Los Angeles Wants to 'Reconstitute' Pioneering High School Despite Major Gains

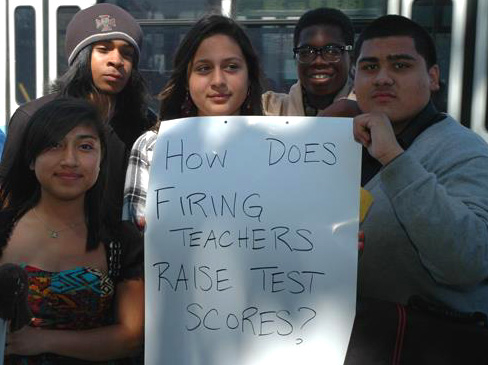

The Los Angeles school district plans to fire all the teachers from Crenshaw High and force them to reapply for their jobs, even though recent grassroots-led reforms at Crenshaw have won national praise. Students, parents, and others community members rallied with teachers when Manual Arts High faced a similar threat in 2012. Photo: United Teachers Los Angeles.

How should management respond when a group of union teachers pilots a nationally recognized reform model at a historically troubled school, working side by side with parents, students, community organizations, and academics, and makes big gains in the first year?

If you’re the Los Angeles school district, you fire all the teachers and start over.

The district has announced plans to “transform” Crenshaw High, one of only four majority-African-American schools in the district, into three new magnet schools for the 2013-14 school year. Magnet schools traditionally serve specialized student interests (such as medical magnet, arts magnet) and enrollment is usually based on application, though the district claims all students who would ordinarily be eligible to Crenshaw will be admitted.

More importantly, a magnet conversion allows the district to dismiss all the teachers and force them to reapply for their jobs. The conversion would disrupt the reforms that have been implemented at Crenshaw through its Small Learning Community structure.

When others schools in the district have undergone such conversions, more than half the teachers were not rehired. Dubious hiring decisions often exclude veteran teachers and outspoken union activists.

But students and community members, who helped create the school’s popular and successful new teaching model, are rallying with teachers to defend Crenshaw.

Grassroots Education Reform

Union teachers (members of United Teachers Los Angeles, UTLA), parents, community members, and academics collaborated to create Crenshaw’s Extended Learning Cultural Model and began to implement it last year under the leadership of the school’s then-interim principal, University of Southern California Professor Sylvia Rousseau.

A prestigious foundation grant allowed Crenshaw to pilot the model at two of the school’s small learning communities, which allow for magnet-type focus and personalization without requiring students to apply for admission.

The program linked classroom teaching relevant to the students’ experiences to work and internships in the community. For instance, students worked on food surveys at area stores to gauge the availability of healthy food, relative to the rest of Los Angeles. They also did community interviews to create a portrait of the America they live in, based on a book called Our America.

Teachers designed collaborative lessons across subjects. All students used the same set of school-wide data, looking at those data in different ways in each of their content classes.

The model was explicitly political, asking teachers to learn from and embrace their students’ cultures. One of Crenshaw’s goals is to create learners who are able to contribute to their neighborhoods.

Both parents and teachers did specialized work to support the model. The parents received “intentional civility” training as part of the plan, while the teachers received training and did research on how to teach students who are not academically fluent in English, are socioeconomically disadvantaged, or are students of color.

The program required teachers to spend hours of extra time each month learning, collaborating, and reflecting on their craft—but the results were impressive.

Wanting to Be in School

“There was an enormous jump in kids wanting to be in the classroom,” said Lewis King, a UCLA professor of clinical psychiatry, who helped lead the project.

The program’s success showed up on California’s statewide standardized tests, where Crenshaw met all but one of its goals in 2012.

Special education students made huge gains. African-American students scored higher than at six of the other seven high schools in South Los Angeles. On the high school exit exams, Crenshaw saw increased scores for all students in English and a 300 percent increase in math scores for students not fluent in English.

The turnaround is remarkable for a school that briefly lost its accreditation in 2005 and had struggled to make consistent progress on test scores ever since.

Punished for Success

But instead of praising Crenshaw’s teachers for these strides, the district informed them they would all be dismissed and invited to re-apply for their jobs.

