Colorado Teachers and Parents Recall Hostile School Board Members

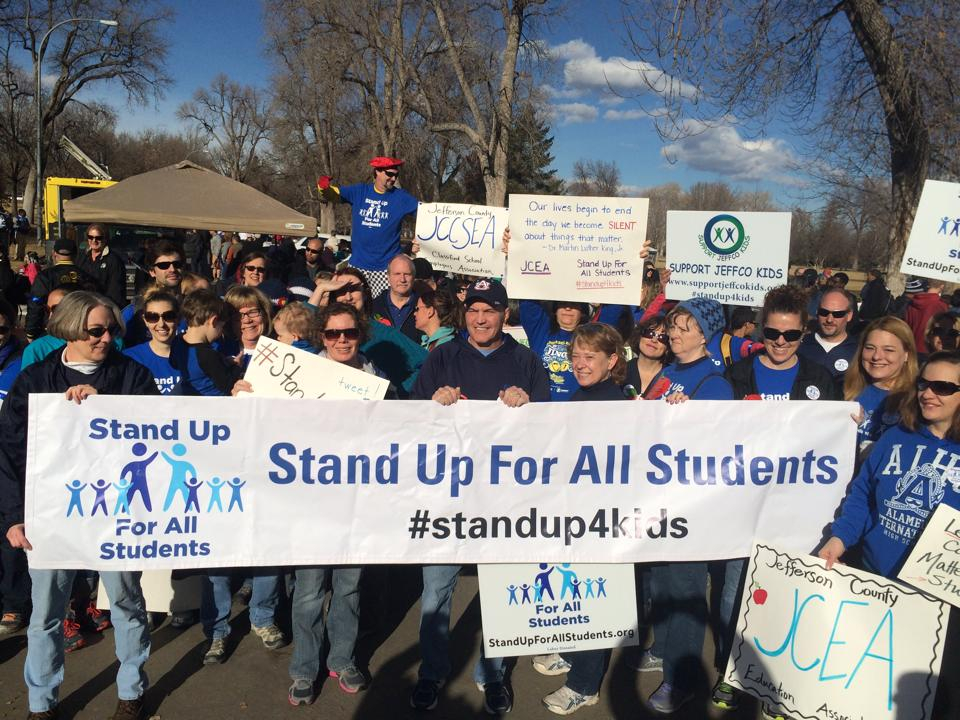

Teachers and parents in Jefferson County, Colorado successfully recalled three Tea Party-backed school board members. Photo: JCEA.

What issue could motivate one-third of union members to come out and knock on doors? For teachers in Colorado’s second-largest school district, Jefferson County, it was a fight for survival.

Last night, three Tea Party-backed school board members were ousted, with 64 percent voting to recall them.

They were the three who last year sparked district-wide protests and school walkouts against their plan to censor the U.S. history curriculum.

The election drew a national spotlight. The Koch brothers’ group Americans for Prosperity funded the incumbents’ campaigns.

So how did the recallers beat the corporate education reformers nearly 2-to-1? With shoe leather.

Jefferson County Education Association (JCEA) President John Ford reported that 1,200 teachers—out of a membership of 5,200—volunteered during the last six-week stretch.

“And that’s just the teachers,” he said.

Student and parent groups—formed during last year’s protests—were also key. The pro-recall coalition, Jeffco United, knocked on 100,000 doors.

Julie Williams, John Newkirk, and Ken Witt were first elected in 2013, part of a wave of conservative “reformers” taking over Colorado school boards. They formed a majority on the five-member Jefferson County School Board.

During their two years in office, Williams, Newkirk, and Witt imposed merit pay, diverted public-school funds to charter companies, and tried to make the curriculum more “patriotic.”

Their replacements were candidates supported by Jeffco United. Coalition-backed candidates also won the other two seats last night, creating an entirely new school board.

In neighboring Douglas County, three school board members backed by Americans for Prosperity were also defeated yesterday—although the seven-member board there still has a conservative majority.

Jefferson County teachers took notice when this majority was first elected in 2009. The Douglas County board implemented a school-voucher system that diverted public school funds to private schools. The board also refused to bargain with the teachers union, instead creating a merit-pay system and eliminating dues deduction. The Jefferson County board even hired Douglas County’s superintendent Daniel McMinimee, sending a message that anti-union tactics were spreading.

SICKOUTS AND WALKOUTS

Jefferson County is a sprawling suburban district west of Denver. It made national headlines in September 2014 when students and teachers protested the school board’s plan to review the curriculum for Advanced Placement U.S. history. The board wanted to make sure the history class promoted patriotism, free enterprise, and individual rights.

Weeks of protests followed, including teacher sickouts and student walkouts. High schoolers waved such signs as “Don’t make history a mystery” and “Protest is patriotic.” Parents expressed their outrage at school board meetings. The board eventually backed down.

Even before this controversy, the board had hired a costly lawyer to impose a fiscally conservative program; nixed funding for free full-day kindergarten, a program that especially benefited low-income parents and students; and increased charter-school funding by nearly 50 percent.

“They are trying to privatize public education through corporate charters,” Ford said. He pointed out that, while private and charter schools can cherry-pick which students to teach, “we take them all.”

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

The board also vetoed a previously settled deal with teachers, including a raise to make up for a pay freeze that teachers agreed to to help the district recover from the 2008 recession.

Instead the board imposed its own merit-pay system—based on an evaluation process that teachers say is flawed. Teachers are judged, in part, by their students’ standardized-test scores. Those ranked “highly effective” get a 1.3 percent raise, while those ranked “effective” receive less than a 1 percent boost.

Many find this system demoralizing.

“We lost 710 teachers in one year,” said Ford. “Our biggest concern is, if we go another year, there might not be anything left.”

STARTED WITH HOUSE VISITS

The seeds of what would become the recall campaign were sown even before the curriculum protests, in the summer of 2014, when JCEA leaders knocked on teachers’ doors to identify their concerns.

Next teachers hosted house meetings for their neighbors and friends to generate interest in fighting back against the board.

“People who attended the house parties said, ‘We have to get the word out,’” said Paula Reed, a Columbine High School teacher and JCEA board member.

The wave of house meetings and visits also helped the union sign up new members. While Colorado is not a right-to-work state, teachers in many districts, including Jefferson County, have the option to opt out of the union.

“We worked really hard to drive up membership,” Reed said. “People who swore up and down that they would never ever join, joined last year.”

A common reason for joining, she said, was: “When I look at the groups fighting for students, it’s the teachers’ unions.”

‘THEY COULDN’T STOP IT’

This past summer, teachers were in negotiations with the school district—and working with allies to build support for the recall.

They geared up for a possible strike, but opted for a 10-month contract extension in August so they could focus on the election effort.

Jeffco United activists knew their opponents were spending thousands of dollars on campaign ads, part of a statewide push for a conservative corporate model of education reform.

“It was intimidating, that’s for sure,” Reed said, “all the advertisements about how terrific school reform is. In the absence of any pushback, that could be pretty effective.”

But the coalition also knew its strength would come from going door to door to get out the vote.

“They couldn’t stop it when people talked to each other one-on-one,” Reed said. “You can’t stop that. You can’t buy that.”