Not Words, But Action: Moranda Smith, Food and Tobacco Workers Local 22, and the Fight to Expand Democracy

This detail from the comic below recalls the remarkable 1943 strike at the giant R.J. Reynolds tobacco plant in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. One of the strikers, a sharecropper’s daughter named Moranda Smith, would later become the first Black woman in the national leadership of a U.S. union. Graphic: Annabelle Heckler

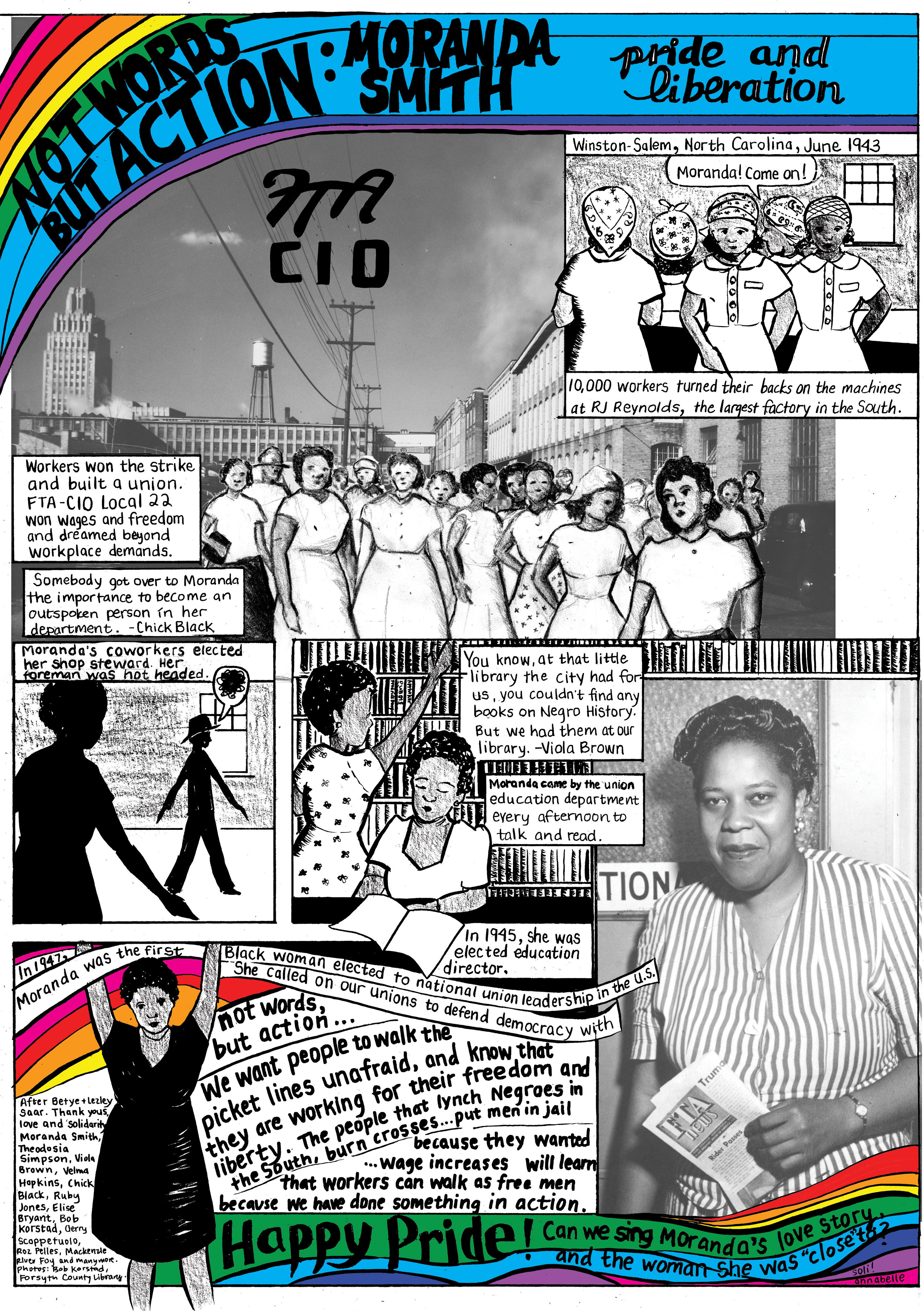

Comic: ‘Not Words, But Action: Moranda Smith, Pride and Liberation’

by Annabelle Heckler

We may never know how many LBGTQ+ workers there were leading our unions in the past, but we can be certain that they were there.

Annabelle Heckler’s new comic “Not Words, But Action: Moranda Smith, Pride and Liberation” remembers an R.J. Reynolds striker who went on to become a national leader of the militant Food, Tobacco, Agricultural, and Allied Workers. >Click the image to view the comic full-size.

See more of Annabelle Heckler's work at @annabelleheckler on Instagram.

