For Pride Month, Here’s Your Definitive Reading List on Queerness and Work

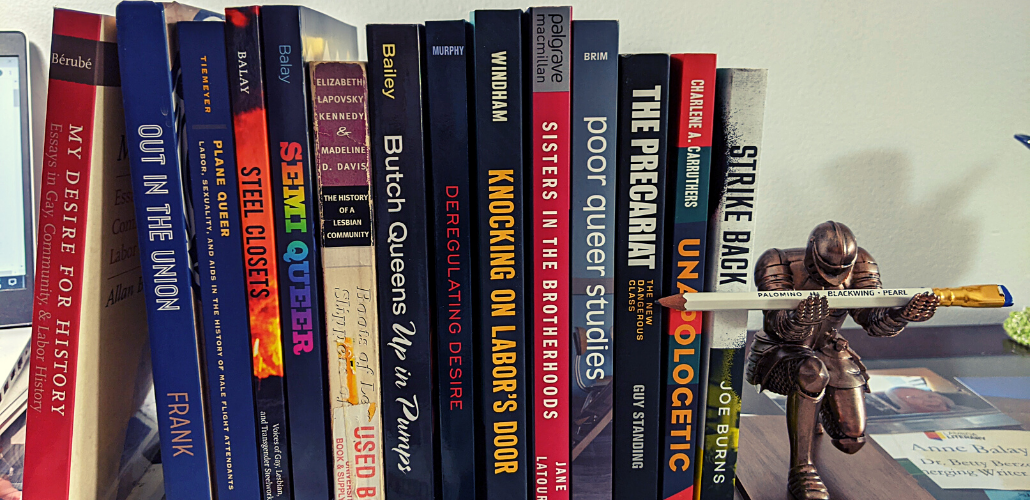

These books enable us to think about labor organizing “queerly”—in ways that undermine power hierarchies. By calling attention to and challenging management’s authority, queer organizing enables a collective resistance that’s for everybody. Photo: Anne Balay

I have worked as a car mechanic, an English professor, a truck driver, and a union organizer—and through it all I have been a lesbian.

The more blue-collar, dirty, and stigmatized the job was, the easier it was to be gay. At a small independent car shop and then again driving long-haul trucks, people ribbed me about my sexuality, laughed with me about my body and my gender expression, welcomed my lovers and my kids, and provided a context in which I could breathe and expand and thrive.

As a professor and organizing adjunct faculty for Service Employees (SEIU) Local 1, on the other hand, I feel loud and difficult. These workplaces mouth acceptance, but they also indicate that sexuality does not belong at work. I’ve even gotten fired for being a queer who writes about queers and work.

These experiences have led me to think and write about queer and trans people on the job. Early writing about LGBT folks focused on sexual and social culture, but this century has seen an increase of books that consider the workplace. Here I’ll summarize some nonfiction books that focus on working-class labor.

These books are crucial not only because they present the heroic and glamorous lives of queer workers, but also because they enable us to think about labor organizing “queerly”—in ways that undermine power norms and hierarchies.

Thinking queerly about unions means that instead of focusing on access to specific rights (like more compensation or marriage equality) we focus on shifting how power functions. By calling attention to and challenging management’s authority, queer organizing enables a collective resistance that’s for everybody and changes everything.

Books about ‘Working While Gay.’

Allan Bérubé, My Desire for History: Essays in Gay, Community, & Labor History (North Carolina, 2011). Bérubé founded this field through his career from the 1980s until his death in 2007. He combined archival and oral history research about gay people in union jobs with personal reflections on class, sexuality, and scholarship. He was a historian who pieced together the cultural and political shifts that led the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union to become a gay hub in the 1930s.

In this book, Bérubé tells the stories of these workers as they build power in their workplaces. He put together a slideshow and lecture about these men that he delivered in union halls and community centers. He wanted to change how we think about sex, class, and work, which he could only do by engaging a wide public audience. He tells solidarity stories that are campy and deep and remind me that change is possible, and that it is queer. I get goosebumps. Every. Single. Reading.

Miriam Frank, Out in the Union: A Labor History of Queer America (Temple, 2014). Frank is a union insider first and an academic historian second, following squarely in Bérubé’s footsteps. Her book describes the simultaneous rise of the LGBT rights movement and an upsurge in labor organizing and activism in the 1960s and ’70s, and how their shared goals and shared foes shaped the trajectory of each.

The joy of her book is in the stories: Frank personally interviewed more than 100 labor activists. We learn about drives to organize AIDS clinics and lesbian-owned car shops; we hear detailed, human drama about all kinds of jobs; and we get a carefully documented account of how unions and queers have helped each other find a way forward during difficult times.

Phil Tiemeyer, Plane Queer: Labor, Sexuality, and AIDS in the History of Male Flight Attendants (University of California, 2013). This book links changes in how flight attendants’ work is viewed and who does that work to corporate profits. It’s a detailed study of one particular job as it has changed over the past 100 years, making the point that the workplace is sometimes where LGBT community emerges.

In the late 1930s, as white women began to dominate this job, white male flight attendants were assumed to be gay. This association shaped labor organizing as the job slid into a low-wage service one—and this job influenced how being gay is defined.

