New York City Municipal Employees Protest Abrupt Return to Offices

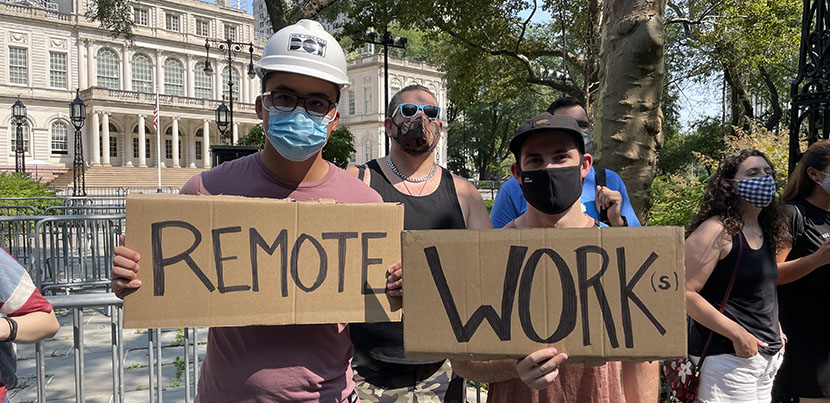

The day before the change took effect, 150 city workers rallied at City Hall in New York to protest a return-to-work order. Photo: Joe DeManuelle-Hall

Eighty thousand New York City municipal workers who had been largely working remotely for the past 18 months were forced back this week to full-time, in-person work—after less than two weeks’ notice.

The majority of the city’s 300,000 municipal workers were already back at work. Many—such as sanitation workers and health care workers—never stopped working in person. These remaining 80,000 were those the city had deemed “non-essential.”

Around the country, millions of office workers in both the public and private sectors have adapted to doing their jobs remotely. Many of those workers are now pushing to maintain some of that flexibility—particularly while the country is still in the throes of a pandemic. Some big employers, including tech giants like Facebook, have continued to extend back-to-office deadlines.

In New York, the week before the start date was peppered with town halls. Union locals and rank-and-file groups held online sessions to discuss the implications of the back-to-offices order and to plan how to respond.

JUST TWO WEEKS’ NOTICE

The day before the change took effect, 150 city workers rallied at City Hall to protest. The main complaint was “Is this really necessary?” from workers who had been working remotely, successfully, for months. Another concern was the apparent lack of planning by city officials.

“Many thousands of city workers will be forced back to work in spaces with poor ventilation,” said one city worker at the rally, “to do work that we can and have been doing effectively from home.” Workers complain of little to no ventilation in cramped spaces with no opportunity for social distancing. They also say that their administrators have done little - or nothing - to prepare.

Workers held signs reading “Remote Work(s)” and “I can do PowerPoint anywhere.”

The haphazard and accelerated push made it harder to organize resistance. Mayor Bill de Blasio made the proclamation less than two weeks before it was to go into effect. Many of the specific implications had still yet to be revealed by the time workers were showing up.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

The city’s largest public sector union, AFSCME District Council 37, attempted to negotiate with the mayor—which it had done over previous stages of reopening—and was rebuffed. The union is in the process of challenging the move legally and attempting to get an order to force the city to negotiate over conditions, though workers are already back in the office.

IT’S GOOD FOR REAL ESTATE

Pushing city workers back into offices has been a naked attempt to jumpstart the economy and the city’s prominent commercial real estate sector. Real estate developers and property owners are looking to the city to set the tone.

Since the city has the power as a large employer to force back tens of thousands of workers it can attempt to serve as a model for the broader mass of employers that haven’t brought workers back into their offices.

When the city first moved to bring back remote workers in May on a hybrid basis, de Blasio spoke about sending a “powerful message about this city moving forward.” A representative of New York’s powerful real estate lobby told The New York Times, “Above all else, this is a major momentum builder.”

‘CAN’T WE STRIKE?’

City worker activists hope that the visceral response from their co-workers can be harnessed for further organizing.

At the rally, Josh Barnett, an architect at the city’s Housing Authority and a chapter president in DC37’s Local 375, told the crowd: “For the first time in a long time, I hear co-workers saying, ‘Can’t we strike? Can’t we go on sickout?’

“I’m hearing people come up to me asking for the first time, not ‘What is the union going to do about this?’ but ‘What can we do about this?’ and ‘What are we going to do about this?’”