Rolling Strikes at CVS Halted as Company Gave In

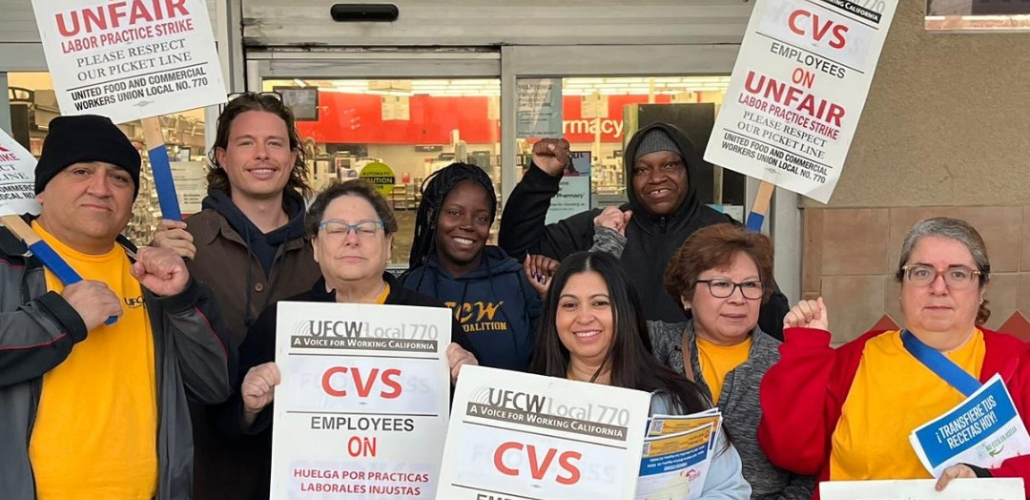

The union coalition had planned waves of strikes—but after the first wave, CVS came back to the table and reached a deal. “CVS underestimated its workers,” said Matt Bell, Secretary-Treasurer of Local 324. Photo: UFCW Local 770

This fall, workers at hundreds of CVS stores in California announced a rolling wave of strikes that seemed to take management by surprise.

Eight United Food and Commercial Workers locals bargaining together in California subsequently ratified a new contract in November with CVS, one of the largest health care retail conglomerates in the country. The units cover 7,000 workers, including pharmacists, pharmacy techs, store associates, and inventory staff.

The tentative agreement came shortly after seven stores in Los Angeles and Orange County struck for three days in October.

UFCW locals had been organizing for a series of unfair labor practice strikes in which stores across various locals and counties would walk out—but negotiations resumed days after the first batch of strikes.

“CVS underestimated its workers,” said Matt Bell, Secretary-Treasurer of Local 324. In his experience, companies usually start their psychological warfare well ahead of a strike: circulating misinformation and pleas to give managers another chance, and advertising that they’re hiring for open positions. Until the day before the strike, he said, CVS did none of that.

Pharmacy technician Kristona Carlton, a Local 770 bargaining committee member, estimated 90 to 95 percent participation in the strike at her south Los Angeles store, one of CVS’s busiest locations. She said the company struggled to find replacement pharmacy techs.

INSURANCE OUT OF REACH

The eight UFCW locals—5, 135, 324, 648, 770, 1167, 1428, and 1442—cover hundreds of CVS stores, about 60 percent of the stores in the region.

About a third of the unionized CVS stores in Southern California used to be branded Sav-On, a grocery and pharmacy chain that has largely been absorbed by Albertsons and CVS. The newer CVS stores have steadily organized, largely on the retail side—though some include the pharmacy staff as well, or the pharmacists organize into the unit later.

CVS has three arms: the retail stores and pharmacies, a pharmacy benefit manager which manages prescription drug benefits, and Aetna, the health insurance provider. The conglomerate raked in $8.3 billion in profit in 2023, twice what it made in 2022, though that growth has slowed a bit in 2024.

