Transit Workers Look to Bust the Austerity Box

Like public sector workers everywhere, New York City’s transit workers face a withering attack on our compensation and our collective organization.

As contract talks continue between Transport Workers Union Local 100 and the Metropolitan Transit Authority, small pay raises in the fourth and fifth years of a proposed deal are tossed about in the press.

But between giant health care cost increases, full-time job cuts, and workplace destabilization, transit workers would go backwards.

The contract, covering 35,000 subway and bus workers, expired January 15. Union negotiators, led by Local 100 President John Samuelsen, have vowed not to accept takeaways.

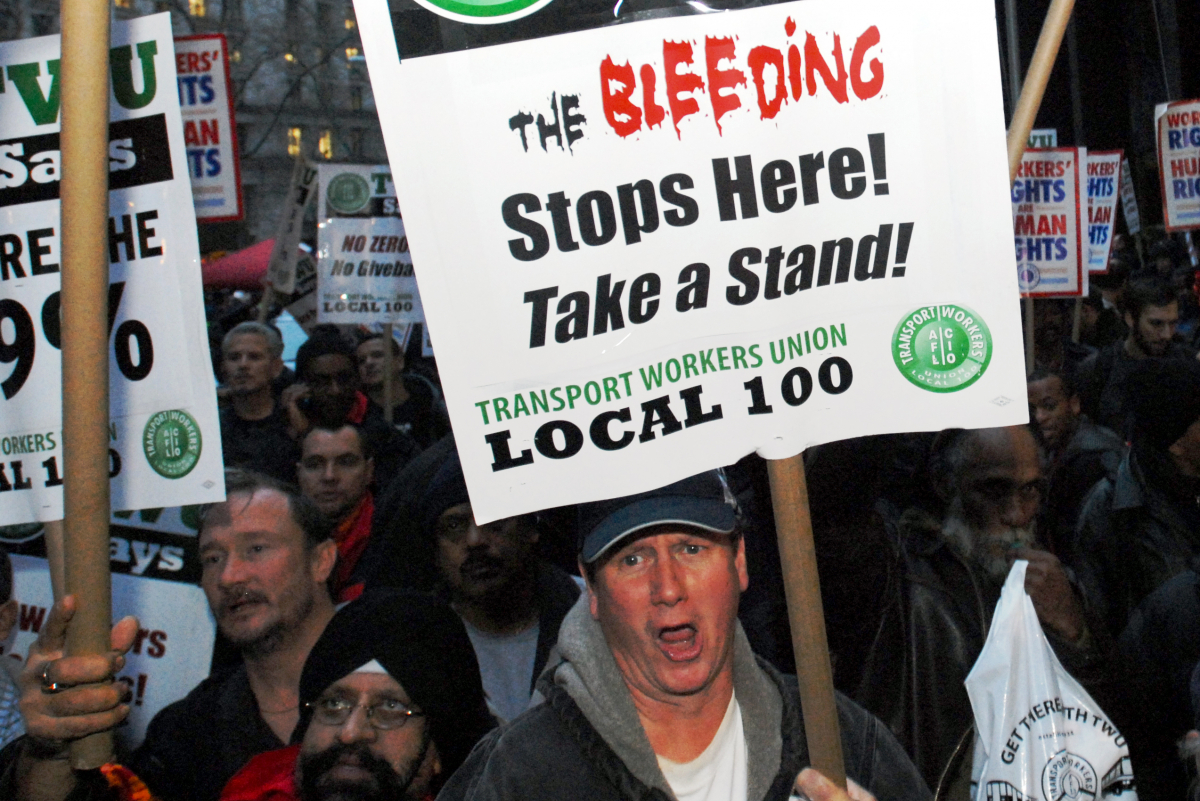

The union has rallied for months, and a January 15 event outside the talks brought a broad array of community and environmental groups, and local politicians, along with members of Occupy Wall Street.

The MTA is proposing work rule changes that would explosively expand the part-time workforce: 20 percent of workers would no longer be guaranteed an eight-hour day. TWU opposes the bid because more part-time workers would reduce the union’s cohesion and ability to fight back.