June is Pride Month, which celebrates and commemorates the struggles of LGBTQ+ people for freedom. It is held in June to commemorate the Stonewall Riots, several days of protests that began on June 28, 1969, and launched the modern movement for LGBTQ+ rights.

This June also marks the 80th anniversary of a remarkable strike at the giant R.J. Reynolds tobacco plant in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, which established Local 22 of the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural, and Allied Workers (FTA). One of those strikers, a sharecropper’s daughter named Moranda Smith, would be elected to the national union’s executive committee three and a half years later, making her the first Black woman in the national leadership of a U.S. union.

While we don’t know how Smith described her identity or her intimate relationships, other Local 22 leaders described her as “close to” another woman leader in the local, and decades later, FTA organizer Ed McCrea told gay labor activist Gerry Scoppettuolo that Smith was “one of your people,” i.e. LGBTQ+.

HIDDEN HISTORY

The history of LGBTQ+ workers, especially before the 1970s, is largely hidden. Secrecy was often essential to their survival: those who were “out” risked being fired or harassed at work, ostracized, or subjected to violence.

Explicit protections against discrimination based on sexual orientation did not exist until LGBTQ+ workers and their co-workers began to organize to win them in union contracts and laws — something that was rare before the 1970s, and did not become widespread until the 1990s and later. Almost a third of U.S. states (and the federal government) still do not protect LGBTQ+ workers against discrimination at work.

LGBTQ+ workers have played crucial roles in building our labor movement, even if there are few traces of this in official archives (or those traces are hard to read). We know about Smith because McCrea met Scoppettuolo on a picket line in Nashville in 1990 during the Greyhound drivers’ strike.

We know about the militant history of the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union in fighting for gay rights because historian Allan Bérubé, who had heard “legends too outrageous to believe” about gay men who worked on big passenger ships in the 1930 and ’40s and were elected leaders of their union, was introduced to former MCS activist Stephen “Mickey” Blair in 1983.

We may never know how many LBGTQ+ workers there were leading our unions in the past, but we can be certain that they were there.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

It’s perhaps not surprising that both Smith and Blair were members of unions that practiced what we in the United Electrical Workers (UE) call “them and us unionism,” combining a commitment to aggressive struggle to improve our conditions with a commitment to uniting all workers.

In 1947, Smith gave a speech to the Congress of Industrial Organizations convention in which she called on the delegates to commit to “not words, but action” in defense of democracy, so that people could “walk the picket lines free and unafraid and know that they are working for their freedom and their liberty.” (Read a longer excerpt of her speech below.)

EXTINGUISHED TOO SOON

Unfortunately, in the years after 1947, the CIO instead joined with corporations, the government, and the American Federation of Labor in an attempt to extinguish that spirit of militancy and unity.

Smith’s local was one of many that fell victim to that wave of attacks. Both CIO and AFL unions attempted to raid Local 22 in 1950, resulting in Reynolds workers losing any kind of union representation.

In the midst of these attacks, Smith died of a stroke at age 34, still fighting for her union. Later that year, the CIO expelled the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural, and Allied Workers (along with the Marine Cooks and Stewards) on charges of “communist domination”—the same charge it had leveled against my union, the UE, the year before.

Historian Robert Rodgers Korstad tells the story of Local 22 in his 2003 book Civil Rights Unionism. He describes Smith and her co-workers in Local 22 as being “on the front lines of efforts to advance the boundaries of democratic culture in the workplace, in civil society, and in personal relationships.”

As we celebrate Pride (and the anniversary of Local 22’s 1943 strike) this June, we can honor Moranda Smith’s legacy and too-short life by taking action to advance the boundaries of democratic culture—in our workplaces and unions, our communities, and our relationships with each other.

Jonathan Kissam is the communications director for the United Electrical Workers (UE). Love Songs from the Liberation Wars is a jazz opera about the Local 22 strike. To support efforts to bring it to Winston-Salem, or to bring it to your city or union hall, contact the Labor Heritage Federation.

‘Not Words, But Action’: Moranda Smith’s Remarks to the 1947 CIO Convention (excerpt)

I want to say to this convention, let us stop playing around. Each and every one of you here today represents thousands and thousands of the rank-and-file workers in the plants who today are looking for you to come back to them and give them something to look forward to: not words, but action.

We want to stop lynching in the South. We want people to walk the picket lines free and unafraid and know that they are working for their freedom and their liberty.

When you speak about this protection of democracy, it is more than just words. If you have got to go back to your home town and call a meeting of the rank-and-file workers and say, “This is what we adopted in the convention, now we want to put it into action.”

If you don’t know how to put it into action, ask the rank-and-file workers. Ask the people who are suffering, and together you will come out with a good program where civil rights will be something to be proud of.

When you say “protection of democracy” in your last convention, along with it you can say we have done this or that.

The people that lynch Negroes in the South, the people that burn crosses in the South, the people who put men in jail because they wanted 10 or 20 cents an hour wage increase will learn that the workers can walk as free men, because we have done something in action.