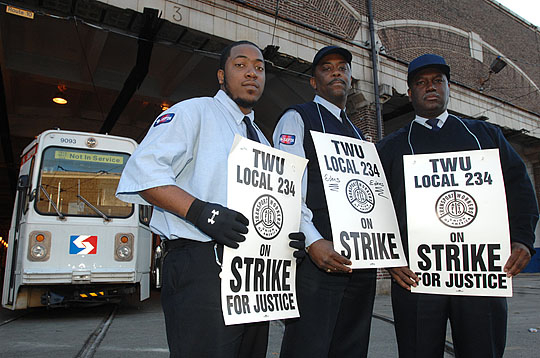

Media Howls as Philly Transit Workers Strike

Ending a dispute that underscored the need for stronger bonds between public workers and the communities they serve, Philadelphia’s transit workers went back to work in early November after a six-day strike.

The union—working without a contract since March—had demanded that Philadelphia’s transit authority, SEPTA, shore up an underfunded pension. Under the new contract, workers’ maximum pensions will be increased by $3,000 to $30,000 a year. Their contributions to the pension fund will be raised from 2 percent of salaries to 3 percent.

The five-year contract includes a first-year bonus in lieu of a raise, a 2.5 percent raise the second year, and a 3 percent raise each year thereafter.

Media coverage was marked by hostility to the strikers—and a scarcity of reliable information. When talks fell apart after a deal had been expected, the union was blamed for backing out. But the union had only agreed to “a handshake agreement on some of the big issues,” said Local 234 spokesman Jamie Horowitz, and was surprised when SEPTA delivered a proposal containing a number of separate provisions.

PENSION GAP OVERSHADOWED

Local 234 rejected SEPTA’s demand for a future reopener if the pending health care overhaul in Congress raises costs. The local also called for an audit of the workers’ chronically underfunded pension. SEPTA resisted the audit even though the union offered to pay for it. It appears that no audit was included in the final contract. But the union, considering a lawsuit, continues to push for an investigation.

Mike Zappone, who works at SEPTA’s 69th St. Terminal, says there is widespread concern among union members that their pension money has been misappropriated.

The pension has long been underfunded, with managers’ pension funded at a significantly higher rate. The workers’ pension is currently 53 percent funded, compared to managers’ 65 percent.

The TWU faced harsh attacks in the media. Several local columnists framed SEPTA workers as a labor aristocracy insensitive to the recession’s effect on other working-class Philadelphians. Reporting on the strike’s impact on riders far overshadowed any discussion of worker issues.

One particularly incendiary column blasted public workers for demanding better conditions while those of other workers were deteriorating. The union counters that members are running harder to stand still: raises, offset by increased contributions to the pension plan, probably won’t keep wages on pace with inflation.

A weekend demonstration called to protest the strike fizzled, however. One protester showed up, greatly outnumbered by an overeager press corps.

Negotiations between SEPTA and Local 234 have often led to conflict. “Every time we go for a contract it’s a battle. They always want to take something from us,” says Zappone, a 36-year SEPTA veteran.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Workers struck for seven days in 2005 over health care and for 40 days in 1998 over management attempts to convert positions to part-time and increase outsourcing. SEPTA workers have struck nine times since 1975.

This year’s walkout brought animosity between Mayor Michael Nutter and the union leadership to a boil. Nutter was kicked out of negotiations on the strike’s second day.

According to Horowitz, the mayor worried that a Local 234 victory would bolster the bargaining position of four other municipal unions that have been working without a contract since June 30.

The union, however, has been criticized for failing to reach out to those other unions—or to the public. No collaboration between workers and transit users took place before or during the strike—a crucial error during a stoppage that created widespread disruption, the local later admitted.

GOING IT ALONE

“It was a mistake to go out at 3 a.m. without giving public advance notice,” says Horowitz. “And frankly, we probably could have put a lot of pressure on the employer if we said, ‘hey, the clock’s ticking. The train won’t run if there’s not movement on these issues.’”

Zappone agreed. “We messed up the first day,” he said, allowing SEPTA to direct public anger against the union.

Local 234 missed an opportunity to connect its struggle over pensions to that of other workers facing a similarly precarious retirement, said Dorian Lam, a Philadelphia union organizer.

And Thomas Paine Cronin, a labor educator and retired president of AFSCME Council 47 in Philadelphia, said the bargaining positions of all the municipal unions were undermined by a failure to cooperate. Although the unions joined forces for a successful June rally before their contracts expired, momentum petered out.

Local 234 tried to recover its footing. At a press conference on the strike’s second day, President Willie Brown reframed it in terms of broader worker issues, emphasizing that the union was forced out.

Despite the missteps, Cronin says the TWU strike set a good example. “Rather than cave in,” he said, “they stood their ground.”