Longshore Young Workers Come to the Aid of Tenants Facing Eviction

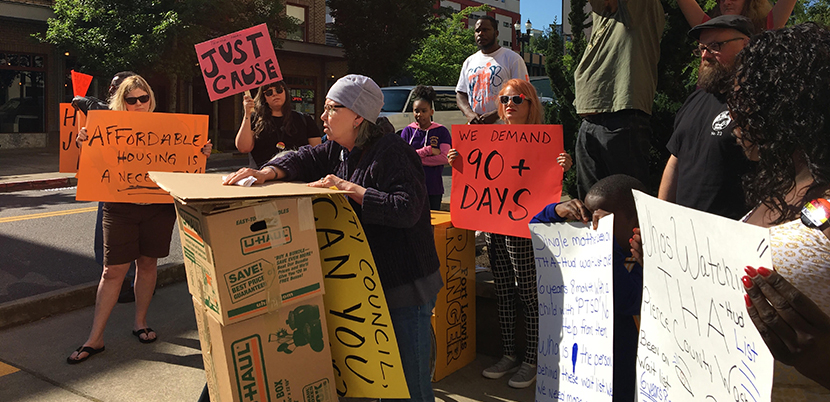

When a powerful developer came to Tacoma, Washington, and evicted an entire building of poor, disabled, and retired working people, members of the Longshore (ILWU) union local’s Young Workers Committee leapt into the struggle. Photo: Zack Pattin.

When a powerful developer came to Tacoma, Washington, and evicted an entire building of poor, disabled, and retired working people, members of our Longshore (ILWU) union local’s Young Workers Committee leapt into the struggle.

After all, the people at the Tiki Apartments were poor and working class. And what’s a landlord but another kind of boss?

It started in April 2018—right after we got back from the last Labor Notes Conference—when one of us went to an emergency meeting at the Tiki Apartments. The developer was going to kick everyone out of a 58-unit apartment complex, renovate the building, and double the rent. Here’s the kicker: what he was doing was legal.

We didn’t know a thing about tenants’ rights or disability justice, but we had learned a handful of skills in the union movement, like how to have organizing conversations, plan direct actions, and put pressure on employers.

This meeting, the first of its kind, was called by the Tenants Union of Washington. About 40 tenants sat in the courtyard, in a circle of mismatched chairs brought out from kitchens and living rooms.

JUST 20 DAYS

Folks started telling their stories. Some had lived there for 20 or 30 years. There was a retired teacher, recovering from a stroke, who struggled to use her hands and felt unprepared to pack or move. There was a retired Teamster who had just had back surgery.

A social worker was also a full-time student, suffering from chronic back problems. A woman who had recently finished trade school and joined the roofers’ union was struggling to overcome debts and rebuild her credit after a past eviction.

A blind woman in a wheelchair told us she was exhausted and scared, but not afraid to cry. She suffered from panic attacks and had already been on a three-year waitlist with the housing authority. Because building management had only taped notices to the doors, without knocking or making phone calls, for more than a week she hadn’t even known she was being evicted.

A single mother, fleeing an abusive relationship, had only been living here for a week. Management waited until she paid her rent—then notified her that she would have to move again.

The sale had been in the works almost a year. Management could have warned everyone months earlier. Instead it gave just 20 days’ notice, in a tight housing market.

The tenants were a cross-section of working-class voices: Union members. Dollar store workers. Women of color. Students. Formerly incarcerated people. Single moms. Single dads. Formerly homeless people. Recovering drug addicts. Retirees. People with disabilities.

Plenty of nonprofits sent representatives to the meeting: the veterans group, the housing authority, community services. But they just handed out pamphlets and cards that said, “Call this number, get on our waiting list, we have to process you before we can help you.” It was miserable. Their service model couldn’t respond to a crisis in real time.

KNOCKED ON DOORS

The group determined that the following Tuesday, we would take our tenant meeting to City Hall.

Over the next four days, a few of us from the Young Workers Committee, Tacoma Democratic Socialists of America, and the Tenants Union worked with the tenants to develop a strategy. We came up with a name, Tiki Tenants Organizing Committee, and a logo, and launched an aggressive social media campaign. We phoned every tenant who had attended the first meeting and asked them to knock on doors with us and talk to their neighbors. A few said yes.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

We paired tenants up with more experienced organizers. It was neighbors talking to neighbors. We already had a short list of demands that the Tenants Union had written up after the courtyard meeting. Two issues resonated with all the tenants: more time to find another place, and some financial help to get there.

We talked about the eviction notice—asking people what they needed and whether they had a plan for where to go. We also gave out flyers for the upcoming council meeting. We put in a rush order for 150 union-made buttons that said “Housing Justice Now.”

MOVE CREWS

Many tenants needed help moving—that’s what really brought our union into the fight. We made an appeal to guys we work with, many of whom aren’t very active in the union, that longshore workers should come down and do what we do best: move stuff.

So that week, while teams of tenants and allies canvassed, we also had crews of volunteers helping people move.

We got great pictures of these longshore moving crews and put them all over social media. Word spread fast. More and more members of the union asked if they could help. So did people from other unions—stagehands, electricians, state workers, teachers.

These “move crews” helped the tenants get to know us; it built trust and solidarity. The people we helped move stayed the most involved. Even after they got a new place, they stuck around and kept fighting for others.

On April 24, dozens of tenants and supporters packed the council chambers and demanded to be added to the agenda. People testified for nearly three hours. The mayor called for the city to hold an emergency meeting two days later.

PUT THE BRAKES ON

We went back and canvassed the apartments again. This time we asked tenants to prioritize their demands; overwhelmingly they picked “time” and “money.”

When we returned to the council the next day, the mayor revealed that the city had negotiated directly with the developer—and had gotten him to temporarily hit the brakes on the eviction.

The mayor also introduced a temporary emergency citywide ordinance requiring evictions of this type to provide 90 days’ notice. The council also approved $10,000 for a caseworker and asked for a daily update on the status of each Tiki tenant until every one was rehoused. City staff was instructed to come up with a list of ideas of everything we could do to make sure this never happened again.

The development at Tiki Apartments eventually went forward; it’s called Highland Flats now. After continued pressure, a small handful of the Tiki tenants were offered apartments at the renovated building, subsidized by the Housing Authority.

Our goal was now clear: strengthen the language in the emergency ordinance and make it a permanent law. We began working with tenants all over the city, helping them speak directly to their council members or to the media. We hosted tenants’ rights workshops in churches. We tabled at street fairs and flyered grocery stores and transit centers. As we spread across the city, we changed our name to the Tacoma Tenants Organizing Committee.

PROTECTIONS WON

It is with great pride that we get to say that we passed citywide tenant protections. Here’s what we got:

- “Source of income,” in other words how you pay your rent, is now a protected class—landlords can’t discriminate against low-income tenants who depend on federal Section 8 subsidies, for instance.

- All rent increases—of any amount—now require 60 days’ notice.

- Any termination of tenancy based on demolition or renovation requires 120 days’ notice. Landlords are also required to split relocation costs with the city.

- It’s illegal for a landlord to retaliate against a tenant for asking for repairs or for filing a complaint about a code violation.

- The city has strong enforcement language for violations of these codes. In some scenarios landlords pay a fine of $500 per unit, per day.

- And the same way that workers have a legal right to organize, we affirmed that tenants have a right to organize without retaliation.

Zack Pattin and Brian Skiffington are members of ILWU Local 23. They presented a version of this story last fall at their union’s Young Worker Conference in Vancouver, Canada.