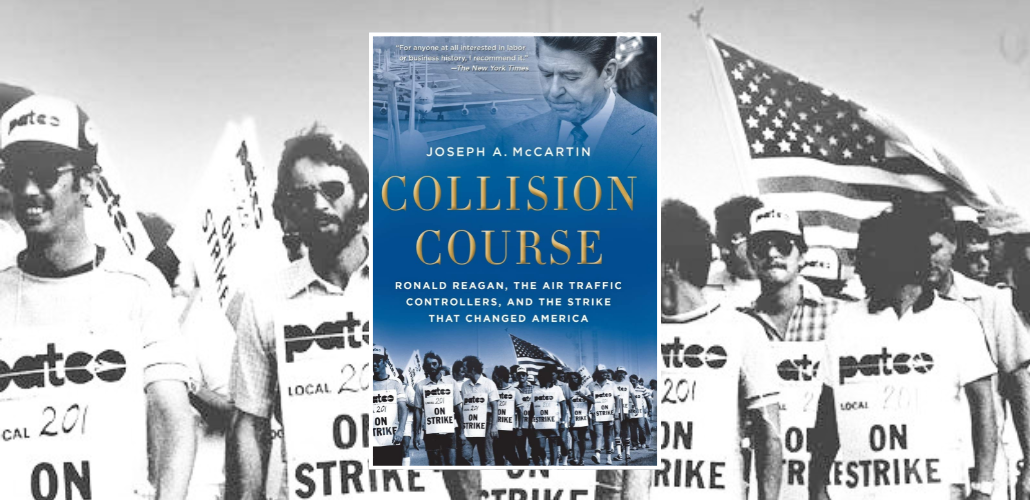

The meteoric rise and fall of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers’ Organization (PATCO) would be a fascinating case study for anyone interested in organizing strategy, even if the union’s spectacular destruction had not become a significant and devastating event for the U.S. labor movement. In less than 15 years, PATCO grew from nothing into a force to be reckoned with, pulled off high-profile national job actions that snarled the nation’s airports and forced the federal government to bargain over controllers’ wages, and then, in a catastrophic showdown with President Ronald Reagan, lost everything. In his new book, Collision Course: Ronald Reagan, the Air Traffic Controllers, and the Strike That Changed America, Joseph A. McCartin traces the union’s entire history, from its formation through the aftermath of the strike, exploring the context and impact of each major tactical choice along the way. If, to follow the book’s dominant metaphor, PATCO and the Reagan administration ended up on a “collision course,” McCartin with his painstaking research has assembled a “black box,” the flight data recorder that analysts use after a crash to piece together what went wrong. As a union organizer myself, I turned the book’s 370 pages as eagerly as a war buff devours an exegesis of battle.

McCartin, an associate professor of history and director of the Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor at Georgetown University, as well as author of the prize-winning Labor’s Great War : the Struggle for Industrial Democracy and the Origins of Modern American Labor Relations, 1912-1921, appears to have left no stone unturned in his research for Collision Course. He conducted over 100 interviews with PATCO leaders, strikers, non-strikers, family members, administration officials, pilots and others, and picked through countless archives. The result is a surefooted account, laced with tantalizing references to the individual lives who made up the larger narrative: the Alaskan activist who organized all the facilities in his state inside of two months, the Floridian leader in the “Choirboy” network of strikers who called herself a “Choirperson,” the New York controllers who recruited a pipe band and color guard to march them defiantly back into work after a failed job action and many more.

McCartin’s abundant supply of these rank-and-file anecdotes lends the book credibility and emotional punch, but he does not dwell on them. His ambition is something more sweeping. The history of PATCO is, after all, more than an interesting case; it is the story of U.S. labor’s biggest strategic loss in half a century. As the author puts it:

No strike in American history unfolded more visibly before the eyes of the American people or impressed itself more quickly and more deeply into the public consciousness of its time than the PATCO strike. No strike proved more costly to break. And no strike since the advent of the New Deal damaged the U.S. labor movement more.

The ordeal and its aftermath left labor severely weakened, and presumably anxious to avoid a repeat. In the absence of a thorough analysis of PATCO’s loss, it might have seemed safest to eschew big strikes altogether. In this book, McCartin has at last begun to piece together the much-needed strategic post-mortem, to figure out when and how PATCO might have had the opportunity to change course and avoid the disaster. (This is a quite different project than simply dismissing the entire strike as hubris, as New York Times reviewer Bryan Burroughs does; he seems to have read the book through a thick ideological lens). Sometimes there is more to learn from a loss than from a victory, and McCartin has made a significant contribution to the labor movement’s collective knowledge with this clear-eyed organizational biography.

PATCO’s seeds were planted in fertile soil. McCartin contextualizes the union’s origins in a ’60s New York that was alive, not only with the growing movements for racial justice and against the Vietnam War, but also with public sector labor militancy. Controllers in that city saw teachers, social workers and transit employees go out on strike in violation of the law and win significant gains, proving, as PATCO president Robert Poli would later repeat, that “the only illegal strike is an unsuccessful strike.” Meanwhile, controllers were worrying about conditions in their own industry, especially safety. To accommodate the growing volume of air traffic, they were forced to cut corners, routinely spacing airplanes closer together than the written guidelines required. To the air traffic controllers — proudly professional and highly trained, but overwhelmingly from working-class roots, and many from union families — the idea of organizing to address their concerns came easily. A tragic collision that brought two wrecked planes down on Park Slope, Brooklyn became the catalyst for action. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) blamed the crash on pilot error, but controllers knew it revealed systemic problems in the overburdened air traffic system. By late 1967 the New York controllers had built a local association and were reaching out to their colleagues nationwide.

