Non-Union, Low-Wage Workers Are Finding a Voice as Immigrant Workers Centers Grow

August 2003

Editor’s note: To kick off our series of articles on workers centers, we asked Janice Fine to present an overview drawn from her past research on new approaches to low-wage worker organizing and her recently begun study of immigrant workers centers. Labor Notes encourages written response to this piece and others in the series.

Because many low-wage workers today are as likely to be struck by lightning as to be approached to join a union, many community-based efforts around work and wages have organized outside the context of labor unions. Of course some unions, such as the Service Employees with their Justice for Janitors and home health aid campaigns, are targeting low-wage workers. But these drives are still the exception.

The bulk of immigrants to the United States today, documented and undocumented, work in low-wage jobs. These workers toil overwhelmingly in the private sector, at jobs that are born non-union, in industries that present huge barriers to unionization.

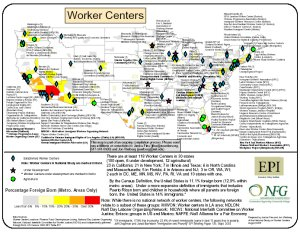

Workers centers-a new type of community-based labor organization with the dual role of raising wage standards and giving low-wage workers a voice in the broader society-are attempting to fill this void. Most have arisen in communities of newly arrived low-wage immigrant workers.

WORKPLACE RIGHTS

A minority of these organizations are unions, or have some affiliation with a local or international union, but most are not affiliated with unions at all. They are modest-sized community-based organizations of low-wage workers that focus on issues of work and wages in their communities.

Workers centers pursue their mission through a combination of strategies: service delivery: such as legal representation to recover lost wages, English as a Second Language classes, and job placement, advocacy: speaking on behalf of low-wage workers to local media and government, and organizing: building an association of workers who act together for economic and political change.

The centers arise in “generational waves” because the need for them occurs when new groups arrive and have to find ways to negotiate with the larger society. In the late

1970s and early 1980s, long-time activists in older immigrant communities like New York City’s Chinatown, along the Texas/Mexico border, and among Chinese immigrants in Oakland, organized the first contemporary workers centers.

Examples include: the Chinese Staff and Workers Association, La Mujer Obrera, and the Asian Immigrant Workers Advocates (AIWA).

New immigration in the late 1980s and early 1990s, from particular regions of Mexico, El Salvador, and other Central and South American countries as well as Southeast Asia, led to the emergence of a second wave of immigrant workers centers.

Examples include: Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles and Korean Immigrant Worker Advocates also in Los Angeles, the Workplace Project in Long Island, and the Tenants and Workers Support Committee of Northern Virginia.

A new wave of centers came on line in just the past three or four years. More are in the South, a number are connected to the National Interfaith Committee on Worker Justice, and more of the centers are working with labor unions than in previous waves.

Examples include: Restaurant Opportunities Center in New York, the Chicago Interfaith Worker Rights Center, the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, the Minneapolis Resource Center of the Americas, and Casa Mexico, also in New York.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

The centers arise in ‘generational waves’ because the need for them occurs when new groups of immigrants arrive.

These immigrant workers centers have created dynamic, in many cases worker-led, organizations of constituencies who had no place else to turn to pursue work-related issues.

STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES

They have built a culture of democracy and participation. They have developed strong leaders from within these constituencies and strong allies in the larger community. They have had a concrete impact on the way the media reports and the larger public perceives immigrants as well as low-wage worker issues-dramatically changing the climate and altering the terms of debate.

They have won back-pay awards for thousands of workers. They have drafted, campaigned for, and won some important new public policies and succeeded in blocking other policies that would have exacerbated workers’ problems.

Yet their numbers remain relatively small and they have not been able to regularize membership through systematic collection of dues, leaving them dependent upon outside sources of funding. In addition, very few of the organizations have succeeded so far at large scale economic intervention in labor markets through worker organizing efforts. So far, they seem best at bringing community organizing strategies to bear on labor issues through politics and worst at doing so through economic strategies.

Those who would stand in judgement of the weakness of workers centers’ impact on the labor market must acknowledge their considerable successes, made in the face of scarce resources and almost no regional or national infrastructure. While it is tempting to suggest that labor organizing be done by unions, the sad fact is that unions are doing little organizing among these workers and those few that are have limited resources in terms of meeting the enormous unmet organizing demand.

Janice Fine has been an organizer for more than 20 years. She directs the Economic Policy Institute’s National Immigrant Workers Centers Study.

Workers Centers

Labor Notes staff: Introduction to roundtable discussion

Janice Fine: Non-Union, Low-Wage Workers Are Finding a Voice as Immigrant Workers Centers Grow

Saru Jayaraman: In the Wake of September 11: New York Restaurant Workers Explore New Strategies

Cindy Cho: In Koreatown, Los Angeles Workers Center Fights for Immigrant Worker Rights

Renuka Uthappa: First National Meeting of Worker Centers Discusses Strategies, Vision