Viewpoint: What Message Does a ‘Vote No’ Campaign Send?

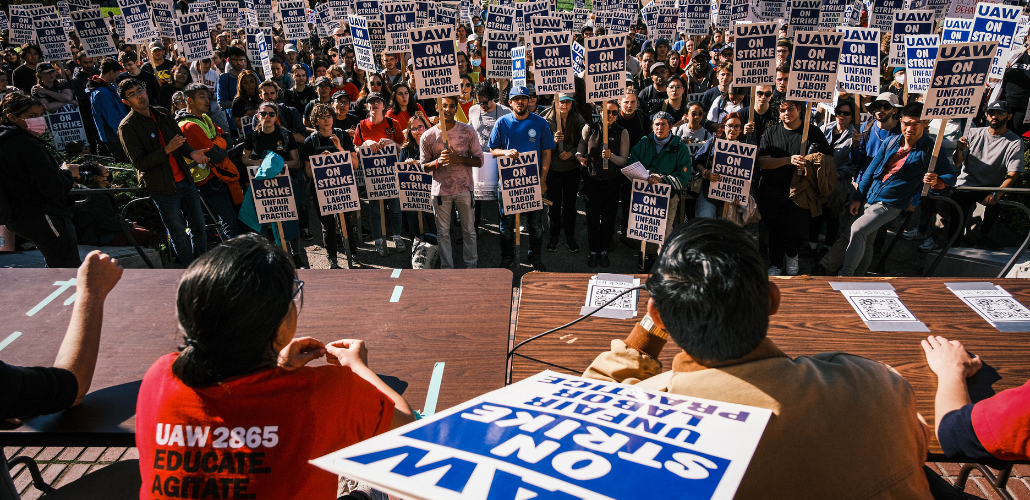

Academic workers at the University of California ended their strike last month. Nonetheless, activists reported that the vote no campaign had expanded the core of organized rank and filers. Far from sending a message to the boss that the union is divided and vulnerable, a vote no campaign can be viewed as a sign of strength. Photo: Ian Castro

In December, the contract bargaining team for Auto Workers (UAW) Local 2865 brought back a tentative agreement with the University of California and presented it to its membership of teaching assistants, graders and tutors for ratification. A lively “vote no” campaign arose.

A vote no campaign sends a very public message. Does it tell the boss that the union is divided, and therefore weak, or does it warn the boss that members are ready to fight for more? What does it say about the union and the union leadership?