To a unionist of my generation — I was born the year after PATCO’s collapse — it was an exhilarating surprise to read the union’s early history and discover how quickly the controllers escalated to militant direct action. Labor is far more gun-shy now. In my experience, most workplace actions today are symbolic displays like stickers, petitions or rallies, expressing workers’ feelings rather than flexing their hard power to interrupt the work process. I often reassure fearful new union members that the strike is rare, a tool of last resort. Not so for PATCO. Even before they had firmly decided to call their organization a union, PATCO members started exercising what they recognized as their greatest strength: the power to delay airplanes. The chronicle of the union’s victories and defeats as it learned to flex its muscle strategically forms the heart of McCartin’s book.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

PATCO’s first action, a work-to-rule slowdown in 1968, was a great success, in part because it did not require majority participation to be successful; “a minority of strategically positioned controllers” was enough to wreak havoc with flight schedules, draw media and public attention, bring the FAA to the table, and win dues for the union. The union’s next two actions, sickouts in 1969 and 1970, did not go as well; the latter ended with the controllers forced back to work, empty-handed, facing legal sanctions as well as growing hostility from pilots and the press. The FAA compounded this defeat with punitive action, targeting hundreds of activists with dismissal proceedings and thousands with fines. But the union’s fortunes turned again in 1971, when its ally the Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association (MEBA) and other port unions threatened to hold up a major wheat shipment from the U.S. to the Soviet Union. As part of a deal to move the wheat, President Richard Nixon agreed to rehire all the fired controllers.

Any union organizer can tell you the two biggest obstacles to workers’ taking action: fear and futility. The return of the fired activists struck a blow to both, teaching their fellow controllers a crucial lesson: “If these men could fight the government and win, why couldn’t any of their coworkers do the same?” (141). Without this tremendous boost to the members’ sense of collective power, it is hard to imagine that PATCO would have continued on its upward trajectory to a national strike within 10 years. Of course, in some ways the lesson was illusory, since the controllers had actually failed to defeat the government until stronger unions came to their aid.

These kinds of foreboding moments haunt the text. McCartin’s titular metaphor of a collision course, as opposed to a sudden freak accident, reflects his nuanced account of the many factors that led PATCO into disaster. He does not shrink from a close examination of union leaders’ decisions, but neither does he write off the failed strike as a simple case of pilot error. The union could not have anticipated some of the politics that led Reagan, himself a former union president, to change course, breaking his pre-election promises and treating the labor showdown as an opportunity for Cold War posturing, his “first foreign policy decision” (329). By the time the impending collision was obvious, it might have been impossible to avert it.

That said, PATCO also failed on labor’s own terms, falling short on strike participation and solidarity, in the book’s most wrenching passages. The controllers came so close; you glimpse what might have been. At one point in negotiations, Reagan’s team had actually conceded the most important issue by agreeing to bargain over wages. Then Poli received a phone call with the news that PATCO activists had not met their goal for strike participation. The government negotiators saw his weakness and the tables turned. Even so, McCartin notes, if only the pilots and airplane mechanics had walked out in solidarity with the controllers, the government could not have held out long against the strike. If only!

PATCO’s loss rippled through the United States. Ironically, to recruit and retain scab air traffic controllers, the government ended up giving them much of what the strikers had been demanding in the way of hours and pay. But Reagan’s war with the controllers set an example of aggressive union-busting that would be followed by “thousands of little Reagans” in both the public and private sectors in the decade that followed, with Phelps-Dodge and Hormel among the most famous. It would be unfair to pin all the blame for labor’s decline on PATCO, but certainly the catastrophic strike became a symbol of labor’s dramatic reversal of fortunes, from the growth and militancy of the 1960s and 1970s to the sad state of the movement today.

Yet this book is no elegy, and now is no time for the U.S. Left to cry quietly into its beer. McCartin’s last line declares PATCO’s past “prologue to a story still unfolding.” In fact, while I was reading the book in early 2012, plucky little Local 21 of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union achieved a climactic victory in its months-long battle with EGT, an arm of the massively powerful agribusiness conglomerate Bunge Limited. The triumph of the Longshore workers and their Occupy movement allies shows that, in this era of globalized corporate Goliaths and outsized finance capital, the building blocks of labor power are the same as ever: direct action and solidarity. As such, we have much to learn from a detailed assessment of PATCO’s steps and missteps. Historians will appreciate the thorough scholarship of Collision Course, but the book will be most useful to labor activists planning how to build power in their own industries.

This review first appeared at Left Eye On Books. Alexandra Bradbury, later a Labor Notes editor, was at the time an organizer with a health care union in Portland, Oregon, and a co-host of Labor Radio on Portland community station KBOO 90.7 FM.