The Hammer and the Dance: Why Reopening Now Will Kill

A line of cars comes through a coronavirus testing site in Detroit. The U.S. is millions of test kits behind what is needed to slow the virus's spread. Photo: Jim West / jimwestphoto.com, cropped from original.

This is a time of deep uncertainty. The coronavirus has been the leading cause of death in the United States since April 7, but scientist and doctors are only just beginning to understand it. It turns out that COVID-19 is much more than just a respiratory disease; it also attacks the brain, kidneys, heart, and blood vessels. Science, one of the world’s top academic journals, said that “the virus acts like no pathogen humanity has ever seen.”

If an enigmatic global pestilence weren’t enough, workers are being squeezed in an ever- tightening vice grip between mass unemployment and economic misery on the one hand and returning to work without adequate protections on the other.

Many states are now racing to reopen their economies, even though the daily number of new confirmed cases is holding steady nationally. In the absence of a comprehensive nationwide plan, if workers go back to their jobs now we will likely see further spikes in the number of cases, and more deaths.

To see why, it’s useful to start with an understanding of how things got so bad in the first place and why the move to reopen the economy now is so dangerous.

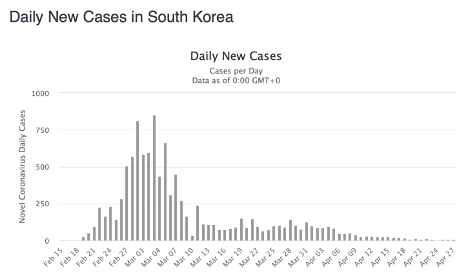

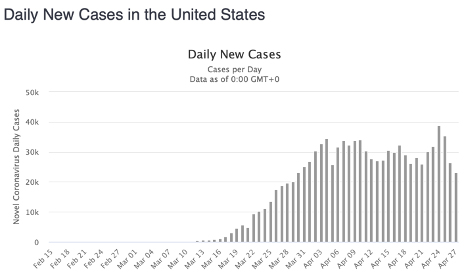

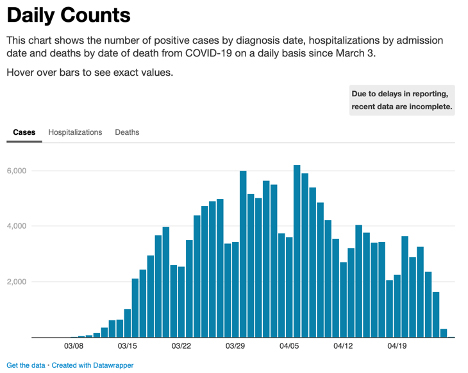

UNDERSTANDING GOVERNMENT RESPONSES, IN THREE GRAPHS

The U.S. and South Korea had their first confirmed cases of the coronavirus on the same day, January 20.

Within a week, South Korea’s government declared a national emergency and marshaled all of its resources for a coordinated effort to mass-produce test kits and then trace the contacts of infected persons going back two weeks, so the contacts could be quarantined.

By the end of March, South Korea had conducted over 300,000 tests, for a per capita rate more than 40 times that of the United States. As a result of testing, testing, testing, and tracing, South Korea went from a high approaching 1,000 new confirmed cases a day in late February and early March to averaging about 10 a day, as you can see in the first graph. On Thursday the Korea Centres for Disease Control and Prevention announced that the country had zero new domestic cases, despite 29 million voters participating in national elections just two weeks ago.

In the U.S., despite President Trump’s non-stop boasts, we are still facing a mass shortage of testing and there is little contact tracing. States have been left to hunt for test kits and figure out a policy on their own. In the second graph you see the result: the U.S. has not significantly reduced the daily average of new confirmed cases. We’ve merely plateaued the number of new cases and deaths at almost their highest level. Yet the U.S. is moving towards reopening the economy—which means that, at best, we will continue to see the same high number of new cases every day and that, at worst, cases and deaths will climb.

