All Tricks, No Treat in Peeps Candy Strike

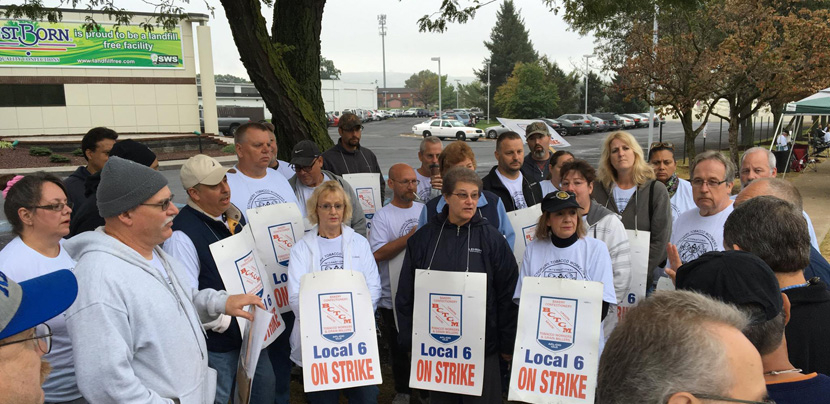

After three weeks on strike, the 400 workers who make Mike and Ikes, Hot Tamales, and that Easter basket staple, marshmallow Peeps, were driven back to work September 28—still without a contract. Photo: BCTGM

After three weeks on strike, the 400 workers who make Mike and Ikes, Hot Tamales, and that Easter basket staple, marshmallow Peeps, were driven back to work September 28—still without a contract.

Their employer, the privately held Just Born, forced them back through a combination of permanent replacements, younger workers crossing the line, and a looming cut-off of health care benefits.

Bakery Workers (BCTGM) Local 6 launched its strike just as the Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, plant was entering the height of “marshmallow season,” when Peeps production ramps up for major customers like Target and Walmart.

“We are typically running, at this point, six days a week around the clock,” said mechanic Keith Turner, chief shop steward on the third shift.

PENSION DRAIN

Just Born is pushing to eliminate pensions for new hires—a move that threatens the viability of the union’s multiemployer pension fund, which has 112,000 participants.

After the Teamsters’ Central States Pension Fund, the BCTGM’s is the second-largest pension fund with “critical and declining” status. It’s projected to run out of money in 14 years.

Under the Multiemployer Pension Reform Act of 2014, funds with this status can cut benefits—even for current retirees. Central States retirees have mounted a grassroots fight to resist the announced cuts to their benefits, and recently won a reprieve. But ultimately it will take Congressional action to get these troubled funds out of danger.

“The whole reason the pension fund is in critical status now is because of what Hostess did,” said John Price, the BCTGM’s director of organization. “They went to bankruptcy court and got out of $1 billion of withdrawal liabilities.”

The union is arguing that it’s illegal, under existing pension rules, for an employer to refuse to pay into the fund for all its employees. “You’re either all in or you’re all out,” said Price. To withdraw from the pension fund, Just Born would have to pay a $50 million fee.

“If they fail to pay pension credits on everyone, they put themselves into default,” said Turner, who has 21 years in the plant, “so someone like me would lose everything that we’ve put into the fund.”

The critical-and-declining status also requires employers to pay a yearly surcharge. Just Born wants workers to cover that through health plan premium increases.

LEFT OUT

Under U.S. labor law, employers may not fire workers for striking. But during an economic strike, they may hire permanent replacements—which amounts to almost the same thing.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

When the strike ends, those who have been permanently replaced cannot immediately return to their jobs. They’re placed on a recall list to wait for positions to open up, which can take years.

Fifty-six workers at the plant were permanently replaced. Among them was Jim Faulstick, a shop steward and fork-truck operator.

“You’ve got people who’ve been in there 38 years,” he said, “ready to get their Golden 80 so they can retire at a decent age, where they can live.” Some members become eligible to collect a full pension when their combined age and years of employment total 80.

“These are the very same people that made this company rich, made them their product,” Faulstick said. “It’s sad.”

The U.S. is the only industrialized country in the world where hiring permanent replacements is legal. “It’s one of the major threats in a union organizing campaign,” said Lance Compa of the Cornell School of Industrial and Labor Relations.

That’s why many unions position their strikes instead as unfair labor practice (ULP) strikes. If the strike was prompted by the employer’s violations of federal labor law—such as bad-faith bargaining or retaliation against workers for engaging in concerted activity—then all replacements are temporary, and strikers must be given their jobs back when the union offers to return to work.

A recent NLRB ruling may make it more difficult for employers to replace economic strikers. In the Piedmont Gardens case, the Board found that permanent hiring was unlawful because of an employer’s illegal motivation—to discourage future walkouts and punish workers for striking. (For more on that case, see Bob Schwartz's piece from the July 2016 issue of Labor Notes.)

CROSSED THE LINE

Seventy members crossed the picket line during the strike. Many were frightened by letters Just Born sent threatening to permanently replace strikers. The union has filed five ULP charges, including one alleging that the company had people call workers, posing as union reps and attorneys, to tell them how to cross.

If the employer commits ULPs, an economic strike can convert to a ULP strike.

Negotiations resumed October 18, with no movement from the company. As we go to press, 44 of the replaced workers are still walking the picket lines. (The others returned to the plant after new hires quit.)

“We’ve been getting overwhelming support from the community. They drop off food, drop off water, drop off money,” said Faulstick. “Our union brothers and sisters are doing a food drive for us. They took up a collection. They’re walking the line with us. I thank them every day I see ’em.”