‘We’re Sick of Giving Away Our Future’: An Interview with Kellogg Strike Leaders

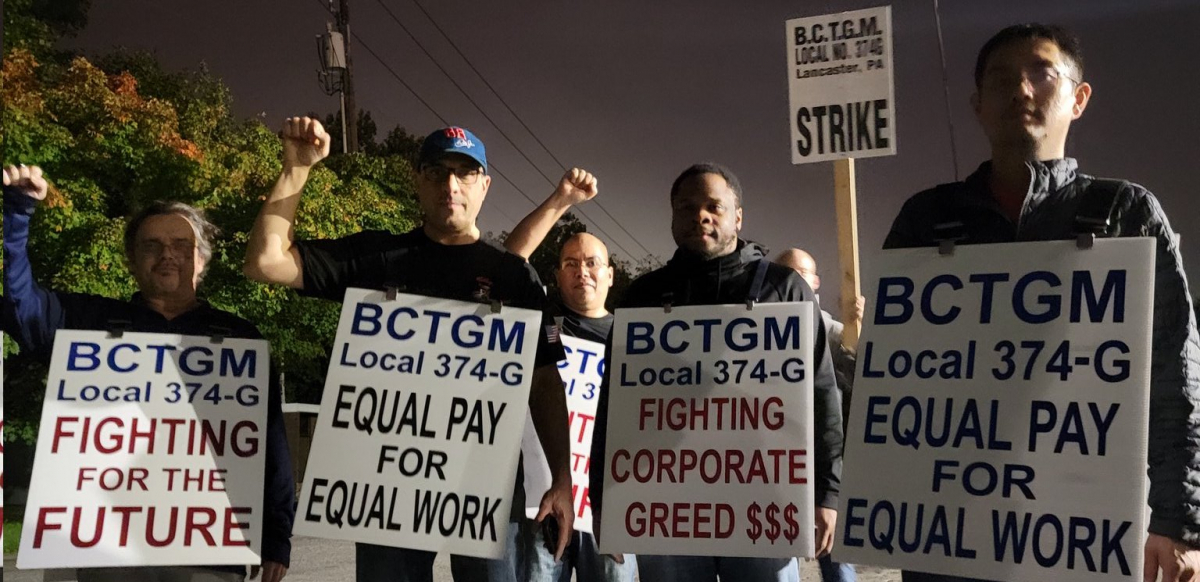

Workers outside Kellogg's Lancaster, Pennsylvania factory are picketing as part of an ongoing nationwide strike against the cereal maker. Below, Labor Notes speaks to two local union officials from Battle Creek, Michigan. Photo: Anthony Downing, cropped from original

Just after midnight October 5, workers at all four of Kellogg’s “ready-to-eat cereal” plants went on strike. Bakery Workers (BCTGM) Local 3G represents the 395 workers at the flagship plant in Battle Creek, Michigan. Labor Notes spoke with Local 3G President Trevor Bidelman and Vice President Paul Walling. Both men have been at the plant since the mid-2000s, and are still working members. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Labor Notes: Why are you on strike?

Trevor Bidelman: Well, we’re here for the future. The message here is, “The future’s not for sale.” [Kellogg wants] a permanent two-tier benefit system; the current people that work here will lose their path to get to the benefits and the pension. They’re trying to take the path away [for current employees], and for all the new hires.

Paul Walling: We have a 70/30 split, 70 percent seasoned employees and a 30 percent transitional workforce. They like to call us “legacy employees.” I just don’t like that word. I’m not legacy. I use “seasoned.” I use “long-term” employees.

Bidelman: Currently that 30 percent of the workforce that’s second-tier, they have a transition process: as one top-tier person retires, they get to come into [the top tier]. The company is eliminating that transition for the current employees.

What’s the difference between being a top-tier “legacy” worker, and a bottom-tier “transitional” worker?

Bidelman: The pension and the health care are the huge differences. Even the pay gap is huge. The pay gap between tiers is $12 an hour.

Walling: They also have different paid holidays than we do. They get, I believe, four less paid holidays than we do. Their benefit level is substantially lower than ours when you start talking about health care, pensions, paid holidays, vacation. They’re capped at three paid weeks. We [receive] six once we get our time in. Their benefit level is, I would say, half of what ours is.