In a letter to faculty, Superintendent John Deasy blamed four years of “less than adequate progress in the achievement of Crenshaw’s students.”

Deasy didn’t mention how the district played a role in creating those problems—subjecting Crenshaw to years of unstable leadership before Principal Rousseau arrived.

The school had endured 33 administrative changes since 2005, including five principals, when Crenshaw was stripped of its accreditation. When the Western Association of Schools and Colleges visited again in 2012, its report said that its Visiting Committee (VC) was “shocked and frustrated” at Crenshaw’s turnover.

The committee was impressed with Rousseau’s leadership, however, reporting that she had “captured the loyalty, support and respect of every student, teacher, staff member and parent that the VC met during the visit. The entire school is now working together as a team.”

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Special education teacher Christine Lewis agreed. “She was tireless,” Lewis said of Rousseau. “She met with us more than any other principal has met with teachers.”

Lewis looked forward to Rousseau’s continued guidance in the 2012-13 school year, as a coach or consultant to the school. This did not happen.

“It was as if she never existed,” Lewis said. “The extended learning model has disappeared.”

Angry

At a Crenshaw community meeting December 11, parents and students vented their anger at the district for abruptly halting the promising program after just one year and imposing “transformation” on the school—all without consulting teachers, parents, students, or community members.

“Magnets are not going to solve the whole problem,” said Crenshaw tenth-grader Tanness Walker. “The teachers here connect with their students. If they don’t get their jobs back, we’ll have to start all over with new teachers.”

Lewis agreed. “I have put a lot of my own time and money into making myself a better teacher,” she said. “I took out student loans so that I could get better content knowledge in math.

“My fear is that the teachers who will come in will only give the kids the minimum and not really expect much of these kids.”

Crenshaw graduate Irvin Alvarado said he was the product of his teachers’ belief.

“If it wasn’t for those teachers, I wouldn’t be in college today,” Alvarado said. “All that the teachers did, they did by the skin of their teeth. They did it with the barest of resources.”

Superintendent Deasy did not attend the meeting. District leaders stood impassively behind bookshelves as the new principal tried to explain to frustrated parents why their school was going to be radically altered.

King warned the magnet conversion would create “enormous distrust.”

“You cannot build on a sand bed,” he said. “You have to build on a rock. You have to build on the strength of the community, on what the community already knows.”

Resisting Top-Down Restructuring

The hopeful news is that the Crenshaw community is fighting back. Parent leaders are systematically organizing more parents into the movement. They’re holding house meetings, gathering petition signatures, and sending representatives to larger meetings with teachers, students, community members, black clergy, and more.

Students are organizing independently, through student government and the groups Taking Action and the Coalition for Educational Justice. Recent alumni are assisting the organizing efforts via social media.

A coalition of community organizations has held a series of town halls and helped parents and students focus their plan of action. And Crenshaw’s teachers and staff are backing them up by bringing union leaders and rank-and-file members into the battle—turning out supporters for meetings, writing articles on teacher email lists, and developing a plan to support Crenshaw in the coming year.

“All of our union brothers and sisters should stand behind us, because if they can do that at Crenshaw, they can do that anywhere,” Lewis said. “You cannot transform a school without the teachers.”

UTLA is pushing the district school board to formally support Crenshaw’s Extended Learning Cultural Model and to stop the restructuring.

The activists are also questioning the legality of Deasy’s restructuring by meeting with regulators.

Crenshaw has a strong ally in nearby Dorsey High, another majority-African- American school, which has been facing the threat of reconstitution itself for over a year. While the Dorsey community won’t know the district’s plans for their school until early in 2013, they’re standing side by side with Crenshaw and will fight together for true reform in public education—whether that fight is just for Crenshaw or for both schools.

When Deasy visited the school in November, Lewis said, he called the teacher organizing “very divisive.” That may have been wishful thinking on Deasy’s part. The truth is, the organizing is bringing people together—and that bodes well for Crenshaw’s future.

Joseph Zeccola is an English and drama teacher in the Los Angeles school district. He is also a member of UTLA’s board of directors and of PEAC: Progressive Educators for Action, a rank-and-file caucus within UTLA.