The third graph is from the Health Department of New York City, the epicenter of the disease in the United States. City residents dying from the virus per capita have outpaced even Italy, the hardest hit country in Europe. Now the number of new confirmed cases is declining, but the city is far from an aggressive plan like South Korea's. It continues to struggle to obtain the test kits needed and the state has barely begun a contact tracing program. Like every other state, New York has been forced to cope without any federal effort to standardize a response.

Even if New York City does manage to significantly reduce the spread there, the virus is spreading more rapidly in other parts of the country. And absent a national plan to dramatically increase testing and tracing capacity overall, the number of new confirmed cases and deaths is not likely to fall if states rush to reopen their economies and employers demand that workers return to their jobs.

WHAT THE FUTURE HOLDS

Probably at least 85-90 percent of the U.S. population is still susceptible. That means the virus still has a huge field to play in.

A combination of deregulation, lack of coordination, bad tests, and bad sampling methods means that studies of the total rate of infection are seriously flawed, but the consensus is that the vast majority of the population has yet to be exposed. This means we are nowhere close to “herd immunity", the point at which a majority of the population has developed some level of immunity. The World Health Organization has ballparked the infected percentage of the global population at about 2 to 3 percent.

The White House has continually asserted that a vaccine is 12 to 18 months away, but many scientists believe that a vaccine will likely take years to develop, if one ever comes at all.

There is a tremendous, unparalleled global effort by scientists to discover and manufacture a vaccine at record speed, but the challenge before them is daunting.

There are no successful vaccines for any of the seven coronaviruses that infect humans and there are serious doubts among some scientists that it is even possible to vaccinate against coronaviruses. The fastest vaccine ever produced was for the mumps—and it took four years to produce. The failure to develop a successful vaccine against HIV despite decades of research is indicative of how challenging the process can be.

If a vaccine were created in 18 months (possibly cutting ethical corners in the process), it would be entirely unprecedented. James Hildreth, a leading international immunologist, told the Wall Street Journal, “I’m very cautious in telling people we will have a vaccine for Covid-19.... All the other major vaccines we have—for measles, Ebola—have taken a minimum of seven years, and some as long as 40 years.” Multiple health experts say a vaccine is unlikely anytime soon. Producing a vaccine by 2022 “is very optimistic and of relatively low probability,” Robert van Exan, a biologist with decades of experience in this area, told the New York Times.

If a vaccine is not going to be available any time soon, then that means our best hopes are to find drugs that slow the spread of the virus in the body—so people who do catch it don't die—and social distancing to slow the spread of the virus in the population.

There are currently no approved drugs that combat the virus itself, but there might be in the future.

Only 90 anti-viral drugs have been approved for use in the U.S. since 1963.

Scientists have been studying whether any currently existing anti-viral drugs could be used with COVID-19 patients. Initial studies of hydroxychloroquine have shown the drug to be a bust, but remdesivir has shown modest benefit to the most severe patients.

Many other drugs are now under study and in clinical trials, but given how few anti-virals have ever been shown to be safe and effective, it may be a while before we have a proven treatment that can effectively limit the coronavirus’s ability to rampage through the body.

The disease is not going to die down much in warmer months.

While initial studies are not conclusive, the National Academies of Sciences say that the virus might transmit somewhat less efficiently in environments with higher temperatures and humidity, but it is not likely this will reduce its spread significantly. The virus is already spreading rapidly in tropical countries, and Australia and Iran saw fast distribution in warm climates.

There is good reason to doubt that immunity is permanent and that antibody tests are good indicators of immunity.

Immunity to seasonal coronaviruses (which cause the common cold) starts declining a couple of weeks after infection. Immunity to both the old SARS from 2002 and MERS, cousins to the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), has been shown to be short-lived, about one or three years.

The growing consensus among scientists is that exposure to SARS-CoV-2 provides some immunity for some unknown amount of time, but the WHO has warned that there is no evidence that someone who tests positive for antibodies is immune. Some evidence also suggests that infected people with no symptoms or mild symptoms might not produce enough antibodies to develop immunity.

THE HAMMER AND THE DANCE

Our country essentially faces a choice between options: mitigation and suppression.

