Which Way for Labor on California's "Clean Money" Elections Initiative?

After leading the charge to rebuke Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger's slate of anti-labor ballot initiatives in 2005, California unions may play the key role in passing an election reform bill, the "Clean Money and Fair Elections Act" (or Proposition 89), in upcoming state elections.

Proposition 89 calls on those running for elected office to "do the right thing" and choose public financing over private sources. Under Prop 89, candidates collecting a specified number of five-dollar contributions from registered voters would qualify for public dollars. Those taking this option must agree to forego conventional fundraising efforts in exchange for receiving a lump sum of money to run their campaigns.

THE UNION DIVIDE

In contrast to 2005, when labor united in opposition to Schwarzenegger, unions are divided over Prop 89, which would limit campaign contributions from not only corporations and wealthy individuals, but unions as well.

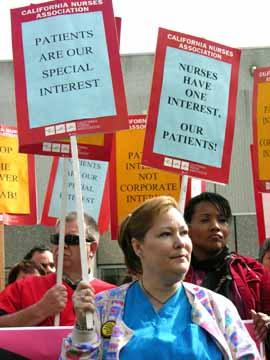

Supporting the initiative is the California Nurses Association (CNA). Opposing it is the California Teachers Association. Between these two sides sits the AFL-CIO's California Labor Federation (CLF), which has not taken any position at all.

CNA both sponsored Proposition 89 and spearheaded the petition drive to get it on the ballot. According to CNA Executive Director Rose Ann DeMoro, the measure "will change the balance of power in California, giving everyday people the ability to run for office and to stop the corrupting influence of money in politics."

HEALTH CARE REFORM

For the union, this is an important initial step towards its ultimate goal of single-payer public health care. The union claims that clean money will lead to legislatures that are not beholden to "special interests," and that politicians who are "not bought" will act in the public interest.

In such a scenario, just health care reform seems a real possibility.

Meanwhile, CTA has misgivings about a measure that it says neither enforces existing campaign finance limits nor addresses what wealthy candidates can spend on their own behalf-particularly since the measure would curtail the union's political participation.

In noting that the initiative's passage would limit future CTA campaign contributions to $10,000, spokesperson Sandra Jackson stated that while something needs to be done about campaign finance reform, Prop 89 "is not it."

The CLF's "no recommendation" on Prop 89 came from an executive council vote that was confirmed on the floor of the federation's convention. The debate in the CLF revolved around concerns that language in the initiative written to restrict corporations would also affect several major unions.

Specifically, says CLF spokesperson Chloe Osmer, Prop 89 could restrict unions with "income producing organizations" attached to them, such as the Firefighters and Operating Engineers, which run print shops. Thus, in Osmer's view, unease within the federation was largely technical rather than philosophical.

PUBLIC FINANCING

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

The Supreme Court held in the 1970s that spending money in an election campaign is a form of speech protected by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The one exception, according to the court, would be where such limits were a condition of candidates accepting public funding. The post-Watergate period saw a number of states establish public funding for certain races. These programs have generally done little to limit the political influence of wealthy individuals and moneyed interests.

Taking a different approach in 1996, Maine voters passed a ballot initiative providing for what supporters called "clean money" public financing. Advanced by unions and public interest lobbies, two groups often at odds with one another, the measure faced almost no organized opposition. Today, almost 80 percent of the Maine legislature is composed of candidates who chose to run "clean."

Arizonans adopted a similar measure in 1998 with the help of organized labor. About 50 percent of current Arizona legislators ran voluntary "clean" campaigns, as did ten of twelve statewide officeholders, including the governor.

USING CORPORATE MONEY

Like it predecessors, Prop 89 does not require candidates to use public financing. It differs from them, however, in its revenue scheme.

Maine's system depends upon voluntary taxpayer "check-off" contributions and a dedicated allotment of money from the state's general operating fund each year. Arizona's fund relies on voluntary taxpayer "earmarks" as well as a surcharge imposed on civil and criminal fines.

California's "clean elections" process would be paid for by a two percent increase in the income tax rate levied on corporations, banks, and other financial institutions. Unsurprisingly, initiative opponents such as the Chamber of Commerce and the Business Roundtable have zeroed in on what they call a "tax increase" that will harm the state's economy.

POLITICAL PRIORITIES?

So what to make of organized labor's differences on the "clean money" proposal?

Sandra Jackson downplays the differences, noting that "we've disagreed on some other things in the past." She also points out that California unions "just worked with the nurses and other unions on SB 840"--legislation that will provide affordable health insurance to all Californians and protect their right to choose their own physician.

Osmer notes that Prop 89's primary proponents and opponents in labor "are outside our state AFL, with CNA leading the campaign and CTA opposing it. While there will be an array of issues and candidate campaigns that we'll be working on, our primary focus will be on the governor's race."

Osmer concludes, "Given labor's determination to remain unified around defeating Schwarzenegger in November, at this point it doesn't look like our differences on Prop 89 will weaken our efforts."