Management also wants to chop compensation by eliminating pay for the time workers must travel between work locations, which can stretch over two hours in the giant metropolis.

But the biggest cutback would come from a drastic increase in what workers pay for health insurance. Current proposals would cut net pay by a double-digit percentage.

In preparing to demand these cuts, management’s first action was to shut the safety valve that in past recessions had absorbed workers displaced from other MTA departments and city agencies: the station booths. In recent years the MTA has laid off almost 500 station agents and closed booths.

Management’s Foot in the Door

The state’s public employment relations board called the workforce that runs public transportation in New York City the most efficient and productive urban mass transit workforce in the U.S.

Labor costs are low as a percentage of operating costs, yet management demands more sacrifice from transit workers because tight budgets are a permanent and advancing dynamic for the public sector everywhere. Experience shows that when public employees sacrifice to meet budget requirements, they get only demands for more sacrifice.

New York state workers are witnessing an example of this dynamic. The Civil Service Employees Association and the Public Employees Federation accepted contracts last summer with cuts to health care and pensions and zero raises (though PEF dissidents led an initial rejection of the concessions).

Governor Andrew Cuomo is now demanding a sixth pension tier for future state employees, which would raise the retirement age and substitute a 401(k) for defined benefits. He claims a “life-long legacy” can no longer accompany public employment, despite a history among public workers of trading lower wages for better benefits.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Governments worldwide spend an ever-diminishing amount on all public services, as they cut taxes to business and wealthy individuals. This has been especially true for New York’s transit system.

State funding for MTA has suffered from decades of thievery and neglect by hostile politicians who have repeatedly raided dedicated transit dollars, forcing the MTA to borrow huge sums to finance its construction projects. One-fifth of every transit dollar now goes to Wall Street financiers, thanks to the bipartisan attack.

Most recently, Democratic Governor Cuomo and Republican leaders agreed to cut a tax worth $320 million a year to the MTA, thus setting up the agency to swell its debt load to almost $42 billion this year. The eye-popping debt again causes management to demand workers pay the price for politicians’ neglect.

The Long Arm of Austerity

The conditions for austerity began long ago.

In the early 1970s, corporations established new think tanks to develop long-term strategies for the transfer of wealth upward and the disintegration of worker organization and government oversight. Led by the Business Roundtable, they devised rationales to end regulation, crush unions, promulgate free trade, and impose austerity.

When public debt began spiraling in the stagflating ’70s, business was well-positioned to take direct control and roll back the public sector. In New York City this was done through the Municipal Assistance Corporation, a committee of bankers that oversaw all financial decisions by elected officials and city agencies from 1976 to 1982.

Because both political parties participated, business has since then dictated in practice without having to exercise direct control.

Resistance

In the second half of the 1970s, the city closed 13 hospitals and many libraries, firehouses, and other city services. Tuition was imposed at the City University of New York, where education had been free for more than a century. Tens of thousands of jobs were cut in every agency and the remaining workers saw no raises.

The greatest resistance to those attacks came from community organizations, through protests and occupations at hospitals, firehouses, and colleges. While public sector union locals offered some support, union officials treated the crisis as a short-term budget debacle, rather than the dawning of a new day.

The exception was TWU Local 100, which struck victoriously in 1980. A rank-and-file movement among its members was fed up with zero raises in 1976 and 1978 and calls for more sacrifice. The strike won 16 percent in raises over two years and a cost-of-living increase. It was the last settlement in which Local 100 made no concessions.

While unions, worker organizations, and working class communities are way behind the 1% in organization, we can give thanks to the new activists in the Occupy movements. We now have a much clearer idea of what the 1% are doing and an awareness of our shared struggles.

All government budgets represent a set of political decisions previously made. Those priorities can be changed, though it’s no easy task.

Tim Schermerhorn is a rank-and-file train operator and organizer in Local 100. He is a former vice president of the local and former vice chairman of train operators. Contact him at timtransit [at] yahoo [dot] com.