Mitigation means slowing but not stopping the epidemic. With mitigation, the majority of people return to work, schools and universities reopen, but we try to slow the spread of the virus through mass testing and contact tracing, home isolation of suspected cases, home quarantine of those living in the same household, and continued social distancing of the elderly and high-risk groups.

According to research by the Imperial College of London’s COVID-19 Response Team, resuming life as normal with these mitigation protocols in place will still lead to outbreaks in workplaces, nursing homes, and communities. ICUs will again be overwhelmed, thousands will die—and we'll need to lock down again.

Suppression means using lockdowns for as long as necessary to keep the number of new cases as close to zero as possible. Suppression means social distancing of the entire population by closing non-essential businesses, schools, and universities—what much of the country has been experiencing since early April.

Moving back and forth between mitigation and suppression is the approach now favored by many governments around the world and by many U.S. governors. (South Korea did not have to resort to a country-wide lockdown like the United States did because its testing and tracing program is so thorough.)

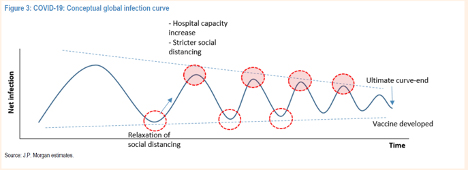

This seesaw approach has been called "the hammer and the dance," where “the hammer” is bringing everything to a halt through lockdowns and “the dance” is accepting a relatively large number of deaths while keeping the economy humming along. The idea is to continue alternating the hammer and the dance until a vaccine is eventually developed.

If we reopen now, without nearly enough testing and virtually no contact tracing, we will have to lock down again once the next wave of the pandemic hits.

WHY THE RUSH TO REOPEN?

What is fueling government officials' rush to reopen? One reason is that Trump believes skyrocketing unemployment and a plummeting stock market are bad for his re-election chances. Another is that employers are eager for some level of consumption to be reignited so that they can resume making profits. In the end, it mostly boils down to big business being prioritized over public health.

How long could the hammer and the dance last? Harvard scientists have projected that, absent a vaccine or effective treatments, it will take two to four years of alternating between suppression and mitigation before we achieve herd immunity. We might be facing many months, possibly years, of seeing cities and states open up their economies, followed by eruptions in confirmed cases, followed by another lockdown.

This is how JP Morgan illustrated this idea. The protocol is to wait till infections are very low before relaxing social distancing.

But the U.S. has not brought new infections close to zero as JP Morgan “recommends.” We’ve merely plateaued the number of new cases and deaths, as seen above in the second graph. Effectively, instead of reopening the economy at the bottom of the curve, with cases low, we are reopening while holding steady at near the highest point of daily new cases.

So we are essentially using the highest rate of confirmed cases and deaths as the new baseline—the new normal—for moving forward with the “dance” of reopening the economy.

Since the decision to open up and close down is being left to the states, most of which are still struggling to obtain test kits and even begin contact tracing, there is no common understanding among government officials or the public about when a state should lift or resume lockdown measures. It will likely depend on how much pressure is put on officials when the time comes.

In an April 15-20 poll, 80 percent of those surveyed supported continued lockdowns. In an April 7-12 poll, two-thirds said they were more worried about their state lifting restrictions on public activities too quickly, vs. one-third worried about “not quickly enough.”

But who has a louder voice in politicians' ears, the people or the corporations? If we needed another proof that corporate interests dominate governments, this is it.

Low-wage workers will continue to bear the brunt. In slaughterhouses where the vast majority of workers are Black or Latino immigrants, workers have never experienced a lockdown nor any measures to slow the spread. As would be expected, their workplaces are hotbeds for the virus.

Transit workers, grocery workers, postal workers, and health care workers have had to fight tooth and nail for protective equipment. The more people use transit and go to retail stores, the more the virus will spread. The more the virus spreads, the more our hospitals will be overrun.

An Alternative Model

by Mike Davis

A phased reopening has to be based on the availability of PPE and testing. This is what is being proposed by Dr. Michael Osterholm, an infectious disease epidemiologist and director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

Only with enough resources on hand and testing in place can we pursue what Osterholm calls the “thermostat” approach: when infections increase, new stay-at-home orders are given.

