Labor Lessons from Mississippi Freedom Summer

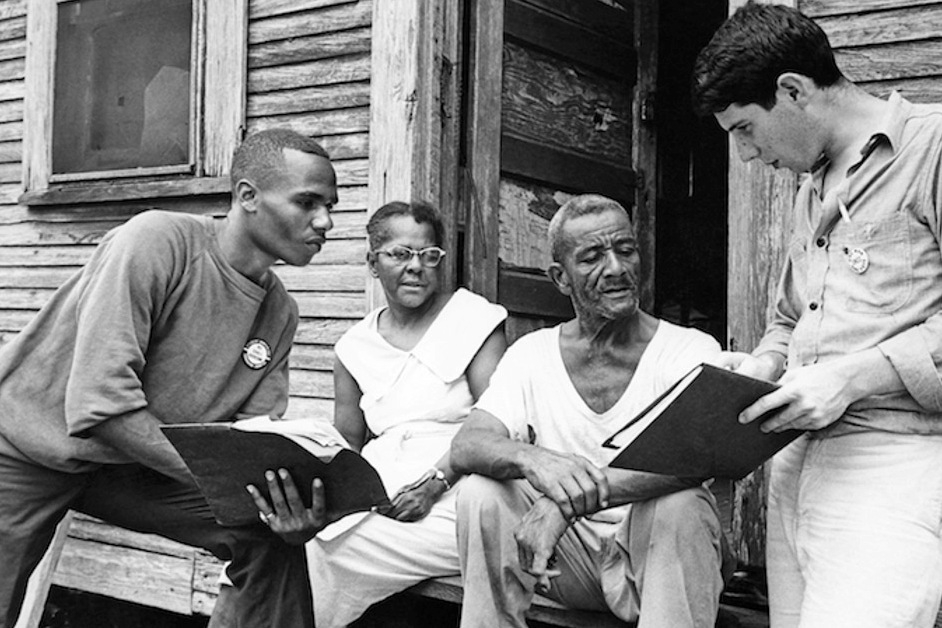

It’s the 50th anniversary of Mississippi Freedom Summer: the 1964 campaign, led by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, to register large numbers of African Americans to vote.

Not only hundreds of Black and white college students and other out-of-state volunteers but also thousands of Mississippians bravely joined the effort. Many endured arrests, beatings, bombings. Some were murdered. But in the process they embarrassed the U.S. on the world stage and moved the country to end Jim Crow.

While that summer’s campaign focused on political rights, the organizing holds plenty of lessons for unionists. Some, like Larry Rubin, carried those lessons into the labor movement themselves.—eds.

I was resigned to being killed, so when the deputy sheriff yelled in the middle of the night for me to come out of the Freedom House and go with him, I went.

It was the winter of 1964 in Holly Springs, Mississippi. The summer volunteers had gone back North. Four civil rights organizers—Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, James Earl Chaney, and Wayne Yancey—had been killed that summer, and those of us still in place were convinced our time would come sooner or later.

The deputy sheriff drove me into the piney woods without saying a word, and pulled into a small clearing. He asked, “Are you helping organize a union at the brick factory?” And because I thought I was going to die anyway, I told the truth: “Yep.”

“You keep that up,” the deputy said, “my brother works there and needs a raise.”

He assured me that white workers would vote for the union, even though none had signed cards. (The Black workers had been active in the organizing campaign even though a church where they met had been burned down.)

The voting was held a few months later and, sure enough, most of the whites—who, for all I knew, were Klan members—voted for the union.

UNION AWAKENING

As far as I know, this was the only instance where factory union organizing was part of a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee project.

We got into it not through any plan or policy, but because Black workers at the Marshall County Brick and Tile Factory came to the Freedom House, where we lived and worked, and asked us to help them get a raise.

From the time it was founded in 1960 until mid-’64, SNCC work was mostly aimed at gaining for African Americans in the South equal citizenship rights, especially the right to vote. Except for organizing sharecroppers to vote in county elections that determined who would make decisions about farm subsidies, SNCC did not until later directly touch on the economic inequality that burdened most Black people in the South. The same was true of the Southern civil rights movement in general.

More on Freedom Summer

Freedom Summer participants set up community-run Freedom Schools, where Black children and adults studied reading, math, Black history, and politics. They also organized the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the state’s white-only Democratic Party for seating at that fall’s presidential nominating convention.

To learn more, check out the PBS documentary “Freedom Summer,” which you can watch for free here, or read Charles Payne’s excellent book, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle.

And even today, auto workers in Canton, Mississippi, know their insecure jobs are a legacy of Jim Crow. To mark the anniversary, civil rights veterans joined students and workers to march on the Nissan plant, calling for a fair union election and declaring, “Labor rights are civil rights.”

But in the winter of 1964, in Mississippi, in a world divided strictly by race, during the months when groups of whites had stepped up the terror tactics that had always been used to enforce segregation—white and Black workers voted together for a union.

No white worker took a stand against segregation in principle—but they voted with Black workers. It was then I decided I would spend my life in the union movement.

WORKING TOGETHER

Even though in the end the company simply refused to recognize the union and nothing could be done, I learned a lot about organizing from the brick factory campaign.

I learned, for example, that as an organizer you might not be able to change racist attitudes among workers, but you can change racist practices.

Later, in a campaign in an Indiana plant, there was a staunch racist who many of the white workers looked to for leadership. It took a while, but I finally convinced him and his buddies that, like it or not, without the Black workers they simply did not have enough votes to unionize their plant.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

After that, they began to come to meetings with Black workers and to work with them against management’s vicious tactics. As time went on, I saw that without talking about it, their racist attitudes seemed to mellow naturally.

Of course, management tried to pit whites and Blacks against each other, and came close to doing so. But the union had the same approach to organizing as did SNCC: organizers embedded themselves in the community. Some took jobs in the plant. And they settled in for a campaign that could have lasted for years.

TRUST TAKES TIME

Just like SNCC, the union knew it had to organize the whole community to organize the plant—the owners of the stores where the workers spent their pay, and the preachers, ministers, and priests who ran the churches where the workers worshipped.

Most important of all, we had to reach out to the workers’ spouses. For many months, we hung out at the bowling allies, bars, and other places that the workers and their families frequented. We got to know them as full, three-dimensional people, not just as members of a potential bargaining unit.

After a while, we made home visits. We worked quietly and stayed below the company’s radar. No cards were given out to sign until we had developed an organizing committee with effective leaders who could reach out to their fellow workers.

In the 1960s, it often took SNCC organizers years to build enough trust among local people to help them overcome years of oppression and brainwashing. They did this by becoming part of the whole community.

Working as an organizer in later years, I saw that union organizers who took the time to build trust among the whole community were able to help workers overcome fear of company retribution. And they were able to make it clear to everyone that by attacking the workers’ right to organize, the company was attacking the wellbeing of the entire community.

Larry Rubin was a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee on and off between 1961 and ’65, first in southwest Georgia and then in Mississippi.