Tax Act: Massive Giveaway to the Rich

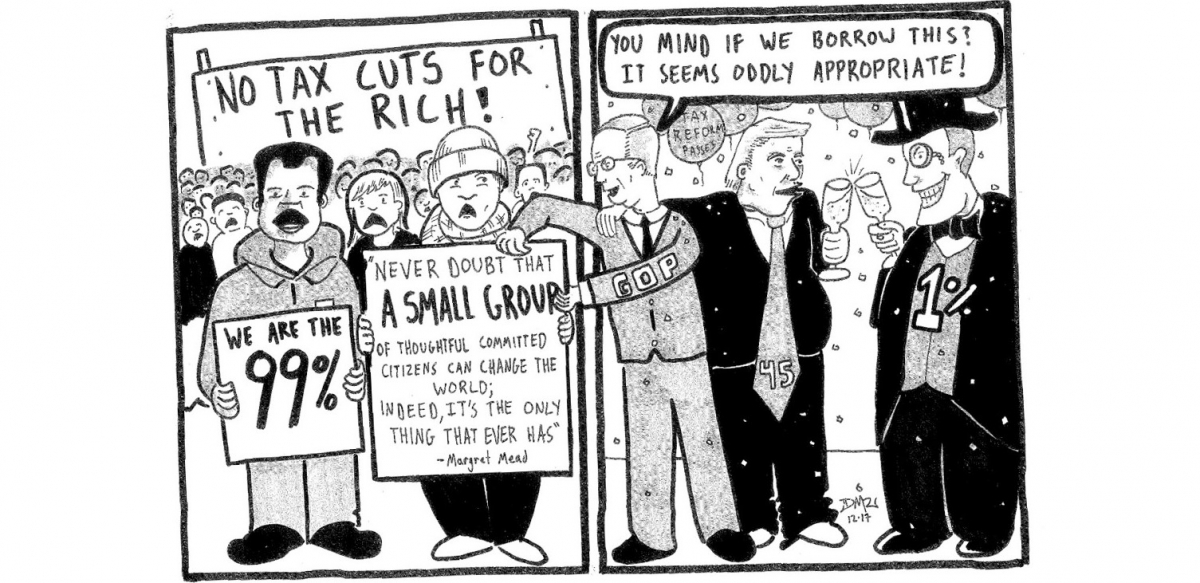

The tax act showers benefits on the best-off taxpayers. For the rest of us, it offers only meager tax reductions written in disappearing ink. Cartoon: Daniel Mendez Moore

Judging by what’s in the Tax Cut and Jobs Act, Donald Trump and the Republicans who pushed this disastrous bill through Congress in December must have thought American inequality wasn’t unequal enough.

Their act showers benefits on the best-off taxpayers. For the rest of us, it offers only meager tax reductions written in disappearing ink.

In 2018, the Tax Policy Center estimates, taxpayers with incomes of $1 million or more will get an average tax cut of $69,660, while those under $75,000 will get an average cut of $353.

By 2027, 81 percent of the tax cuts will go to those taking in more than $1 million, while taxes on those making less than $75,000 will go up.

BONANZA FOR THE 1%

First, the act lowers the top income tax rate from 39.6 percent to 37 percent, benefiting taxpayers whose income exceeds $426,700.

Second, it increases the exemption for the alternative minimum income tax, which benefits nearly exclusively taxpayers with over $200,000 of income.

Third, it doubles the exemption for the estate tax to $11.2 million. This overwhelmingly benefits the top 10 percent of income earners, and especially the richest 0.1 percent—those with annual incomes in excess of $3.9 million.

The act does put a $10,000 cap on the state and local taxes you can deduct from your federal income tax, a provision that will hit wealthier taxpayers in high-tax states. Residents of those high-tax states often vote Democratic.

Business owners and corporate stockholders will be especially rewarded. The act slashes taxes on corporate profits from 35 percent to 21 percent. Most studies find that more than three-quarters of the benefits of lower corporate tax rates go to owners of capital, rather than their employees, and close to half of the benefits go to the richest 1 percent of taxpayers.

In the name of providing tax relief to small businesses, the act allows one-fifth of the first $315,000 of profits of pass-through businesses (which pay personal income taxes instead of corporate income taxes) to go untaxed.

Over 80 percent of the benefits of this provision will go to the top 5 percent of taxpayers, including the Trump family, which owns more than 500 pass-through businesses.

EFFECTS CANCEL OUT

Republicans were far stingier when it came to taxpayers with modest incomes.

They did double the standard deduction—used by most low- and middle-income taxpayers—to $12,000 for individuals and $24,000 for married couples.

But at the same time, the act eliminates the $4,500 exemption for each taxpayer and each dependent. For a family of three, these lost exemptions will cancel out the doubling of the standard deduction.

