Truck Workers Jump-Start Union and Reverse Two-Tier

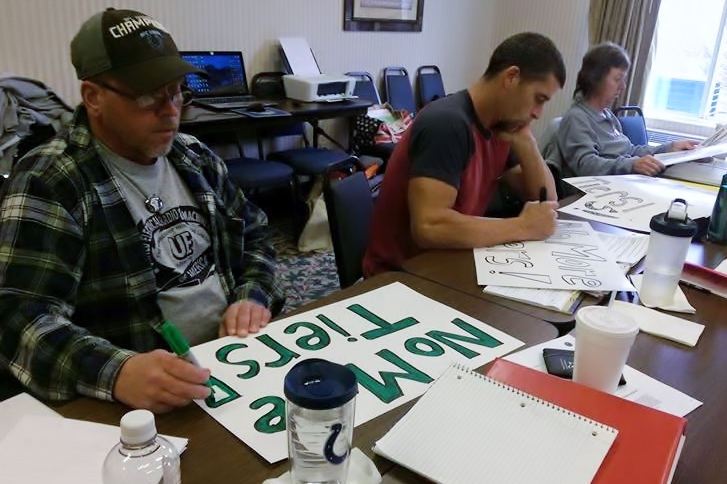

As part of their contract campaign, members parked in management spaces with signs opposing two-tier wages clearly visible. Photo: J Robert Burger

Factory workers who make heavy-truck suspensions in Kendallville, Indiana, approved a contract in March that will phase out their two-tier wage and pension system, bringing everyone within 40 cents of the top tier by 2020 and eliminating the bottom tier by 2026.

How’d they do it? With a vigorous contract campaign that showed the company, Hendrickson International, that the union’s 130 members were ready to strike. That’s also how they’ve maintained 99 percent union membership, despite Indiana’s “right-to-work” law.

United Electrical Workers (UE) Local 770 had accepted the two-tier wage and pension in 2010, after the company threatened to close the factory. Feeling the Great Recession’s pinch, the union acquiesced to a six-year contract, where new hires earned almost $3 an hour less for the same work.

Adding insult to injury, after the deal was ratified, the company laid off 10 workers and rehired them at the lower wage.

Hendrickson—which manufactures and distributes suspension systems for heavy-truck and bus manufacturers such as Peterbilt, Volvo, Mack, and Freightliner—soon made a full recovery from the economic downturn.

But on the shop floor, morale sank, and the union sputtered along for the next five years. “Our union wasn’t that strong,” said Derk Derck. “Sometimes we are lucky to even keep a president in office.”

In the lead-up to negotiations for the 2016 contract, Derck’s co-workers encouraged him to run for local president. He agreed on the condition that he have a strong executive board. He and other activists went around and asked the strongest union members to step up and join the leadership of the flagging local. They ran and won.

But to be strong enough to defeat two-tier, the new officers decided, they would have to rebuild their local from the bottom up.

STICKERS, SHIRTS, CAR SIGNS

TURN UP THE HEAT

How did Local 770 members build an escalating campaign to defeat two-tier? They started small and turned up the heat...

- Set a strike deadline

- Held their own shift meetings, on the clock

- Hauled burn barrels in their trucks

- Conspicuously circulated a strike petition

- Put signs in their cars and parked in management's spaces

- Showed up en masse to bargaining

- Held T-Shirt Tuesdays and sticker days

- Invited everyone to a bargaining workshop

- Surveyed members to develop demands

Learn to plan an escalating campaign with Secrets of a Successful Organizer. Buy the book and download free handouts like the Action Thermometer at labornotes.org/secrets

First, the new leaders formed a contract support committee of stewards and any interested members. They surveyed the entire union to develop demands.

Five top issues emerged and became the union’s primary goals: relaxing the attendance policy, increasing vacation days, reducing the penalty for retiring early, lowering health care premiums, and ending two-tier.

Next they needed to hash out a plan. Six months before negotiations would begin, three dozen members attended a bargaining workshop, open to anyone who was interested. (Leah Fried of UE International led the same workshop, “Build a Winning Contract Campaign,” at the 2016 Labor Notes Conference).

“We brainstormed in-house tactics to put the company on edge,” said Derck: “stickers, shirts, parking in management spaces, and showing up [en masse] for a bargaining session.”

Early on, committee members stressed personal conversations. Before talking with their co-workers, they met to practice listening to each other and making concrete asks. They started small, asking everyone to participate by wearing stickers that said “Hands Off Our Pensions” and “No More Tiers.”

Soon the union instituted “T-Shirt Tuesday.” Every Tuesday for months, the factory was full of workers wearing stickers and UE shirts to work. Members also made handmade signs for their car windows, calling for an end to two-tier.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Stewards watched to see who was participating in these activities. They kept talking with those who weren’t, trying to win them over. “Some people were scared at first,” Derck said, “but then they saw other people putting a banner in the back of their car, so they put one in theirs.

“Soon, people weren’t scared, and we organized a day where someone from every shift parked up front in management’s spaces, so they had to walk through the lot and see all the signs in the cars.”

NOT AFRAID TO STRIKE

The bargaining team, composed of equal numbers of first- and second-tier workers, invited members to attend a bargaining session. A few dozen workers came and sat quietly for hours, staring management down.

“You could tell they weren’t happy about it,” Derck said. “Just sitting in there for a couple of hours was enough to set management on edge.”

Members knew they had some leverage this time. Hendrickson had recently invested millions to build a new warehouse operation at the plant—making clear that it would be eager to keep production humming and avoid a strike.

Hendrickson had also received a city tax abatement of $11.3 million in return for its promise to expand the plant and bring 40 new jobs to the area. If the company were to shut the plant down or outsource jobs, it would be on the hook to pay the taxpayers back.

Stewards and committee members circulated a petition for a strike, knowing the company would see it. According to Derck, between 80 and 90 percent of the workforce signed.

The new officers had also instituted regular membership meetings, where workers brainstormed new tactics. One tactic that came out was for members to haul burn barrels to work every day in their truck beds, to show they were ready to strike.

Members started organizing their own shift meetings, while on the clock. Directly after the production meeting with management, instead of returning to their machines, workers would stay and listen as the steward shared bargaining updates and union news.

In the end, the bargaining committee won language on all five contract goals, including the phase-out of two-tier. The 10 workers who had been laid off and recalled at second-tier wages were immediately restored to the top wage.

“It’s not just what the bargaining committee did,” said Derck. “It was what we all did.”

STILL STRONG IN OPEN SHOP

This was Local 770’s first contract campaign since Indiana went “right to work” in 2012.

The union’s old contract had included a union security clause, where all represented workers have to pay their share in union dues. The right-to-work law bans unions from negotiating such clauses. In this new open-shop environment, workers could choose to opt out of the union and still benefit from the contract.

Derck was concerned that younger workers would drop their membership, feeling shortchanged by the two-tier system. And even some top-tier workers were growing skeptical of the value of paying dues, after the company started demanding cuts to their health care and pensions.

But through this contract campaign that dramatically increased participation and won big gains, Local 770 has maintained 99 percent membership.

“When we took these actions and won what we won, we learned how strong we are,” Derck said. “That is what is holding us together.”