Government, Industry Play the Numbers Game on Worker Safety in Meatpacking Plants

In one of the most dangerous industries in America, injury rates were cut in half in one year. Is this possible? Only if you bear in mind the saying that “figures can lie and liars can figure.”

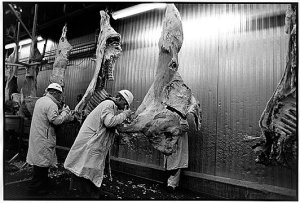

Meatpacking has always been risky for workers’ hands, arms, legs, and backs. A 1943 government study found that killing-floor workers averaged more than two dozen injuries each year and that meatpacking was America’s most dangerous industry.

But today the figures make beef and pork processing look far safer than it is. In the 1990s companies began keeping injured workers on the job, which reduced their reported injury rates and their worker’s compensation claims.

They were aided in 2002 by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which changed its recording methods so that the most common injuries in meatpacking are now exiled from official statistics. The result is that today’s government data seriously under-report injury levels in the meatpacking industry.

PUSH-BACK ON INJURIES

For a few decades after the 1930s, when the Midwest’s meatpacking plants were organized, unionization made a difference. Less than 10 years after the United Packinghouse Workers secured national contracts, meatpacking’s injury rate had plummeted.

As new firms such as IBP took over the industry in the 1980s and union strength declined, working conditions worsened. National union contracts disappeared and pay fell 30 percent. The injury rate increased 40 percent, with occupational illness—primarily carpal tunnel syndrome—growing an astonishing 442 percent between 1981 and 1991.

With little bargaining leverage over pay levels, union activists turned to activity around safety issues to retain a foothold in the industry. The immigrant workers who were entering the plants in droves often were unfamiliar with meatpacking and were outraged at the high level of disabling injuries.

In some cases spontaneous walkouts erupted, such as one at a Delaware poultry plant when an immigrant worker lost several fingers.

Public pressure also mounted on the industry. In the late 1980s IBP suffered a public relations disaster. A congressional investigation showed the company had systematically underreported injuries at its Dakota City, Nebraska plant by maintaining two separate injury logs.

The version provided to OSHA contained less than 10 percent of the injuries recorded by the company’s own medical staff. The investigation resulted in a $2.59 million fine against IBP for what one official said was “the worst example of underreporting injuries and illnesses ever encountered by OSHA.”

For their part, insurance firms that had to pay worker’s compensation claims raised their rates for the industry and made it known that they were not pleased with the high level of claims even with the inadequate compensation provided to injured workers.

RATES DROP BY HALF

These pressures had an impact. The high-water mark of injury rates was in 1991; over the next 10 years aggregate reported injury levels dropped by 50 percent. Some improvements came through ergonomic workstations and new safety equipment.

As important as any real improvements, however, was the employers’ decision to keep injured workers on the job—which lessened worker’s comp claims. Until 1981, injuries causing days away from work typically accounted for 45 percent of all injuries and illnesses. But by 2001 injuries causing absence from work fell to just under 10 percent—a great savings for the insurance industry.

Even with these improvements, meatpacking retained its undesirable position as America’s most dangerous industry. In 2001 meatpacking’s repetitive motion disorder “incidence rate” was 30 times higher than the average for all private industries.

CAN’T BEAT IT? REWRITE IT

So with a stroke of the keyboard, the BLS in 2002 put out a new set of rules for recording injuries:

1. Any restriction on the tasks a worker could perform that was limited to just the day of the injury was now not reportable. Thus a category used before 2002—injuries that resulted in “no lost days”—disappeared from the data, to be replaced simply by “other.”

2. The definition of “restricted work activity” changed. Under the old rules, “restricted work duties” took place when the worker could not perform any job duties typically expected throughout a calendar year. The new definition substituted “routine job functions” for “any job duties” and shortened the period considered to one week.

Say a worker’s job was processing meat, and after an injury she was moved to another processing job with different duties (such as moving meat by hand rather than cutting it). This would have been called “restricted work activity” under the old rules, but not post-2002.

Hey, she’s still working, isn’t she?

3. The new guidelines made it easier for firms not to report injuries resulting from ongoing activity (such as carpal tunnel syndrome) by changing the definition of reportable incidents. OSHA’s own summary of this change explained, “Aggravation of a case where signs or symptoms have not resolved is a continuation of the original case.”

This reversed the old rule whereby any injury was reportable, even if it was aggravation of an earlier condition, such as tendonitis. As a result, tables recording “repeated trauma disorders” simply disappear from BLS statistics after 2001.

HIDDEN INFO

So the aggregate data naturally look better than they used to. A year after the 2002 rules went into effect, injury rates magically dropped 50 percent.

Also telling is the fact that the supposed decline in injury rates did not continue: rates for both illness and injury have remained largely at their 2003 levels.

The irony is that even with the record-keeping changes, in 2006 meatpacking still had the highest injury rate among industries with more than 100,000 workers. Workers suffered occupational illness—which doubtless includes huge amounts of carpal tunnel syndrome under the “other” label—at a level 20 times higher than the average for private industry.

The result of the numbers game is that one-third of injuries and two-thirds of illnesses in meatpacking are classified simply as “other.” This has made it difficult or impossible to track and understand the nature of workplace dangers in the 21st century meatpacking industry.

Unions are relying, instead, on the blood-curdling stories their members still tell of the horrors inside today’s meatpacking plants.

An investigation of working conditions in meatpacking based on interviews with workers has not taken place since 1943. It is time to stop concealing the gruesome nature of this industry and give meatpacking workers the chance to detail the dangers they face every day.

Roger Horowitz is a historian with several books on labor and business in the meatpacking industry. He can be contacted at rh at udel.edu.