He predicts that if the economy were entirely reopened right now, without enough testing or contact tracing, 16 million people would be hospitalized and 5 percent would die. That’s 800,000 deaths.

But the Osterholm plan needs four improvements:

- As states begin mitigation strategies and reopening their economies, unions must be at the table, as well as actively representing workers at the workplace.

- We need workplace safety committees with worker majorities active at every worksite.

- Until a vaccine or other intervention ensures safety, workers of all ages who have serious preexisting conditions should be guaranteed job security, preservation of seniority, and income support.

- In every workplace provision of PPE, including an N-95 mask, must be standard and non-negotiable. Surgical masks alone won’t cut it.

Mike Davis is the author of Ecology of Fear and The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of Avian Flu.

CORNERED EMPLOYERS LASH OUT

The picture is not bright for employers either. Mass unemployment means consumer spending is going to be down for a long time. Companies whose profits plummet will respond by more zealously demanding concessions, busting unions, pressuring workers to work harder so they can lay off “excess” capacity, and pressing governments to cut their taxes and strip away environmental and workplace regulations. The past two months have seen countless cases of companies refusing to alert their employees to COVID cases at work and forcing them to work without PPE.

Likewise, state governments facing massive deficits will seek to dissolve union contracts or demand concessions, try to get rid of their pension obligations (as suggested by Mitch McConnell), and gut public services.

Unions should prepare for what is coming: a drive for concessions fiercer than we’ve ever seen, in the midst of mass unemployment. And all workers, whether they have a union or not, should take collective action to protect themselves. Click here for many examples and strategies.

FOLLOW WHAT HAS WORKED

Here are four steps the U.S. government could take if it wanted to follow the successful models for fighting the virus being used in South Korea and Germany:

- Use the Defense Production Act to redirect our domestic manufacturing capacity towards the mass production of COVID-19 test kits and PPE.

- Start a national program for systematic contact tracing. To work, this program will require the hiring of hundreds of thousands of workers, which will have the added bonus of helping to lower unemployment.

- Based on the information obtained from mass testing and tracing, the CDC should produce predictive models that show whether the spread of the disease is expected to escalate, hold steady, or diminish in the coming weeks, rather than states' determining their course of action based on competing and divergent models.

- Remain on national lockdown until we have reduced new cases close to zero and we have a national plan in place that uses testing and tracing. That could then enable us to cautiously open the economy back up while mitigating the spread of the virus.

Comments

some corrections

Besides being inundated by often contradictory data (a normal condition in science), we acquire new data about the novel coronavirus at a rapid rate, and so some information reported mere days before becomes dated. So, I wanted to add a few tweaks to this excellent piece. First, you note that, "This seesaw approach has been called "the hammer and the dance," where “the hammer” is bringing everything to a halt through lockdowns and “the dance” is accepting a relatively large number of deaths while keeping the economy humming along. The idea is to continue alternating the hammer and the dance until a vaccine is eventually developed." The "Hammer and the Dance" -- both the version proposed by the Imperial College and the named version proposed by Thomas Pueyo -- are meant to drive the R0 below one, and keep it there. The relevant referent variable is NOT mortality but transmission, and the way this is phrased gives the impression that the models propose acceptable death rates, which they do not. They do not presuppose any particular level of mortality (they make the point that such would be a POLITICAL decision). Both simply make the observation that political leaderships will face pressures to maintain economic activities while containing the pandemic. Second, this -- " there is no evidence that someone who tests positive for antibodies is immune" -- is no longer true. A recent large cohort study at Mt. Sinai Hospital in NYC found that most patients (non-critical cases) seroconverted (produced antibodies) and that these antibodies confer immunity (neutralizing antibodies). The caveats are those stated: we don't yet know about asymptomatic cases, nor severe cases, nor the temporality of immunity, among other things. Nevertheless, this is good news. There is also some potentially promising news about the use of blood serum from convalescent cases or the generation of monoclonal antibodies based on that research. One problem, here, is that convalescent serum is likely to be in short supply (given that population prevalence is on the order of 1-2% in most places).