Baseball Players Defeated Non-Competes to Build Union

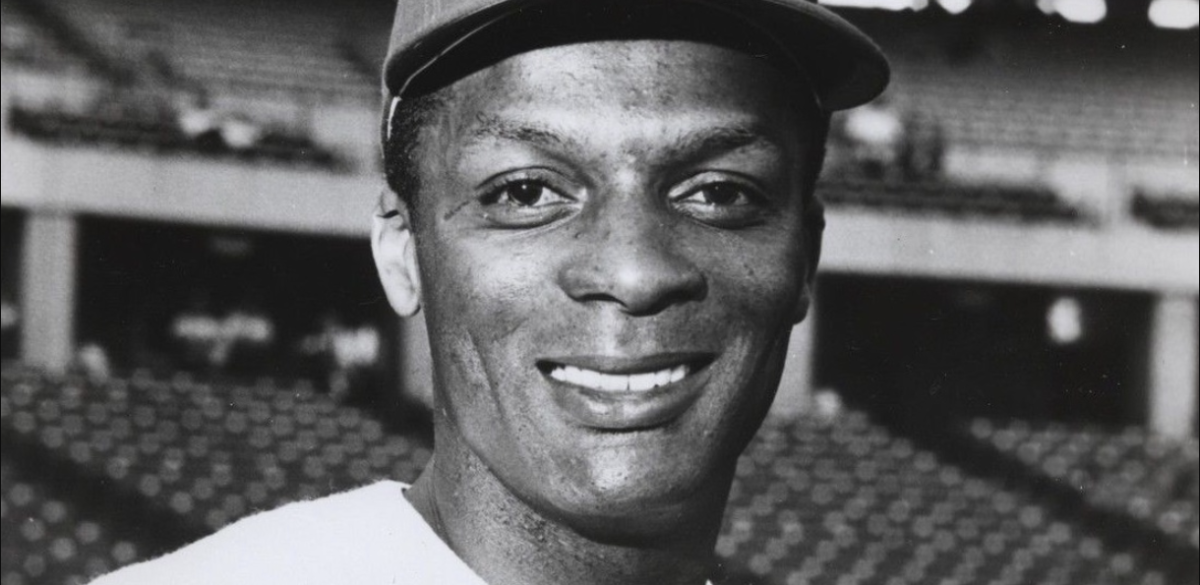

St. Louis Cardinals center fielder Curt Flood's resistance to the reserve clause paved the way for union victories in baseball. Photo: Wikipedia.

Banning non-compete clauses is a complement to, not a substitute for, union power. Just ask trailblazing baseball star Curt Flood.

The Federal Trade Commission has proposed to ban the non-compete clause—a type of coercive labor contract that prevents workers from leaving their employer to work for a competitor.

One in five workers labors under a non-compete agreement, costing workers $300 billion annually. The AFL-CIO was part of a large coalition of organizations petitioning the FTC for a ban on non-competes in 2019. Now the FTC is considering banning them.

The long struggle of Major League Baseball players shows how the fight against non-competes can be linked with increasing union strength.

BOUND FOR LIFE

In the 1960s, the average baseball player was not particularly rich. Pitcher Nolan Ryan noted in his Hall of Fame acceptance speech that he had to work at a gas station in the offseason to make ends meet before the players unionized.

In 1965, a group of players approached United Steelworkers economist Marvin Miller and asked him to serve as executive director of a newly formed players’ association. The players, not being seasoned trade unionists, wanted a professional negotiator to get them a good deal from the owners.

Instead they got an organizer. “You have to understand, we are adversaries,” he told the players. “If at any point the owners start singing my praises, there’s only one thing for you to do, and that’s fire me.”

A major cause of the low salaries and poor working conditions was baseball’s version of a non-compete, known as the “reserve clause.” Inserted into all player contracts, the reserve clause gave team owners the option to renew their contracts each year for one additional year.

The problem was, owners and the courts interpreted the clauses to extend into perpetuity. In effect, a player was bound to his team for life.

Owners, of course, had the right to trade players against their will. Because baseball enjoyed an exemption from the nation’s antitrust laws, owners were free to collude against players in this fashion. In other words, baseball players were treated as the property of their employers.

‘A UNION LEADER’S DREAM’

As baseball players at the time and Miller saw it, ending the reserve clause was a basic building block to building up the collective power of the union. Even unionized property was still property. As Miller and his organizing committee plotted out a strategy to build up the union’s power, along came Curt Flood, the star center fielder of the dominant St. Louis Cardinals.

The team was home to some of the most recognizable and outspoken Black stars in baseball, including Flood, Lou Brock, and Bob Gibson. The Cardinals beat the Yankees in the 1964 World Series and took away the Boston Red Sox’s “Impossible Dream” in the 1967 championship. (Perhaps not coincidentally, Boston was the very last team to integrate.)

