When Workers Swapped Segregation for Solidarity

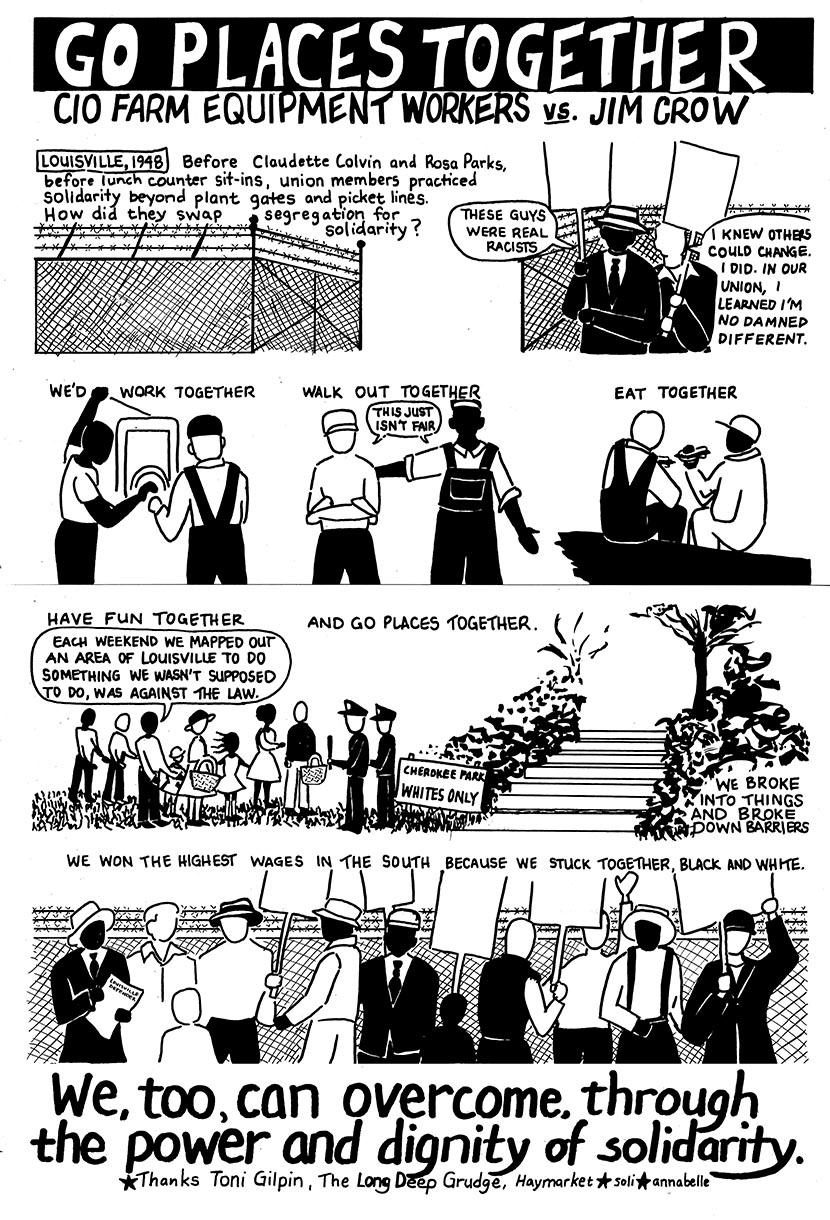

This detail from the comic below celebrates the solidarity between Black and white farm equipment workers in Louisville who struck together and socialized together, winning the highest wages in the South and challenging segregation beyond the workplace too. Graphic: Annabelle Heckler

Solidarity: we celebrate it in song, emblazon it on picket signs, and insert the word into Twitter hashtags. Inducing workers to overcome divisions and unite as a class, however, is far easier said (or sung about) than done. In our current polarized climate, solidarity may seem like an especially elusive goal.

