Members Demand a Voice in Their Unions' Presidential Endorsements

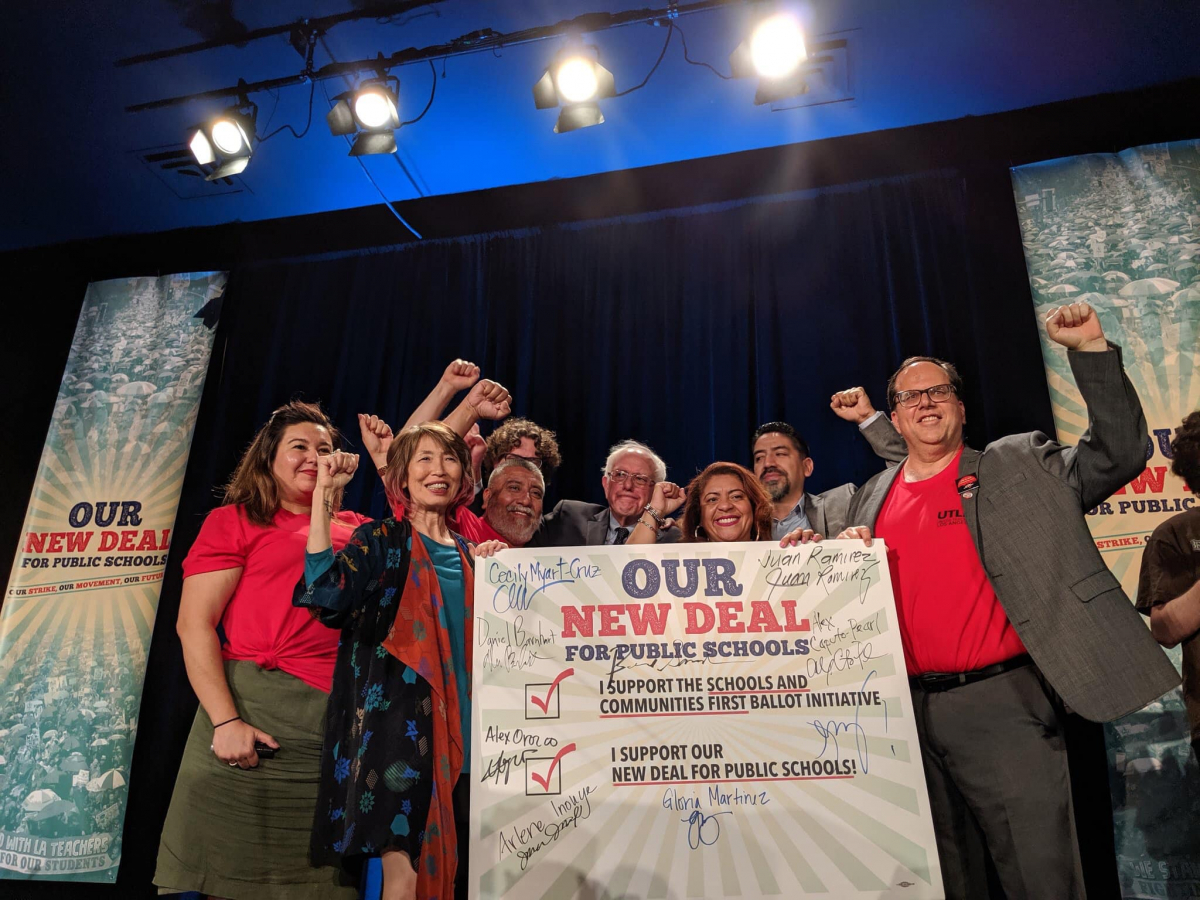

Over the summer Bernie Sanders spoke at the convention of the AFT’s second-largest local, 34,000-member United Teachers Los Angeles.In September, the union kicked off a process for members to weigh a possible Sanders endorsement. Photo: UTLA

As the first union endorsements for president trickle in, union members and leaders are fighting to shape both the outcomes and the process of how endorsements are made.

Four years ago, by September 2015, seven national unions had made endorsements in the Democratic primary, though the AFL-CIO had requested that affiliates delay action.

Six—the Teachers (AFT), Machinists, Roofers, Plumbers, Bricklayers, and Carpenters—had endorsed Hillary Clinton. National Nurses United had endorsed Bernie Sanders.

This time around, with a far more crowded Democratic primary field, only two unions have weighed in thus far. In April, the Fire Fighters endorsed Joe Biden, and in August, the United Electrical Workers (UE) backed Sanders. In September the International Union of Police Associations, an AFL-CIO affiliate of about 100,000, endorsed Donald Trump.

On the local and state level the Hotel Trades Council, Local 6 of UNITE HERE in New York City, endorsed Mayor Bill de Blasio for president (he has since dropped out), while Sanders got Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Local 230 in Ottumwa, Iowa, Roofers Local 36 in Los Angeles, and the Pennsylvania Federation of the Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way Employees, which called on its international, the Teamsters, to also endorse Sanders.

WHO DECIDES?

Several unions have made a point of their revised endorsement processes, in response to some members’ dissatisfaction with procedures in 2016. The AFT and the Machinists both faced blowback from members after their early endorsements of Clinton.

In a video and letter to members, Machinists President Bob Martinez announced that an independent firm will conduct a series of internal polls and a membership-wide vote to nominate a Democrat and a Republican. Then local and state elected leaders will vote between the two.

