A History of America in Ten Strikes

Thanks so much for the review, Dave, will get the book asap. Sounds grrreat. Tim Sheard, Hard Ball Press

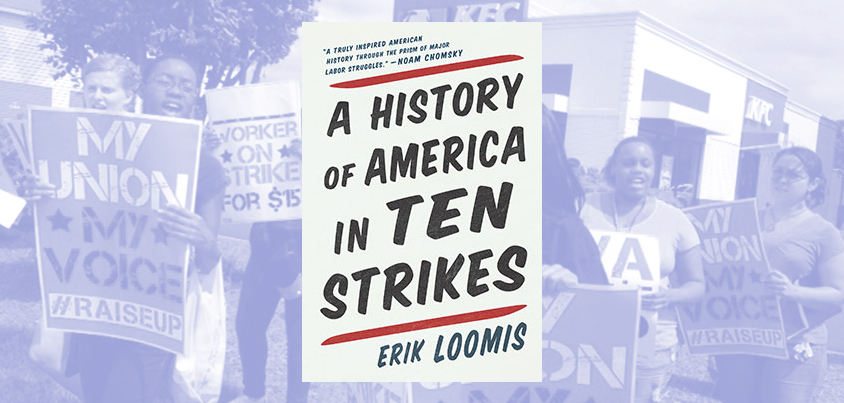

A History of America in Ten Strikes, by Erik Loomis. 2018, The New Press, 301pp. Photo: AFL-CIO (CC BY 2.0)

At first glance, one might be forgiven for thinking that A History of America in Ten Strikes is some kind of social-media-driven “listicle” book. Author Erik Loomis, a historian and union member at the University of Rhode Island, is a well-known blogger, and his excellent Twitter threads on labor history show he’s digitally savvy.

But this isn’t a best-of book. Indeed, it’s not even really a book about strikes. The book does include great stories about strikes, from better-known examples like the Flint sit-down strike of 1937 and the PATCO strike of 1981 to lesser-known ones like the Pennsylvania anthracite strike of 1902 and the Oakland general strike of 1946. But it truly isn’t about strikes. Instead, exactly as the title says, it’s a history of the country told through the lens of labor strife. It’s an ambitious goal, and in this accessible and engaging book Loomis lives up to it.

Even among folks in the labor movement, who have seen the many ways that working people have so frequently been exploited, the prevailing myth of the United States as a land of steady progress and improvement is tough to shake. It’s still a radical idea that conflict between workers and bosses is at the heart of America, rather than an aberration.

But Loomis makes a convincing case: at every stage in American history, there are strikes to illuminate how our nation has developed. While it is tempting to second-guess his choices—why isn’t the Memphis sanitation workers strike of 1968 included? Why no strikes from the period of labor strife immediately following the First World War?—such arguing is beside the point. There are dozens, hundreds, thousands of strikes that could have been used to frame the history of the country.

Each chapter is organized around a single strike, which Loomis sets in the context of other developments—political, social, cultural—that help explain how it came about and what that strike tells us about America. That context gets more attention than the individual strikes, and rightly so. It’s the richness of the context that makes this book so fascinating.

Many academic historians make the mistake of taking material better suited for a 30-page article and turning it into a 300-page book. Loomis takes the opposite, and better, approach. Each of his chapters could easily be expanded into a book of its own. Stories that could have gone on for pages are compressed into a few spare sentences. Each chapter references many other strikes—so in fact, Memphis and Matewan and many more are covered.

The chapters are self-contained enough to be used on their own in union trainings or reading groups. The price of the book is worth it for the extensive and nearly exhaustive bibliography alone. Readers—like this reviewer—who want more will know where to go.

In a book with many important ideas and themes, two stand out. First, Loomis shows time and again that any attempt to separate issues of economics from issues of “identity” is ridiculous.

From the very beginning of American history, sexism, racism, and anti-immigrant sentiments have been inseparably tied to the types of work people do and the strength (or weakness) of worker power. Bosses routinely used prejudice as a tool to keep workers at each other’s throats. All too often, workers played along.

