Open Bargaining Brings the Power of Members to the Table in Berkeley

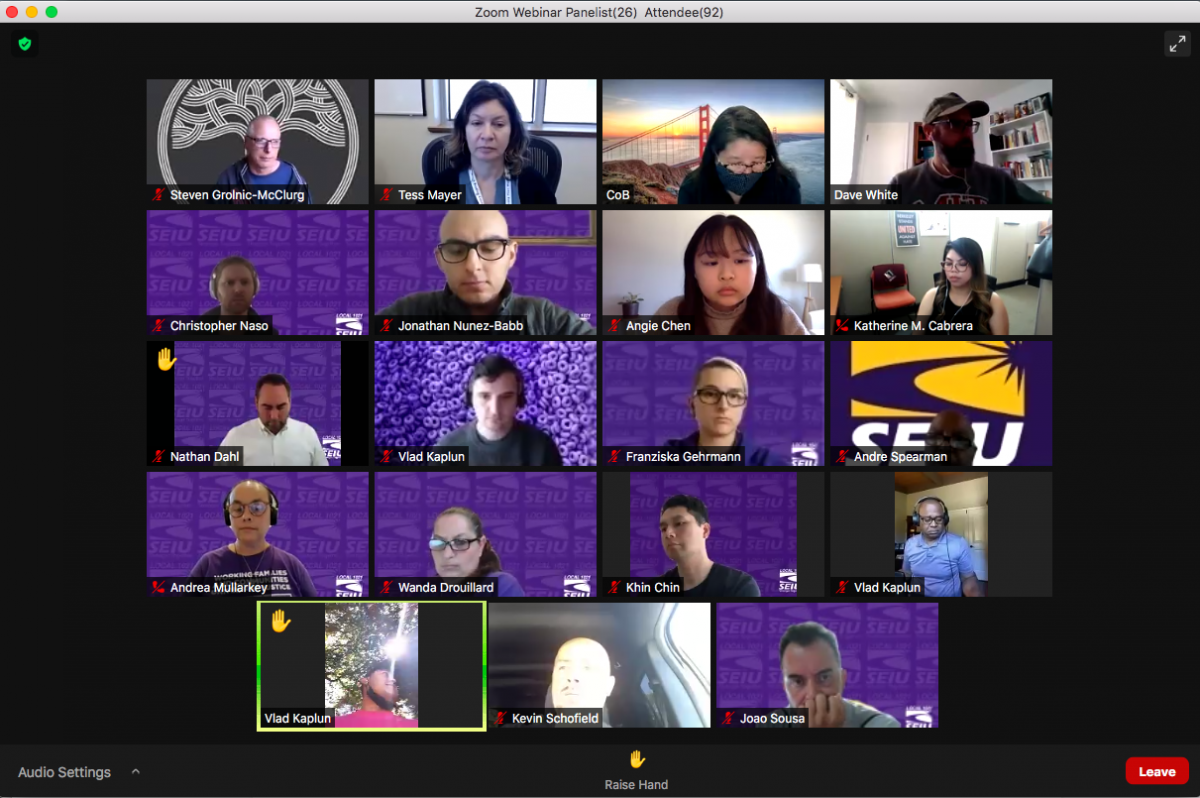

One SEIU Local 1021 chapter in Berkeley, California, held their ground on open bargaining, allowing over 100 members of the union and the public to observe negotiations. They won a better deal on pension equity and made gains for part-time employees. "The best part about open bargaining is the ability to agitate members more than we could ever do in lunchtime updates," said bargaining team member Angie Chen. Photo courtesy of author.

After years of salary scales that don’t keep up with the cost of living, an SEIU 1021 bargaining team for city of Berkeley workers decided to do something different at the bargaining table this year. They decided to go big—by opening up bargaining to all members.

This Local 1021 chapter—one of two at the city—includes librarians, recreation staff, homeless outreach workers, and fire department office employees. The chapter went into bargaining this year with some lingering distrust and division stemming from a 2013 state pension law that created a two-tier retirement system.

The change impacts public workers throughout California, though Berkeley’s implementation has resulted in an even more unequal situation than in most municipalities. New hires there take home hundreds of dollars less per paycheck than workers hired before 2013 owing to their pension payments. Frustrated members blame the union for the changes.

This time around, the bargaining team set out to win greater equity for newer workers and greater transparency in negotiations. “We decided to tell the members everything, so people can’t say ‘It was the union who agreed to it,’” said Franzi Gehrmann, a social services specialist who serves homeless residents. “Instead, everyone would feel that they had agreed or not agreed.”

“We felt that having a big transparent process would help the members feel involved, and could help hold us accountable,” said bargaining team member Andrea Mullarkey, a librarian, “so there’s no question whether each tier would back the other.”

At the same time they were in negotiations, the bargaining team was attending the Organizing for Power training, led by labor organizer Jane McAlevey, which helped convince them of the benefits of open bargaining.

CITY REFUSES TO SHOW

After some initial sessions where the chapter and the city agreed to ground rules and presented proposals, the bargaining team informed the outside negotiator hired by the city that it would be bringing a few extra people onto the next Zoom meeting. The ground rules did not forbid inviting members, nor did they specify which party would “host” the Zoom meetings.

The city’s contracted negotiator—who is being paid $665,000 to handle negotiations with seven of the city’s bargaining units, including the two represented by Local 1021—insisted that her team would not participate in an open process and would only speak to the bargaining team and union staff—no additional members allowed. When the bargaining team sent its own Zoom link for the next session, the negotiator simply refused to join.