Second tier is missing out—they’re matching your 401(k), but you’re not even getting a pension. Their health care is a two-tier health care; theirs is out of pocket, 80/20 premiums. No retiree health care.

Was Kellogg always two-tier?

Bidelman: So it used to just be you had to do a wage progression, and after four years, you’re at top rate. You started off fully benefited and fully pensioned from the day that you were hired. It was just a wage progression.

That changed, at least in our plant, around the mid-1990s, when they brought in this temporary workforce they called the “casual” workforce. This is where [we see] the seeding of the massive distrust we have with the company. They brought that in under the guise of, “We're going to bring guys in on the weekend to come in and clean a little.” It was sold as “Oh, these people might work three, maybe four, days a week.”

It wasn’t until the early 2000s that they started expanding the use of the casuals. I was actually a casual myself; I was casual May 2004 until December 2005. As far as forced overtime, when I was a casual I would work four to five 16-hour shifts every week. I worked 116 days in a row.

By 2011, when I went to the contract table to fight over this workforce, we had around 70 casual employees working 3,000 hours a year.

They were abusing them so bad. They locked [workers at the Memphis factory] out in 2013 for 10 months. The company wanted to go full casual.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

2015 is when we got to the transitional piece, which got all these people at least seniority. We had casuals for eight years as casuals.

Walling: [Today] the most-senior [second-tier workers] have been [here for] five years. [But] it could be five years, could be 15 years. [That is, workers will be stuck on the bottom tier for however long it takes to move out of the bottom 30 percent of the workforce by seniority, which defines the tiers. -Editors] They want it to be never. There will be no path.

Bidelman: We also have the issue of job security. At one point our plant alone had 4,000 people and [now] we’re down to 395. They’ve been shipping work to Mexico since the late 1990s. They've made it very clear that’s what they’re going to do.

Walling: They keep sliding the numbers. The 70 percent [top-tier employees] is based on a plant level.

So top-tier employees can retire, but no bottom-tier employees get converted to the top tier if Kellogg cuts jobs, because the formula is based on a percentage of the total number of jobs in the plant.

Bidelman: When you figure after what we’ve just been through in the pandemic—we were hailed as heroes. Only takes 11 months to change that H to a Z, heroes to zeros. They just announced they’re going to take three lines out of the plant and cut 174 of 395 union jobs.

What has it been like working through the pandemic?

Bidelman: It’s hard. They started off, “You’re heroes, you’re essential.”The world had stopped except for us; we were the only people on the road, almost. Of 325 members we have, we had over 70 positive cases in the plant. You heard about your friends getting sick; you don’t know if you’re gonna get sick. You’re going to work every day in fear. They’re so short-staffed that every time the phone rings, they’re forcing people over [i.e. forcing people to work overtime -Eds]. Sixteen-hour shifts. [Workers are] beat down, frustrated, and this is it. They’re over it.

How do you get top-tier employees to strike for bottom-tier employees? What stops them from saying, “Well, I’ve got mine”?

Walling: You have to understand that if we don’t fight for these folks today, the reality of it is, one day they will outnumber us. So when that day comes, am I going to be right at the retirement door, and then have everything stripped from me? So that’s one mentality behind it.

The second mentality behind it is, a lot of my people are just sick of giving away our future. We’re tired of these companies coming in and just wanting a little more. Wanting a little more. And their profits keep going up. And their profits keep going up. But they want a little more.

I used to say back in the day, when baby boomers were coming through, companies cared for them. There were long-term jobs then. But now you have millennials or Gen Xers who understand, “I might have 10 jobs in my lifetime.” So a long-term employment for us is five to 10 years at best. Far as I’m concerned the companies are running away to the bank and just cashing out.

Bidelman: They want to take the cost-of-living provision away from us. They want to make us use vacation up before we use [Family and Medical Leave Act leave], attacking people with health conditions. They’re trying to make it so you have to work each day on either side of a holiday to get holiday pay. How much more do you want?

You can donate to the Kellogg workers’ strike funds here.