Even though they work for the company that owns Aetna, affordable insurance has been out of reach for the majority of retail workers at CVS. It was at the top of their demands for this contract, along with wages to keep up with inflation and enough full-time hiring to fully staff the stores. Those in former Sav-ons do have affordable insurance, and members hoped to close the gap.

So did they get there? Not all the way, though Local 324 bargaining team member Vincent Chairez says the new contract represents an impressive improvement. In lieu of cheaper insurance, workers who don’t have the Sav-On legacy contracts will get a payment into a health savings account.

Raises are more than $1 an hour this year, then 90 cents an hour next year and the year after that. The unions extracted a guarantee that CVS will hire more full-time staff, which locals will monitor through biannual staffing reports the employer will provide, and some other perks meant to retain staff, like longevity raises.

For members of UFCW Local 770, the three-day strike was transformative. Carlton says, regardless of individual members’ opinions on the contract, “They have the common goal that CVS should treat us better. They see that you can fight for what you deserve, that you don’t just have to stand and take things. Their voices were heard.”

PAINSTAKING PREPARATION

Months of preparation—and strike pay—helped with the strong strike participation rate. Grocery workers who participated in the UFCW Special Project Union Representative program, which pays them to work on various organizing campaigns (similar to other union “lost time” programs), played an important role in building up the CVS campaign.

Chairez, who describes himself as “the most annoying question-asker,” has been organizing his own store for the last couple of years and generating leads in non-union stores nearby. He even helped organize 20 new pharmacists into Local 324.

To get his co-workers ready to walk out, Chairez “made a detailed list of everyone at my store. I wanted to have a one-on-one without people nearby listening, to make sure people can ask questions like ‘How does a strike fund work? What is a rolling strike?’”

It’s not uncommon for a CVS store to have a non-union CVS down the street. In these cases, the union wasn’t able to shut down the striking stores entirely; managers could schedule workers from nearby non-union stores. Among union members, though, some stores had 100 percent strike participation, and others very high, according to Local 324.

In Southern California stores, the union has filed unfair labor practice charges against CVS, including for surveilling bargaining team members, threatening workers for wearing pro-union buttons, denying union reps access to worksites, and refusing important information necessary

for bargaining.

BIGGER BARGAINING

Meanwhile, 3,500 Rite Aid workers represented by an overlapping group of UFCW locals in California also voted to authorize a strike on October 18, although a strike never came to pass. They ratified their contract on November 24.

Between them, these workers represent all unionized CVS and all Rite Aid stores in California. Rite Aid is completely unionized in the state; one-third of CVS stores in the state remain non-union.

While the CVS and RiteAid workers have bargained together before, this is the first time either group has ever gone on strike. The two largest locals in the coalition, Locals 770 and 324, have been leading the organizing push. They represent a majority of the CVS workers, and are also the two largest locals overall, with 50,000 members mainly in grocery and retail throughout southern California.

Several of the same locals, including Locals 770 and 324, are also involved in coordinated bargaining with grocer Kroger, as part of a larger effort with other locals in the western U.S., including Local 3000 in Washington and Idaho and Local 7 in Colorado and Wyoming. Coordinated bargaining is a major demand of the reformers in the UFCW, whose memberships are fractured across many stores and whose contracts are fractured across locals.

NATIONAL RIPPLES

Building momentum for coordinated bargaining and reviving the strike are two key goals for supporters of Essential Workers for Democracy, which is organizing to revitalize the UFCW. EW4D held a Zoom call in September with striking grocery workers from UFCW and the independent New Seasons Labor Union in Portland; these strikers shared lessons with workers at CVS as they prepared for their own strike.

Nationally, only 4.6 percent of pharmacy workers are unionized. But a wave of worker activity has emerged in nonunion pharmacies since Covid. Last year workers walked out of non-union CVS and Walgreens stores in a series of strikes dubbed “pharmageddon.”

Some of the organizers of those walkouts, who included pharmacist social media influencers, went on to start The Pharmacy Guild, a new union affiliated with the health care division of the Machinists. Workers in eight units have since filed for elections with the Guild, which was supportive of the UFCW strike in California.