While Loomis is too careful a historian to draw stark binaries, in case after case it was white working men who were most ready to sell others out to keep their own privileges.

The biggest strike in American history—the general strike by slaves in the South during the Civil War—was initially opposed by President Abraham Lincoln. Southern whites had convinced themselves that slaves were happy with their lives, and were genuinely surprised when slaves took advantage of the chaos of the war to escape, engage in work slowdowns, or in other ways suspend their labor. Lincoln initially reversed a military order freeing slaves who escaped to Union lines, but as the general strike spread in scope and impact, Lincoln changed his mind.

The biggest labor organization of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the American Federation of Labor, survived by making sure that its jobs were kept in the hands of white men only. The first significant piece of successful legislation supported by unions was the Chinese Exclusion Act, setting an anti-immigrant tone that still pervades too many unions. As labor’s power reached its zenith at the end of the Second World War, unions expended considerable resources to push out women and people of color and restore jobs to white men.

It’s not all discouraging, though. Loomis also shows those moments when solidarity across lines of race, gender, and nationality did amazing things for workers.

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

The success of the Bread and Roses strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, depended on the union’s conscious efforts to organize in multiple languages and treat all workers as equals. Unfortunately, the Industrial Workers of the World didn’t emphasize developing sustainable institutions, and after the union’s high-profile, charismatic leaders left town, the movement collapsed.

The workers at Lordstown’s General Motors plant in 1972 showed powerful unity across racial lines (still too rare a phenomenon) when they struck over the lack of meaning in their jobs. The failure of the Auto Workers and other unions to harness that spirit is one of many intriguing what-ifs in the book.

Success, as with the Justice for Janitors strikes of the 1990s, is only possible when unions bring workers together regardless of their backgrounds.

The second theme Loomis emphasizes is that workers’ success in taking on bosses often depends on the role of government.

For all the tactical genius behind the sit-down strike that autoworkers so successfully organized in Flint in the winter of 1936-37, the strike would have likely ended in blood and failure if Michigan’s new labor-friendly governor hadn’t used the National Guard to stop the company forcing the strikers out.

A useful contrast Loomis draws is with the Memorial Day massacre, just a few months after the victory in Flint, when 10 striking Chicago steelworkers were killed by police who were openly on the side of management. Organizing the steel industry was set back years by such violence—the National Labor Relations Act was worth nothing more than the paper it was printed on when the government was prepared to tolerate employers violating the law.

From the very beginning of organized labor action in the United States, as Loomis shows in his opening chapter on the Lowell Mill strikes of the 1830s and 1840s, bosses and corporations used courts, legislatures, and police forces to control and crush labor actions. Only when government leaned in the direction of unions did worker power, however strong, prevail.

When Ronald Reagan fired the air traffic controllers in 1981, his action sent a signal to employers that the federal government’s four-decade experiment of supporting labor rights was at an end, and what Loomis rightfully calls a New Gilded Age has been the consequence.

While the past year has seen exciting bursts of union power in the face of government resistance, kicked off by the heroic West Virginia teachers, Loomis’ argument suggests that the staying power of such efforts depend on whether such displays of solidarity are enough to dampen government opposition.

Today, even supposedly pro-union political leaders are reluctant to use the machinery of the state to help workers in direct conflict with employers. Rather than relying on politicians, it’s going to take a resurgence of organizing from below, following the example of teachers across the country, to change the balance of power in favor of working people. At the same time, A History of America in Ten Strikes shows that without the support of government, solidarity alone often won’t be enough for a lasting victory.

With a consequential election just a week away, this lesson is all too timely.

Dave Kamper is a labor organizer in Minnesota. He can be reached at dskamper[at]hotmail[dot]com, and followed via Twitter @dskamper.

Thanks so much for the review, Dave, will get the book asap. Sounds grrreat. Tim Sheard, Hard Ball Press