Chicago Charter Teachers Fight for Their Jobs, And a Union

Two days after filing for union representation in late May, teachers at a Chicago charter school got some bad news: an ominous letter from the administration arrived at home.

Sent by overnight mail, the message announced school officials were recommending that the school be closed next year.

Organizing was underway at Youth Connection Leadership Academy, an alternative high school located in the historically Black Bronzeville neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side. It’s one of 23 in a local chain of schools for at-risk students and high school dropouts run by charter operator Youth Connection Charter Schools (YCCS.) Teachers have unionized in four other schools in the network.

“The timing definitely seems suspect,” said art teacher Lydia Merrill.

YCLA teachers decided to organize last fall after the administration announced it would be extending the school day. Teachers were frustrated over their lack of input on a change that would affect childcare schedules, second jobs, and students’ night school and work schedules. Almost all 20 teachers came to an ad hoc meeting and quickly started talking union.

Teachers across Chicago are expressing frustration with the charter system. Low pay and lack of job security lead to poor teacher retention, which creates instability for teachers and students alike. Teachers fearing for their jobs are afraid to test new strategies and advocate for their students.

Other concerns are closer to the wallet. A teacher at the academy, Virginia Coklow, said, "In some cases, experienced teachers with many years of vital contributions to the school are being paid less than first-year teachers."

The charter teachers managed to keep the campaign secret until submitting a petition for representation in May. Then the hammer fell.

Though they were prepared for the possibility of employer retaliation, the closure announcement came as a shock to YCLA teachers. They’d gotten letters confirming their jobs for the next year just weeks before.

The administration justified the closure by citing claims of poor performance, which were also a surprise. The school’s charter had been renewed by the district only months before, giving it the green light to stay open for three more years.

A student’s grandmother told union organizers that the charter operator, calling YCLA its "flagship school,” had recommended she send her grandchild to the school just days before the closure announcement.

DENSITY STILL LOW

The entire school staff turned out for a May 31 board meeting, where parents and students spoke out against the proposed closing.

The pressure seems to have worked—for now. The board agreed to hold off on making a decision to close or restructure, keeping the school open for the time being. They’ve also agreed not to challenge the union’s certification.

If the teachers union at YCLA is eventually certified, the school will become the 13th unionized charter in the city, creating about 9 percent density in a city with an ever-growing charter population.

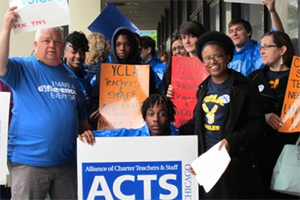

Charter school organizing is relatively new territory for teachers unions. The American Federation of Teachers began its charter organizing project just over 10 years ago. ACTS Chicago, a project of AFT, started organizing in the 2007-2008 school year. (Charter teachers are in a different local than public school teachers: A state law says their bargaining units must be "separate and distinct" from those of public school employees.)

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Charter teachers seeking to unionize uniformly want a voice in curricular decisions; input on working conditions like schedules, class sizes, and length of the school day; job security; and higher pay in an equal and clear-cut system.

Their goals stand in contrast to the benefits that charters’ boosters tout: the “flexibility” to make decisions like expanding the school day without having to negotiate with organized teachers; the ability to fire “bad” teachers at will; and low costs due to high turnover, the use of young teachers, and no rules to follow regarding pay.

“Teachers have left because they don’t like working in the environment we have,” Merrill said. “A good quality school should not have such high teacher turnover every year.”

Illinois standardized test data released in November showed highly uneven performance in Chicago charter schools. Two large multi-site charter operators underperformed public schools at every single campus, while only one of the city’s nine large operators showed consistently better results than traditional public schools.

Many teachers question the claim that charters are cheaper and more efficient than public schools, particularly with the money they spend on advertising to attract students and influence public opinion. "They had two full-time lobbyists last year," Coklow said, "that they paid $120,000 to lobby the city and state. That's $6,000 per union member at YCLA."

“Every time we organize a charter school we take away some of the potential of charters to totally privatize education and weaken teachers unions,” said Brian Harris, president of Chicago’s charter school union, the Chicago Association of Charter Teachers and Staff. “If charters aren’t being used as a tool against teachers unions, then why is it that every time we try to organize a school, we get into a big protracted battle?”

BOSS RESISTANCE

Harris is himself a veteran of a just such a battle over charter unionizing. As a second-year teacher at Northtown Academy, he began organizing a union with his co-workers after administrators announced that teachers would pick up a sixth class in lieu of the study hall period they had used for prep time. Teachers at the two other Civitas schools in Chicago joined the organizing drive.

Civitas teachers filed for AFT representation in 2009 through a card-check process with the Illinois Educational Labor Relations Board. Management then challenged the union’s certification at the National Labor Relations Board, claiming that Civitas was a private employer—despite running on public funds—and thus not within the jurisdiction of the state of Illinois.

The legislature passed a law in June 2009 giving the IELRB jurisdiction over charter employees, but not before the NLRB ruled in Civitas’s favor. Employees at the three Civitas schools had to unionize again, this time through a secret ballot election.

“They were acting like whether it was a matter of state or federal law was the most important thing in the world. It’s obviously just a matter of delaying, even though the employer is never going to say it,” Harris said.

Even after state law placed charter teachers squarely within the state’s jurisdiction, charter operators are still trying to stall unionization, with moves like Chicago Math and Science Academy’s 2010 appeal to the NLRB after retaining a union-busting law firm. Administrators at Latino Youth Alternative High School, which belongs to the same chain as YCLA, are refusing to bargain until the NLRB decides that case.

ACTS expects a favorable decision in the next few months.

HAPPY HOURS

Despite stiff employer opposition to unions, interest among charter teachers is growing. ACTS is currently speaking to teachers in more than a dozen schools and expects to launch several new union drives. To build relationships, ACTS hosts regular happy hours and gives professional development courses.

As the YCLA teachers wait for the dust of their own unionization battle to clear, some are drawing inspiration from the Chicago Teachers Union, whose members recently voted overwhelmingly to authorize a strike.

Lydia Merrill attended a giant CTU rally May 23. She was deeply inspired by the sight of thousands of teachers in red shirts, chanting “fight!” “I sent pictures to the staff,” she said, “saying, ‘This is what we could become.’”