Flood had long been among the most vocal athletes of the time in speaking out against racial injustice. He was raised in Oakland, and wrote eloquently in his autobiography about the shock and pain of playing under Jim Crow laws as a minor leaguer in the South, and being subjected to racist abuse around the country as an All-Star Major Leaguer.

At the end of the 1969 season, St. Louis traded Flood to Philadelphia. Flood refused to go—claiming that since his contract term was up, he was now a free agent who could play for the team of his choice. St. Louis claimed its rights to assign Flood wherever they chose under the reserve clause. A confrontation ensued.

Flood contacted the union. Miller warned him of the consequences—even if he won, he would likely never play again. Flood said he knew the consequences, but if it would benefit future players, he wanted to do it. Miller told him, “You’re a union leader’s dream.”

LOST AT THE SUPREME COURT…

Flood and the players association did not attack the reserve clause on the grounds that it distorted a blackboard model of perfect competition, as many economists do today. Rather, they emphasized that non-competes deprived players of their basic rights to autonomy and self-determination.

In a letter to baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn, Flood wrote: “I do not regard myself as a piece of property to be bought or sold.” Speaking to the press, he declared, “A well-paid slave is, nonetheless, a slave.”

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

With the backing of the union, Flood sued Major League Baseball to end the reserve clause. While former players Jackie Robinson and Hank Greenberg testified on Flood’s side, no active players dared challenge the owners.

In 1972, Flood lost his case at the Supreme Court in a 5-3 decision. The court ruled, absurdly, that baseball’s special status in American life entitled it to an antitrust exemption, which only an act of Congress could remove.

Nonetheless, Flood’s stand shone a bright light on baseball’s reliance on coerced labor and galvanized the other players into taking action. With the legal route exhausted, only one remaining vehicle could end the reserve clause—the contract.

…BUT WON IN ARBITRATION

In 1970, as Flood’s lawsuit was underway, the players’ union bargained for the right to have grievances heard by an impartial arbitrator. A cornerstone of virtually all union contracts, grievance arbitration seemed anodyne and bureaucratic to the owners, but in fact it represented the extension of democratic due process rights to the workplace—a major dent in an employer’s autocratic power.

The players then launched their first real strike in 1972, winning better employer contributions to their pension plan and proving their resolve. Their confidence grew.

At the end of the 1974 season, the arbitration clause would prove its value to the players—and come back to haunt the owners. In the offseason, pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally filed a grievance against their teams for attempting to renew their contracts under the reserve clause.

In 1975, arbitrator Peter Seitz ruled in favor of the players, deciding that the union’s collective bargaining agreement superseded the unilateral “rules” that the owners wrote to govern player transfers. Baseball’s non-compete was finally dead.

The owners fired Seitz in a fit of pique, and even postponed the start of the 1976 season. But the damage was done.

The union seized the opportunity that the end of non-compete clauses presented, using it as the cornerstone of what became an impressive apparatus of salary escalation. Miller and the players used the union contract to structure the labor market for players in a way that harnessed teams’ competition for talent to maximize salaries for all players.

Later union contracts—hard-won through multiple strikes—limited the supply of free agents in any year, causing owners to bid up salaries for the biggest stars, and then tied the salaries of the rest of the players to the resulting blockbuster contracts through salary arbitration. The result was an ingenious engineering of market forces that redounded to the players’ benefit.

Player salaries skyrocketed, as owners emptied their checkbooks to sign Reggie Jackson ($2.9 million) after the 1976 season and Goose Gossage ($3.6 million) after the 1977 season. And the Major League Baseball Players Association grew to become one of the most powerful unions in the U.S.

FREEDOM BOOSTS ORGANIZING

Today, since 93 percent of private sector workers lack the protections of a union contract, job-switching is one of the few means available for most workers to raise their wages.

During the tight labor market of 2019-2021, job-switching by low-wage workers increased their leverage over employers to such an extent that wage inequality actually decreased, as wage gains at the bottom exceeded those at the top.

These gains, since they’re dependent on a tight labor market rather than institutionalized in strong unions and collective bargaining agreements, are likely to be temporary. But workers’ increased confidence and bargaining power through job-switching also had another effect—almost certainly bolstering the organizing wins at Amazon and Starbucks.

To organize for power, workers need to be free. The FTC’s rule would increase their freedom. Just as Curt Flood’s fight against non-competes in baseball helped build his union’s collective power, so could a nationwide ban on non-competes help fuel the worker power and confidence necessary to rebuild the labor movement across the U.S.

Tell The FTC

If you have been harmed by a non-compete contract, tell the FTC about it. Even just a couple of sentences helps. Click here to submit a comment by March 20. The comment button is at the bottom of the page on the left.

Brian Callaci is chief economist at the Open Markets Institute and a member of the Nonprofit Professional Employees Union and National Writers Union.