The AFT’s process is less clear-cut. A new website, AFTVotes.org, declares the union’s commitment to “increased member engagement, input, and feedback” and to “ensure transparency,” but with endorsement ultimately still resting with the Executive Council and no mention of a membership vote.

Some working teachers, like Russell Weiss-Irwin in Boston, are organizing against this process. A Sanders supporter since 2015, Weiss-Irwin tried to get his union (he was then a member of Service Employees 175 in New Jersey) to endorse Sanders, but by the time he started organizing, he says, SEIU had endorsed Clinton and “it was a done deal.”

This time he got started early, going to a Young People’s Caucus of the Boston Teachers Union to find like-minded people. He penned a petition to the national AFT that calls for one-member one-vote on endorsement. Several hundred AFT members have signed and a handful of locals, mostly at community colleges, have passed resolutions.

A similar petition is circulating in the National Education Association, and delegates brought such a motion to the floor of the union’s annual meeting this summer, though it was defeated.

Over the summer Sanders spoke at the convention of the AFT’s second-largest local, 34,000-member United Teachers Los Angeles. In the days afterward, the L.A. school district was among the top 10 employers, nationally, where Sanders donors worked. (Donors to campaigns must report who their employer is, and ranked by profession, teachers are Sanders’s top donors.)

In September, UTLA kicked off a process for members to weigh a possible Sanders endorsement. Sanders and the union have already endorsed each other’s education plans. All those attending the union’s area meetings November 13 will hold an advisory vote on whether to endorse Sanders.

At the National Union of Healthcare Workers leadership conference in September, delegates watched videos of candidates seeking their endorsement. NUHW has a one-member, one-vote process, with voting links sent to members via email and text; they may vote for up to three candidates. The executive board will interpret the vote.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE) members have started their own petition calling for endorsement to be based on a membership vote. David McMahon, a shop craftsman in Local 52 in the Philadelphia area, said, “Recently, our union president called for more engagement from the members. So we were like, here it is.”

Though the petition is explicitly nonpartisan, McMahon himself, like Weiss-Irwin, is motivated by his support for Sanders. “There’s no one more pro-worker than Bernie Sanders,” he argues, “and in addition to showing up on the picket lines, he’s putting together, especially in his Workplace Democracy Plan, such a comprehensive set of ideas that are going to strengthen the labor movement going forward. We could see material gains for working people that we haven’t seen in generations.”

In 2016, the Communications Workers and the Steelworkers both held membership votes, but their 2020 procedures remain to be determined.

A handful of candidates visited the United Auto Workers’ picket lines at GM plants. Sanders also went to the September rally held by the Chicago Teachers Union to promote its strike vote.

LABOR FOR BERNIE

By far the most organized effort among union members has been Labor for Bernie, an independent grassroots network that originated in 2015. It was relaunched in May with a letter from Chuck Jones, the former Steelworkers Local 1999 president who gained fame for sparring with Trump at Carrier Corporation in Indiana.

The network has formed active groups in Los Angeles, the Bay Area, Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and other cities. They have marched in Labor Day parades, sought to speak at union meetings, and held debate watch parties. The national group is seeking signatures on a pledge to vote for Sanders in the primaries.

“Labor for Bernie is unique because it has an asset that all the other campaigns would covet: thousands of dedicated rank-and-file labor supporters who are members of almost every national union," said Rand Wilson, an SEIU staffer in Boston.

Barbara Ingalls designed a Labor for Bernie banner that has been carried in two Detroit marches, one for Labor Day and one calling for a Green New Deal at the Democratic candidates’ debate in July—receiving lots of snapshots and social media each time. “It’s clear the Bernie supporters really value union participation,” Ingalls said.

Labor for Bernie has been particularly active in Philadelphia. Paul Prescod, a teacher, says the focus has been on two levels: building support among local union leaders to involve members in the 2020 discussion and organizing rank and filers to push their unions to a democratic endorsement process.

At organizing meetings, Prescod says, “we have people break out by union or by sector. I think it looks differently in every local. Some might feel like they have a realistic chance of getting an endorsement, some it’s more about just building a network.”

Labor for Bernie activists helped get the Philadelphia AFL-CIO to hold a “Workers’ Presidential Summit” September 17. Prescod said the event, attended by hundreds, had “a sleepy feeling,” including when Joe Biden spoke, till Sanders was introduced, which set off cheers.

Other contenders were de Blasio, Amy Klobuchar, Andrew Yang, Tim Ryan, and Tom Steyer.

When a Libertarian Roofers member interrupted Sanders’s talk with insults, he was drowned out by chants of “Bernie, Bernie, Bernie!” “He was, like, the show,” Prescod said. “Every time he made a big point—the Workplace Democracy Act, the Green New Deal, health care—people would cheer.”

Jonah Furman is an educational aide and union activist in Washington, D.C. and a member of AFSCME Local 2921.

Comments

Democratic Values in NUHW Endorsements

I'm so glad that workers are demanding a say in their endorsements. I used to be a part of SEIU and was so angry when they endored without any member input. I'm proud to now be a part of NUHW, which did a full membership-wide vote for our 2020 presidential endorsement (we also had a democratic process in 2016, when our stewards statewide voted for our endorsement). Here are the details: https://nuhw.org/nuhw-members-endorse-warren-sanders-president/