“This happened for three weeks,” said Angie Chen, a member in the recently unionized legislative aides group. “So we didn’t bargain for three weeks. The negotiator would say, ‘We’re here on our link,’ and we’d reply, ‘We’re here on our link—with our members!’”

When the city refused to show up, the union team used the time to caucus with members who had come to observe on their lunch breaks.

RUSH THE ZOOM

After this three-week standoff, the team changed strategies. The union legal advisor had suggested the union should show good faith by joining the city’s video-conferencing link. So the team decided to rush the city’s Zoom room. “We brought 70 members and just rushed in,” said Chen.

But the negotiator again refused to bargain, leaving members even more offended, and triggering the Berkeley City Council to call an emergency meeting to decide the next steps. Members who had squeezed time out of their schedules to observe bargaining sent a barrage of emails to the City Council and made 30 public comments at the meeting, expressing their dismay that in supposedly progressive Berkeley they were being kept out of their own negotiations.

The public pressure worked. The city negotiator agreed to one public session—but stipulated that if chapter members could observe, the general public should be allowed to listen in as well.

No problem. Bargaining team members knew that their demands were directly tied to the needs of Berkeley residents—understaffing, for instance, has a palpable impact on public services. They felt that the people of Berkeley would side with them, so they welcomed opening the negotiations even further.

And at the initial public meeting, the union leveraged its dozens of witnesses to pressure the city into agreeing to more public bargaining dates.

IN THE SPOTLIGHT

Given the public nature of the sessions, the team worked especially hard to prepare, rehearsing for hours before the first one.

One person would be a spokesperson for each proposal or counter, and everyone else on the team would back that person up, taking turns pointing out how the city was being unfair to workers and harming the public in the process.

For example, when the city’s negotiator displayed a chart of city worker salaries in the region, one member pointed out how sad it was that public workers were paid so poorly. Another noted that the city’s salary proposal was still below inflation. A third called out the city’s continued refusal to agree to health benefits for part-time workers, referencing her fellow bargaining team member—a recreation worker with 15 years’ seniority who still had no health coverage nor even a city email address.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

“Traditionally in bargaining, the SEIU negotiator would do most of the talking,” said Chen. “We lifted up the people that each proposal would actually affect. We had members who were not on the bargaining team but were directly impacted by the proposal come and share their real story—like why they are considering leaving their job with the city.”

Again and again, bargaining team members connected the struggle of the workers with the needs of the public. At one public session, while 120 members of the chapter and the public listened in, Mullarkey called out the city’s habit of leaving positions vacant for extended periods in order to balance the budget. “The reality is, services are suffering,” she said. “If you want story time, you need a librarian to do it. If you want outreach to be done to encampments, you need someone to go to the encampment and do it... A vacancy reflects a reduction in service.”

CHALLENGES FROM WITHIN

Local 1021 also represents a separate chapter of city of Berkeley workers who were not interested in an open approach, which made collaboration challenging.

Union staff were also not supportive of the open bargaining process and had trouble adapting. When the union negotiator couldn’t convince the bargaining team to give up the open bargaining idea, successive layers of union leadership tried to talk them out of it.

Despite this, the bargaining team committed early on to go forward even without the backing of the staff. Union officials eventually accepted that this was how the member-leaders were going to run negotiations. “They just needed to be convinced,” Gehrmann said.

GOT THE GOODS?

After two months of public bargaining, the chapter and the city reached a tentative agreement, which was ratified by a 94 percent yes vote on July 26. Did open bargaining win the union a better deal?

The financial outcome of the new contract is about what may have been expected at the outset: a 7 percent increase over three years. But the chapter did win surprising gains that were especially important to members.

About one-third of the chapter’s members are part-time employees with no benefits, who have unusually precarious jobs for city workers. Recreation staff in particular experience last-minute unpaid cancellations for weather. These part-time workers gained some basic respect, like city email addresses and access to the same education benefits as the rest of the chapter, plus a one-time financial bonus and guaranteed pay if they are cancelled at the last minute.

The biggest division in the chapter—between members with the fully funded pension benefits and the members with the weakened and costly new version—was significantly lessened.

The city had already acknowledged the need to pick up more of the pension costs for newer members, though only over a six-year period (the timeline maintained in the other chapter’s contract). But this union chapter, by using public appeals during open bargaining and escalating public actions at city council and budget meetings, managed to bring the two tiers to equity in three years instead. This win will hopefully put pressure on the city to bring its other union employees into equity in three years as well.

PISSED=ACTIVATED

And the open bargaining process had its own benefits—separate from the outcome of the contract campaign.

“The best part about open bargaining is the ability to agitate members more than we could ever do in lunchtime updates,” said Chen. “When we say the city does not care if workers are treated equitably, that’s hard to convey when we say they didn’t meet us on COLA. But when we have members in the room while the negotiator is rejecting proposal after proposal even after our heartfelt presentation, it gets members angry. We’ve seen members really step up because they’re pissed.”

“It was a hard process, but I’m glad we did it,” said Gehrmann. “It’s helping the members learn that just wearing a purple T-shirt will not win us anything. The real gain is for the membership to get the understanding that if we want to win something you need to be there and be active.”

F. Thomson is a member of the SEIU Local 1021 Alameda Health System chapter in Oakland, California.