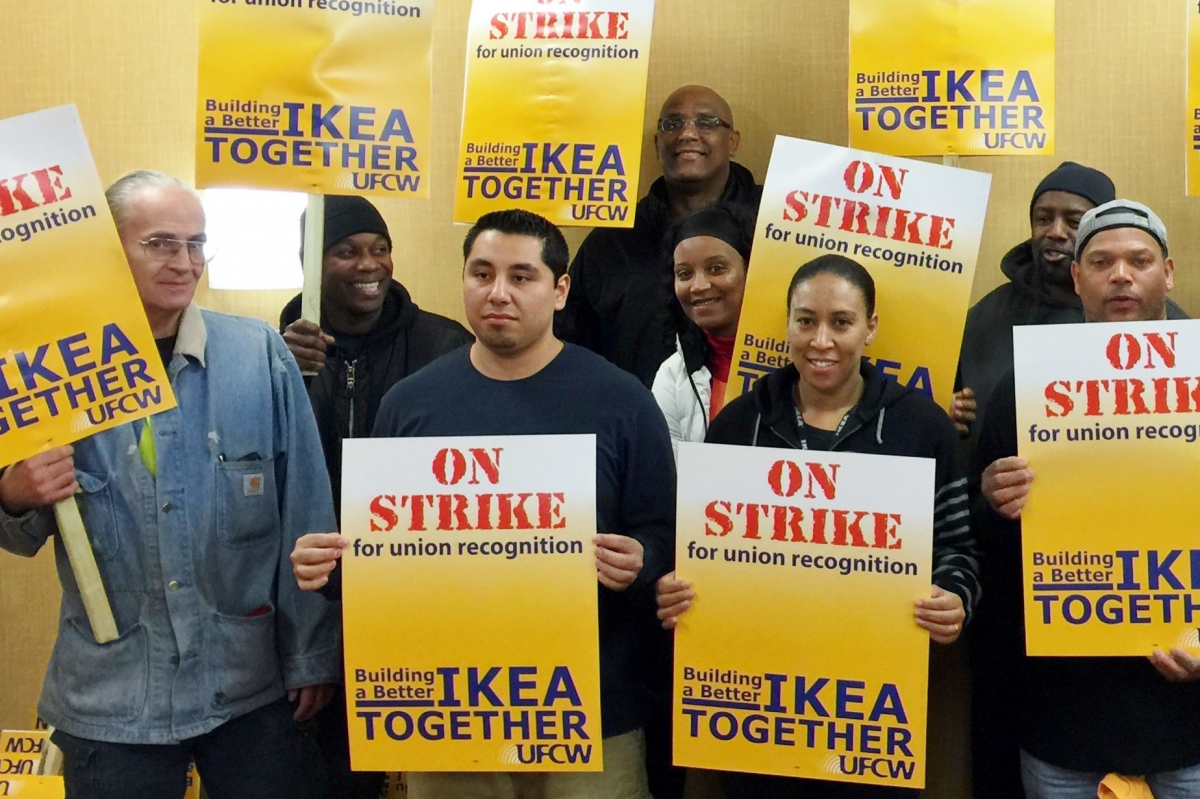

This morning in Stoughton, Massachusetts, 14 IKEA workers walked out on a one-day strike—the first ever in the furniture giant’s U.S. stores.

“I’m fighting for my rights,” said striker Veronica Cabral, a 36-year-old single mother and immigrant from Cape Verde. “I want better for me, my family, and my co-workers.”

The union would consist of the 32 people who work in the “Goods Flow In” department, where workers receive shipments and stock the store. Last week they delivered a petition demanding union recognition, signed by 75 percent of the department.

They would form a so-called “micro-bargaining unit,” affiliated with the Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW)—following in the footsteps of retail workers at Target and Macy’s who have formed small bargaining units since a 2011 National Labor Relations Board decision, Specialty Healthcare, opened the door.

“It’s been a long fight. Three years ago we started with the Teamsters and we had 70 percent since then,” said Chris DeAngelo, 45, who’s worked at the store for eight years. “What changed is that we can have a micro-unit now.”

