The Racist History of Right-to-Work

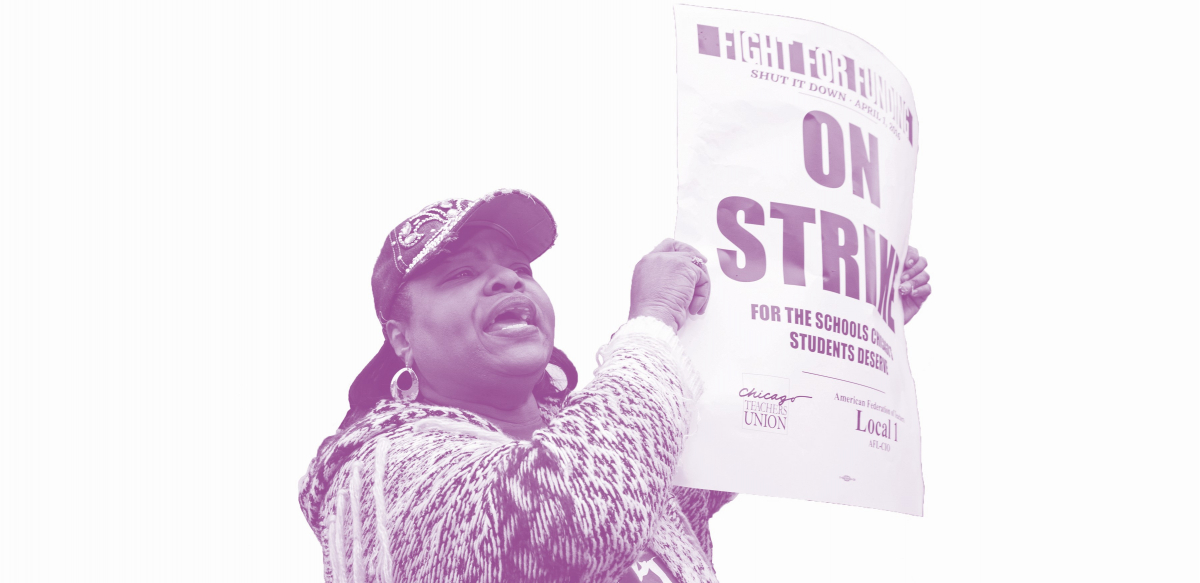

Credit: Jim West, jimwestphoto.com

“Right-to-work” laws originated in the 1940s as a strategy to maintain Jim Crow in the South.

The biggest pusher of the idea was Vance Muse—a well-heeled corporate lobbyist, white supremacist, anti-Semite, and professional anti-unionist from Texas who saw the New Deal as a Communist Jewish conspiracy.

According to Muse and his followers, the CIO was sending labor organizers to the rural South to inflame a contented but gullible African-American population and to force white workers to join unions together with Black workers and call them “brother.”

To stop this menace, his group teamed up with employers to push the first right-to-work laws, enacted in 1944 in Arkansas and Florida. (Californians voted no.) Many other states followed.

Rebuilding Power in Open-Shop America

A Labor Notes Guide

labornotes.org/openshop

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

“In our glorious fight for civil rights, we must guard against being fooled by false slogans such as ‘right to work,’” Martin Luther King, Jr. said in 1964. “It is a law to rob us of our civil rights and job rights.

“Its purpose is to destroy labor unions and the freedom of collective bargaining by which unions have improved wages and working conditions for everyone…Wherever these laws have been passed, wages are lower, job opportunities are fewer, and there are no civil rights.”

That’s still true. Union organizing has proven the most effective measure out there for lifting wages in general, and for reducing racial inequality. The upsurge of public sector unionism in the 1960s and ’70s was a particular boon to Black communities, since they were strongly represented in public employment—and Black workers led many of those union fights, often inspired by the civil rights movement.

Today workers of color remain strongly represented in the public sector, and the attacks on public sector unions still have a racist character.