First Tire Workers to Organize in 40 Years Win First Contract

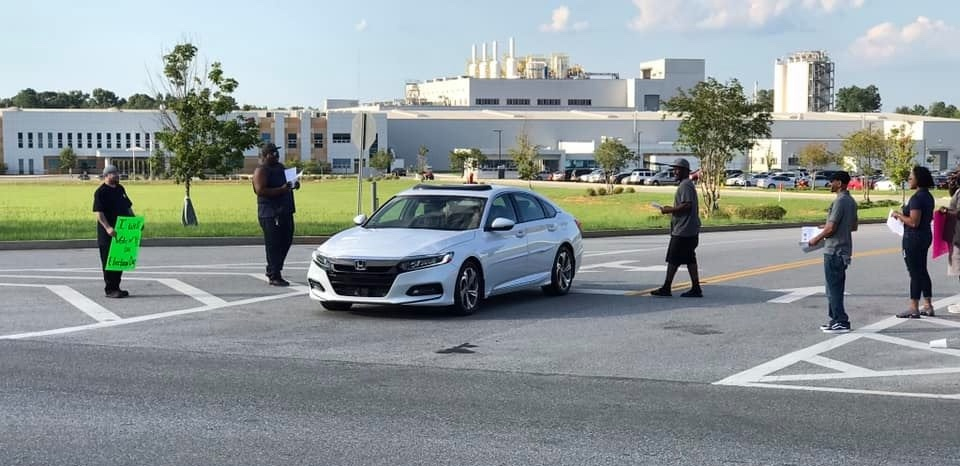

In 2020, workers at Kumho Tire in Macon, Georgia, became the first U.S. tire workers to form a new union in 40 years. In August, they won their first contract. Photo: IndustriALL

It was late summer 2017 at the Overtyme Bar and Grill, a hotspot off a busy highway in Macon, Georgia, and Kumho Tire plant worker Mario Smith had important questions for local United Steelworkers (USW) president Alex Perkins: he wanted to know how he could bring a union to the one-year-old factory.

Now six years later—after two elections, many National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) cases, a virulent union-busting campaign, and the triumphant solidarity of the factory workers—that union has gained its first-ever collective bargaining agreement with Kumho Tire management, the first tire workers to unionize in the United States in 40 years.

A CONTRACT VICTORY

Kumho Tire’s 300 employees will receive a 3.5 percent annual wage increase for the first three years of the four-year contract, ratified August 10. They won clear procedures for transferring between positions, and these positions now have grades, meant to keep a worker’s pay in line with the strenuousness of their job.

Any paid time off they use will count toward overtime pay. Workers will have paid lunches, which will cut the length of some employees’ shifts without reducing their pay.

In a workplace where employees were often at the mercy of their supervisors’ whims on matters of pay, employment, and discipline, workers will now have the protection of a grievance and arbitration process.

“It protects their livelihood,” said Perkins, now a USW staff representative. “Now these people can go to work and be comfortable with saying, ‘I’m going to purchase a house and purchase a car, because I know as long as I go to work and I do my job, I can’t just be terminated because the supervisor doesn't like me.’”

Workers also won a vital health and safety protection: if they deem a machine unsafe to operate and have notified a manager and a union rep, they’re not required to operate the equipment until the problem has been resolved.

“That really hit home for me,” said James Golden, a belt operator who once suffered a concussion on the job and had to have medical staples placed in his head.

The union also bargained for a joint improvement committee of three factory employees and three corporate employees. Golden, a member of the bargaining committee, said he realized during negotiations just how clueless management was about conditions in the plant.

“Our immediate supervisors put up this perfect picture for them, so the higher-ups were completely unaware of a lot of things that were going on in the plant,” Golden said. “Not saying you can’t trust your supervisors, but when your supervisors are showing you they’re untrustworthy, you can’t expect them to go to management and tell them your concerns, especially if your concern is something that might make them look bad.”

He believes the committee will provide a needed space for workers to speak frankly, “so we can actually sit down with someone who will listen and possibly change some things.”

LONG ROAD TO UNIONIZATION

Kumho Tire workers’ first union contract was more than two years in the making—and the fight for legal recognition of the union was even longer.

The struggle began just a week after Smith and Perkins talked at Overtyme Bar and Grill—Perkins gave Smith a stack of union cards to distribute to his co-workers.

Perkins was shocked at the high rate at which workers offered their support for the new union. USW filed a petition for a representation election with the NLRB on September 17, 2017, with more than 85 percent of the workforce signed up on cards.

A month later, workers lost the union election 136 to 164.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Of course they had not suddenly changed their minds about the benefits of union representation. But for enough of them, management had succeeded in undermining hope.

“Fear tactics, indoctrination—there was heavy pressure to say we don’t need a union,” Golden said. “You would not believe the extremes that they went to.”

The union-busting campaign included hours-long captive audience meetings and harassment to intimidate workers into voting no. Management created a sense of surveillance and fear, and threatened that the plant would close and everyone would lose their jobs if the union won. According to worker testimony to the NLRB, supervisors showed “help wanted” ads—saying that if the union won, everyone would be looking for a job—and claimed that workers would be forced to sign up for overtime work in a union facility.

After their election loss, pro-union workers filed unfair labor practice charges with the NLRB. In May 2019, an NLRB administrative law judge ruled that management’s union-busting campaign had been so severe that union supporters had the right to another election. The judge also ordered that management read a full list of its labor infractions to employees at a meeting that they were all required to attend.

(Now, after the August 25 NLRB decision in the Cemex case, if an employer commits an unfair labor practice so egregious that it would necessitate another election, the employer will automatically have to recognize the union instead, if the union filed for an election with majority support.)

It took until August 2020 before the NLRB had settled the contested ballots from this second election. Kumho workers won their union by a margin of just one vote.

STALLING TACTICS

Next came the battle for the first contract, and it was hard-fought. Management stalled at the bargaining table.

“They’ll be late for negotiations,” Golden said. “They’ll come in late, stay for an hour or so, go to lunch for two hours, come back for an hour or so, leave. I think their thing was stall, stall, stall, and they 100 percent made sure they did that.”

Golden said this refusal to bargain was a maneuver to damage union members’ morale. And indeed, the delays took a toll.

“I think with them stalling it, it killed the people’s belief in what we were doing,” Golden said. “It made it seem imaginary to the people, like they never thought we were actually going to get it done.”

“It was a lot of disbelief,” Perkins said. “Some people never envisioned being able to have a contract because it had taken so long. And it was a little bittersweet because we’ve had people that have been fighting to help to get a union at this location for so long, and a lot of them have left and are no longer employed there.”

Smith, who originally sparked the union drive, was fired just four days after the conclusion of the October 2017 representation vote, which he had organized. Smith filed a charge that his termination violated the NLRA, but the NLRB’s General Counsel did not go to a complaint on the charge. Smith now works at another USW-represented plant.

But for the workers who remain, union representation and a contract victory herald a new era at Kumho Tire.

“I know that one time I was thinking about leaving, but I'm glad I stuck it out,” said Melinda Jones, who works in the raw materials lab. “Because we're through with [union-busting]. We won.”

Finley Williams is a student at Cornell University and a Labor Notes writing fellow. For more on the Kumho workers' campaign, see the USW's video, "The Story of USW at Kumho Tire."