But as a historian I can say: for organizers things have been tougher. In late 1946, corporate giant International Harvester (IH) opened a tractor factory in Louisville, Kentucky, joining the exodus of capital to the low-wage, and far less unionized, South. The Farm Equipment Workers (FE), one of the industrial unions that arose during the 1930s, already represented IH workers in Chicago and other Midwest locations.

In Louisville the FE—as opposed to the other unions competing for recognition at the new IH facility—made interracial equality central to its organizing drive. This was a risky strategy in still-segregated Louisville, since the vast majority of the 7,000 employees at the plant were to be white, steeped in the toxic traditions of white supremacy.

“We had hillbillies, that’s all we had,” said Jim Wright, one of the first Black employees at the Louisville plant. “And those kind of guys were real racist.”

Comic: ‘Go Places Together’

by Annabelle Heckler

The day-in, day-out "lived solidarity" that won raises and broke down barriers of segregation comes to life in Annabelle Heckler’s new comic “Go Places Together.” Click the image to view the comic full-size.

See more of Annabelle Heckler's work at @annabelleheckler on Instagram.

Yet in mid-1947 the FE handily won the representational election at the Louisville plant. The FE local there would go on to prove exceptionally cohesive and combative, as workers regularly stood together and struck back against IH management. They took their struggle for justice into the community, as FE members, both Black and white, battled segregation in Louisville’s parks, hotels, and hospitals. And they defied social norms, as Black and white workers from the IH plant began socializing together off the job.

In the Jim Crow-era South, the FE had instilled in its members what Wright called “a religious feeling of them sticking together.” How was this possible?

UNFETTERED DISCUSSION

The answer lies in the radical ideology that defined the FE. Many of its key leaders, both national and local, were connected to the Communist Party. The FE’s left-wing orientation resulted in a demonstrable commitment to racial equality, especially noteworthy in a union with a membership that was 85 percent white.

The FE fought to open skilled jobs to African Americans and won contract terms like plant-wide seniority that most benefited Black workers. From 1946 on, the FE’s leadership included a Black executive board member and a Black vice president. That was a track record unmatched at the time, even by unions that had many more African Americans in their ranks.

This helps explain Black support for the FE, but these same achievements could have alienated racist whites. To win them over, FE organizers in Louisville stressed the benefits that only solidarity could achieve. “The Southern bosses had for generations played white against Negro,” FE literature read. “There was a direct connection between this and the fact that Southern workers were the lowest paid in the country.”

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

However, the union did more than just pass out flyers. At frequent meetings, “it wasn’t just up-front stuff, of the organizer giving big speeches,” said Sterling Neal, a Black worker who became a leader of the Louisville FE. Rather, “workers were encouraged to discuss freely the questions they had on their mind.

“Sometimes there was objection openly on the part of white workers to the union’s policy of no discrimination,” Neal said, but “on many occasions the white workers who understood this question a little better challenged them on the floor.” These unfettered, sometimes difficult conversations solidified Black and white support for the union.

LIVED SOLIDARITY

But sustaining solidarity requires regular practice. The left-wing FE eschewed cooperation with management in favor of constant confrontation, and FE members engaged in exceptionally high levels of walkouts between contracts; the Louisville plant became especially strike-prone.

These actions proved effective at safeguarding and improving wages and working conditions. As Black and white workers walked off the job together, interracial unity became not an abstract construct but a regular exercise that delivered tangible benefits.

The radical FE modeled what could be called “lived solidarity”: the belief that day-in, day-out collective struggle—not just sloganeering—is essential to forging indivisible working class power. Through it the FE profoundly transformed workers who had been “real racists”—the sort that some today might label “deplorables.”

That was no easy task then, and it isn’t now. But the FE’s example makes clear that with a mix of persistence, patience, and rank-and-file militancy, it can be done.

You can learn more about the FE in Toni Gilpin’s book The Long Deep Grudge: A Story of Big Capital, Radical Labor, and Class War in the American Heartland.