Anne Balay, Steel Closets: Voices of Gay, Lesbian, and Transgender Steelworkers (North Carolina, 2014) and Semi Queer: Inside the World of Gay, Trans, and Black Truck Drivers (North Carolina, 2018). These are by me. One reason that queer liberation and class struggle don’t seem to overlap much is that social structures of capitalism, white supremacy, and heterosexual norms embed themselves in our consciousness and become invisible.

Wishing that wasn’t so or denying it doesn’t change anything. But stories of how complicated and imperfect people come to understand their experience within these structures can open up paths of resistance. And they’re fun, which also helps.

My oral histories weave together stories that queer workers have told me as a means to understand how blue-collar work affects their lives. The steelworkers and truck drivers I met demonstrate that their work and their queerness aren’t separate—that each puts pressure on the other and makes the other possible and lively. These books are packed with details about the job, descriptions of how geography and history matter, plenty of sex, and queer folks expanding what we can do and be.

Books about being gay that say something important about working.

Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy and Madeline E. Davis, Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community (Routledge, 1993). This book started it all: it’s an oral history of lesbians in Buffalo and it’s packed with fascinating stories and thoughtful analysis. Though Kennedy and Davis focus on social worlds—bars, house parties—work comes up lots.

In the first half of the 20th century, Buffalo was a steel town. Job selection was defined by race and by how workers presented their gender to the world—meaning that butch women worked in industry and wore uniforms.

While we now understand lesbianism centrally as same-sex desire, it used to manifest mostly as looking and acting masculine. Kennedy and Davis locate this shift mostly in the 1950s, and it had everything to do with the work options and cultures available to queer women.

Marlon Bailey, Butch Queens Up in Pumps: Gender, Performance, and Ballroom Culture in Detroit (University of Michigan, 2013). Detroit in the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s was not worlds away from Buffalo. The Great Migration and the availability of manufacturing jobs with good unions meant prosperity for many Black workers. Bailey argues that this shaped Black families and genders—with gender operating not as a fixed quality but as a behavior whose meanings could shift in different places and times.

After deindustrialization, jobs evaporated but the new gender roles remained, and Bailey focuses on how ballroom culture adapted these roles to accommodate the only work available. People move in and out of service jobs, sustain a black market, and provide care for each other via “kin labor,” all of which enable a parallel economy and transform what labor and queer community mean. Care is queer work, and queer survival is labor.

Ryan Patrick Murphy, Deregulating Desire: Flight Attendant Activism, Family Politics, and Workplace Justice (Temple, 2016). Unions, according to Murphy, are the best grounds from which to critique both the conservative emphasis on family values and the neoliberal reliance on individual advancement and hard work. Organized labor wants us to work less, and still have money enough to be independently self-sustaining without that whole boring domestic routine.

Flight attendants—often single, not anchored to a house, and gay—critiqued the link between the nuclear family and jobs. There’s no such thing as a “working family” (we get hired as individuals, not family units) and the popular reliance on that trope serves to isolate workers by linking them to their families rather than their co-workers. Union logic, on the other hand, has workers standing together, supporting each other.

The rhetorical shift away from this solidarity hurts all workers, but queer ones are more likely to notice it because (in spite of the best intentions of groups like the Human Rights Campaign) we often spurn traditional family structures and so don’t fall for this drivel. Murphy thus wants unions to follow the lead of their queer members, emphasizing “work family,” fun, and free time rather than prioritizing after-work family commitments.

Books about working that say something important about being gay.

Jane Latour, Sisters in the Brotherhoods: Working Women Organizing for Equality in New York City (Palgrave, 1258). There’s a handful of books that describe the struggles women had breaking into unions in the 20th century. Of these, the only writer who names and analyzes the central role of lesbians is Latour.

She bases her book on oral histories of the women who broke into trades such as firefighting, carpentry, and construction. Latour explains how their unions’ response to them was affected by their sexuality, and how being lesbian encouraged them to seek out work in the trades to start with. The stories highlight how unions, while not necessarily welcoming to queer workers, are our best hope for workplace protections—since discrimination laws didn’t extend to sexual orientation (which may change based on last year’s Supreme Court decision) but union solidarity extends to all workers, even queer ones.

Matt Brim, Poor Queer Studies: Confronting Elitism in the University (Duke, 2020). Can a book about institutions of higher ed and the professors who work there be about the working class? I was convinced on page 22, where Brim names his salary. Even then, what matters is not the figure named, but Brim’s sense that this data needs to be a part of a conversation about the elite production of knowledge.

This book reveals how the academic discipline of queer theory originated and was developed within elite institutions, and turns its attention to what’s often left out of that theory: stories of queer collective resistance, including on campus.

Queerness enables coalitions: Brim locates queerness in stories of movement, migration, and solidarity. Union organizing is one expression of that queer solidarity. It’s queer trouble.

Anne Balay organizes adjunct faculty in St. Louis. She is the author of the two books described above, and of numerous articles. If you know of books on this topic she has not included, she is eager to learn of them. Send titles to annegbalay[at]gmail[dot]com.