THE MAIN ISSUE IS TRUST

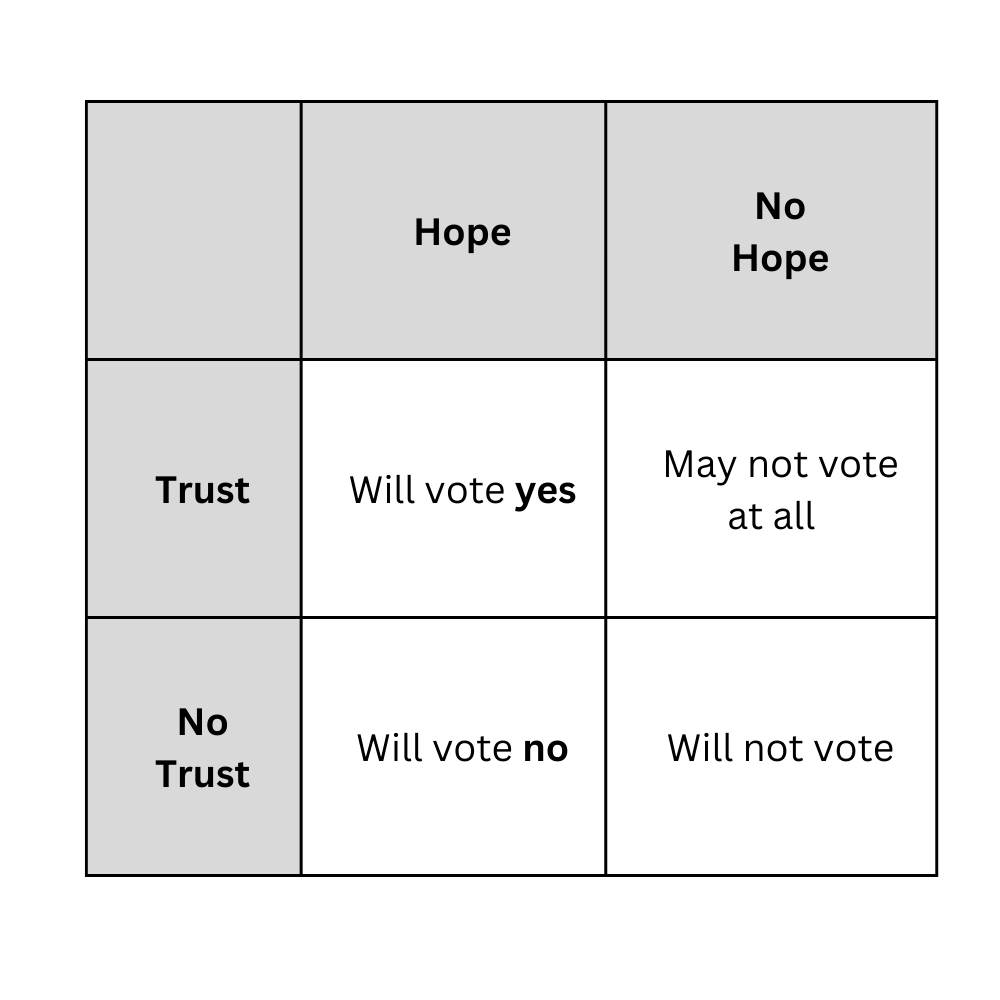

When members vote on ratification of a contract, the main issue is trust—whether in the contents of the deal, the process, or both.

People may vote yes because they generally trust the leadership—or vote yes (or don’t vote) because they do not hope for anything better.

But there are also people who have hope and think that the leadership could have done better. These are the people who may vote no. A vote no campaign indicates a substantial level of active rank-and-file distrust of the union leadership.

Then there are people who neither trust the leadership nor have hope. They probably will not vote at all.

The table at right shows the relationships of these groups.

A vote no campaign, therefore, has a double challenge. It has to instill hope for something better in people who have lost hope. Then, if the leadership has recommended ratification, it has to persuade these people to realize that hope by voting against their leaders’ recommendation. (In some cases, a no vote may be what the leaders want in order to strengthen their hand at the bargaining table.)

A VOTE NO CAMPAIGN IS A LOT LIKE ORGANIZING

On the heels of the Starbucks and Amazon workers organizing successes, workers are reluctant to settle for less than what they really want. This may put them at odds with local leaders who are leading negotiations and have brought back a tentative agreement.

Far from sending a message to the boss that the union is divided and vulnerable, a vote no campaign can be viewed as a sign of strength. In many ways it’s like union organizing: the “vote no” organizers have to expand the activist core.

The impact may be to send the existing bargaining team members back to the table with a more convincing threat behind them. It may cause some bargaining team members to give up and quit, and new ones to be elected or step forward.

It may strengthen a commitment to a continuing a job action, or initiate a new one. It can cause a positive change in the union leadership behavior toward better democracy. It can lead to new leadership with more rank-and-file support.

A fight going on inside a union also means that people understand that there’s something worth fighting over.

VOTE NO CAMPAIGNS HAVE A BROAD IMPACT

Win or lose, the campaign’s impact on the union can be far-reaching—as a look at 10 vote-no campaigns in various sectors shows.

At the University of California, in December members of UAW Local 2865 ratified contracts that will institute a pay disparity between campuses where there had not been one before. Despite significant pay increases, all workers will be earning way below a living wage and rent-burdened.