The act doubles the child tax credit to $2,000. A family with two children and $100,000 of income will get the full $2,000 credit per child.

But because the credit is only partially refundable, a family with two children and $24,000 of income will get a credit of just $1,400 per child, and families with lower incomes will receive even less—as little as $75 per child.

The bill ends the itemized deduction for an employee’s unreimbursed job expenses, including union dues.

On top of all that, the bill scraps the Affordable Care Act mandate for individuals to buy health insurance or pay a fine. As a result, a projected 13 million fewer people will have health insurance.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Premiums will rise, for non-group plans, by “about 10 percent in most years” in the next decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Even if some of these cuts do help lower- or middle-income people temporarily, they’re set to expire in 2025. Taxpayers with incomes under $75,000 will actually see their taxes increase by 2027.

EXPECT NO BOOM

Tax cut supporters insist that this lopsided pro-rich law will create an explosion of economic growth that will create jobs and enrich us all. It’s not happening.

Cutting taxes on the rich is not an engine of economic growth, as plenty of evidence shows. The U.S. economy has logged its fastest growth when taxes on the rich were high. During the 1960s, the only decade in which annual economic growth averaged 4 percent, the top income tax rate got as high as 91 percent and never lower than 70 percent.

Compare that to the past 15 years. With a top tax rate of 39.6 percent, the U.S. economy has grown more slowly than it did during any decade from 1950 to 2000.

Why does taxing the rich actually help the economy? Part of the reason is that tax revenues allow more robust government spending to support economic growth. Gross government investment in the 2010-2016 period averaged just 3.7 percent of gross domestic product; in the 1950s and 1960s, the figure was greater than 6 percent.

Cutting taxes on corporate profits is similarly unlikely to trickle down. After-tax corporate profits, when compared to gross domestic product, are already nearing record highs. And our tax code is so riddled with loopholes that, despite a higher rate on paper, in practice U.S. corporations already pay about the same proportion of their profits in taxes as do corporations in other large, high-income countries.

Corporations are unlikely to use their windfall to make the investments that will jump-start economic growth, create jobs, and raise wages. After all, if they’re not investing now, it’s not because of lack of funds. In 2016, according to Standard and Poor’s, U.S. firms were already holding in the country $800 billion in cash and liquid assets, which they were unwilling to invest in long-term projects.

BOGUS BONUSES

Then there’s the discounted tax rate promised to U.S.-based corporations if they bring home the $2.6 trillion in profits they have stockpiled overseas. This too is likely to fail.

In 2004, the Bush administration offered a special 5.25 percent tax rate on repatriated profits. It managed to lure about $300 billion back to the U.S.—but corporations did not use those repatriated profits to increase domestic investment, jobs, or research and development.

Instead, a National Bureau of Economic Research study found that “a $1 increase in repatriations was associated with an increase of almost $1 in payouts to shareholders.”

Seemingly intoxicated by their coming tax windfall, some corporations are handing out bonuses to their workers. With its bid to merge with Time Warner blocked by the Justice Department, AT&T sought to make itself look good by announcing a one-time $1,000 bonus to more than 200,000 employees.

Walmart followed suit—but cleverly buried the fact that only workers who have been with the company for 20 years will get the full $1,000. The average Walmart worker is expected to get under $200. The bonuses will cost Walmart only 2.2 percent of the $18 billion it’s likely to save over the next decade from the tax cut, leaving plenty to hand over to shareholders.

Hours later, Walmart revealed it was closing more than 60 of its Sam’s Club stores and laying off thousands of workers.

WATCH OUT, SOCIAL SECURITY

On top of all that, this tax giveaway to the rich adds a whopping $1.8 trillion to the federal budget deficit, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Republican lawmakers are already bemoaning the ballooning deficit they’ve created and saying they’ll have to cut Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and public services to close the budget gap.

That’s a one-two punch that we need to make sure doesn’t connect.

John Miller is a professor of economics at Wheaton College in Massachusetts. He writes a regular column for Dollars & Sense magazine and with Arthur MacEwan is coauthor of Economic Collapse, Economic Change: Getting to the Roots of the Crisis (2011).

![Eight people hold printed signs, many in the yellow/purple SEIU style: "AB 715 = genocide censorship." "Fight back my ass!" "Opposed AB 715: CFA, CFT, ACLU, CTA, CNA... [but not] SEIU." "SEIU CA: Selective + politically safe. Fight back!" "You can't be neutral on a moving train." "When we fight we win! When we're neutral we lose!" Big white signs with black & red letters: "AB 715 censors education on Palestine." "What's next? Censoring education on: Slavery, Queer/Ethnic Studies, Japanese Internment?"](https://labornotes.org/sites/default/files/styles/related_crop/public/main/blogposts/image%20%2818%29.png?itok=rd_RfGjf)