Ultimately, DeAngelo said, “our plan is to unionize the whole store. But it is difficult with the different shifts and different parts of the store. We are working up to getting everyone else.”

Fears and Reprisals

The same day the workers delivered their petition, Democratic presidential candidates Martin O’Malley and Bernie Sanders sent letters to IKEA U.S. President Lars Peterson, urging the company to recognize the union.

Sanders castigated the company for “blatant intimidation coupled with subtle yet effective psychological warfare against workers who wish to unionize.”

“We had a ‘code of conduct’ training that seemed routine until we were asked to go around the room and talk about our union sympathies,” said machine operator Shawn Morrison, 28. “That was routine, just a part of the training, until someone called it out. Another time the store manager called us up to the H.R. office. He dropped union literature on the table and asked us how we felt about it.”

“IKEA has team leaders on the floor trying to scare everyone about what will happen if there is a union,” Cabral said. “They tell us we will be fired.” She’s been urging her co-workers not to get scared off.

Unionizing IKEA in the U.S.

Three hundred workers at the IKEA factory in Danville, Virginia, voted overwhelmingly in 2011 to join the Machinists—despite the efforts of union-busting law firm Jackson Lewis—and ratified a first contract that same year.

Before the union drive, the plant’s starting wage was $8 an hour—in contrast to a $19 starting wage and five weeks’ paid vacation at the company’s Swedish factories. Under a humiliating discipline system, workers accumulated discipline points for using the restroom without permission or for leaving work to take a family member to the emergency room. They also complained of favoritism, a lack of training, and loads of forced overtime.

Workers at three IKEA warehouses—in Perryville, Maryland; Savannah, Georgia; and Westhampton, New Jersey—have since joined the Machinists too, and in 2013 workers at an IKEA warehouse in Frederickson, Washington, joined Teamsters Local 117.

—Dan DiMaggio

But managers have begun targeting pro-union employees for arbitrary discipline—which made the petition and strike urgent, workers said.

“We couldn’t wait any longer. We had to make some sort of decision,” DeAngelo said. “We know that we all have targets painted on us, especially those of us who have been there longer and are making more than the new recruits.

“This store has been open 10 years and I have been there eight, and there has been no improvement. There is all this tension, all this instability, all this insecurity. You never know when the other shoe is about to drop.”

At the end of their shift November 14, workers in the Goods Flow In department were called together to hear the store manager and head of H.R. give the company’s official response to their petition.

The letter from IKEA management said that “by recognizing the UFCW as the representative, we would be taking away the chance for each individual co-worker to make a choice” and that a secret-ballot election supervised by the Labor Board would be “more consistent with the approach we have taken in our U.S. distribution centers.”

Workers were livid. “Their excuse for denying the petition is ridiculous and disrespectful to the 75 percent of people who signed their names,” DeAngelo said. “That is why we are going on strike. It is a slap in the face. It is absolutely disgusting.”

The American Model

IKEA, a Swedish company headquartered in the Netherlands, touts its commitment to social responsibility and worker rights. In Europe its retail workers are overwhelmingly unionized.

But like pro-union workers in Volkswagen’s Chattanooga, Tennessee, plant, the Stoughton IKEA workers are realizing that their employer is not so much a socially responsible European company doing business in the U.S. as an American-style company that just happens to be headquartered in Europe.

“The American Model—that is what they are calling it,” said DeAngelo. He points to IKEA’s hiring of the notorious anti-union law firm Jackson Lewis to bust the organizing campaign. “A truly socially responsible company wouldn’t do that.”

Morrison traveled to Milan, Italy, last month to attend the IKEA Global Alliance meeting, which brings together unions representing the company’s retail and warehouse workers from all over the world.

“One of the things that our European co-workers felt was that the company was shifting more and more towards the American model and that their labor unions would be in danger,” he said.

“In Europe they kind of believe that the United States does not want unions,” Morrison said. “Europe has gone such a long time thinking that the U.S. is just a barren wasteland of union activity, but we are showing them that that is not true.”

Despite IKEA’s opposition, he said, “we are serious about having a union. And if it does come to an election, we will vote a majority yes.”

Chris Brooks is a graduate student in the labor studies program at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and an organizer living in Chattanooga.