Nonetheless, activists on the campuses at Merced and Santa Cruz, where there was a strong vote no campaign, reported, “There is a much larger core of organized rank-and-file workers in our union now than there has ever been.”

As of this writing (in December) one bargaining unit of California Nurses Association nurses is on strike against Sutter Health at Alta Bates Summit Medical Center in the San Francisco East Bay—after voting no on a contract proposal that was recommended by their leadership but did not meet the standards agreed to at Kaiser and Stanford.

In the fall, unions representing the majority of railway workers (the SMART Transportation Division, the Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way Employees, and the Brotherhood of Railway Signalmen) voted down contracts and threatened to strike.

A strike by even one union would have caused gridlock on the railways, because all 12 unions that represent railway workers had agreed to honor the picket lines. President Biden intervened on December 9, imposing an agreement. The Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen, which had narrowly approved the contract, then voted to deny its incumbent president another term.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

In 2021, UAW members at John Deere voted to reject a tentative contract proposal and sent it back, twice. The first time, 90 percent of members voted no, leading to a month-long strike; after a second no vote, John Deere imposed a final agreement.

The main strike issue was the desire by the rank and file to eliminate various forms of two-tier. This contributed to the movement for members to directly elect the UAW national leadership, and to a change in leadership that is underway right now. (Some challengers for national office have won outright, and the presidency is headed to a runoff.)

Also in 2021, the majority of members of the International Alliance of Theatrical and Stage Employees locals governed by the main Hollywood and West Coast contract provided enough votes to vote down a proposed contract. However, in IATSE’s electoral-college-like ratification process, the contract was approved. The core issues were around health and safety and, obviously, democracy.

In 2018, more than 50 percent of UPS Teamsters voted against a contract offer, angry at the Hoffa leadership for allowing UPS to erode the gains of the historic 1997 strike. Because their constitution allowed a no vote to be overruled without a two-thirds supermajority, the leadership declared the deal ratified anyway. The reaction to this contributed to a change in national leadership in 2020, when UPS-based locals voted overwhelmingly for the Teamsters for a Democratic Union-supported Sean O’Brien slate.

In 2012, teachers in in Chicago were out on strike and their bargaining team brought a tentative agreement to the union’s Delegate Assembly. The Delegates refused to end the strike until the membership had time to read the whole contract proposal. Teachers sat on the picket lines, reading until they were satisfied.

Looking back further: In 1999-2000, engineers represented by the Society of Professional Engineering Employees in Aerospace struck against Boeing and rejected its contract offers three times. During the strike, union membership grew from 40 percent of the workforce to 65 percent.

The 1999 vote by the California Faculty Association membership in the California State University system to reject a tentative agreement led to a change in the bargaining team, the union leadership, and the culture of the union—resulting in credible strike threats and large contract improvements for the majority-contingent faculty workforce.

Perhaps the most famous vote no campaign was the 1985-’86 strike of Local P-9 of United Food and Commercial Workers strike by meatpacking workers at Hormel in Austin, Minnesota, the focus of the film “American Dream.” The UFCW leadership came back with a proposal that included concessions. One of the UFCW staffers who tried to shut down the vote no campaign, Lewie Anderson, later became a leader of a union reform caucus.

BROADER THAN JUST ONE UNION

Vote no campaigns may seem to be mostly about what’s going on in one single union, but they can inspire other related bargaining units in that industry or geographic region to ask for more or be more class-conscious. When there are a lot of workforces voting no, saying, “We can get more,” the level of the whole movement rises, changing the terrain of struggle.

This is why all these vote no campaigns deserve publicity. Like all organizing, no effort is ever wasted—even if a particular vote no campaign loses the vote.

Helena Worthen and Joe Berry are veteran labor educators and contingent faculty activists. Their latest book is Power Despite Precarity: Strategies for the Contingent Faculty Movement in Higher Education.