Save the Program

Its ironic that the administration failed to get any feedback from the student body or alumni.

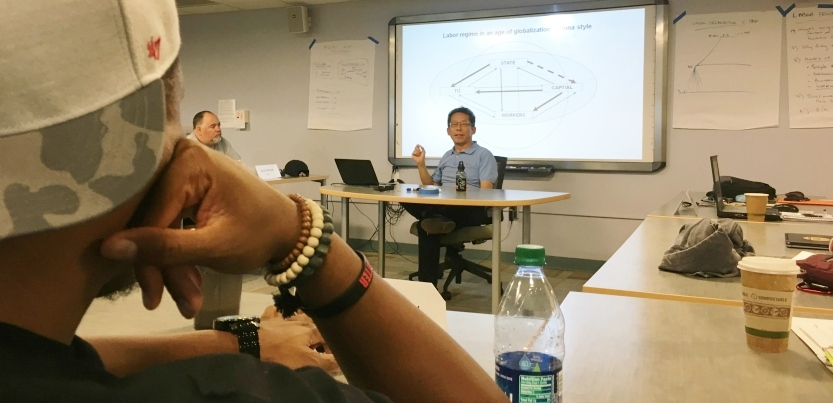

On the eve of Labor Day, students and alumni of the University of Massachusetts Amherst Labor Center discovered that the program was under attack. Photo: Chris Brooks

On the eve of Labor Day, students and alumni of the University of Massachusetts Amherst Labor Center discovered that the program was under attack.

Professor Eve Weinbaum, the center’s respected director, alerted alumni and students by email that she was being ousted, and that the university administration was slashing funding for many aspects of the nationally recognized program.

It’s the latest blow in a volley against labor education programs. A 2015 report by Helena Worthen for the United Association for Labor Education found that in recent years, 34 of the 53 programs across the U.S. have either lost staff or outright disappeared.

The report identified right-wing think tanks like the Freedom Foundation and the Mackinac Center as key players in the drive to eliminate these programs, especially at public colleges and universities.

Founded in 1964, the UMass Labor Center in Amherst is one of the most respected labor education programs in the U.S. It has trained generations of activists in collective bargaining, research, labor law, organizing, and labor economics.

Its limited-residency program in union leadership and administration, launched in partnership with the AFL-CIO in 1996, gives union activists across the country the chance to pursue a master’s degree in labor studies while working full-time. It offers rank and filers both practical training and a window onto bigger-picture issues in the labor movement.

The attacks are nothing new. Back in 2005, while UMass was facing system-wide budget cuts, faculty member Stephanie Luce observed that the Labor Center was the only department singled out to be cut outright.

The chancellor of the university at the time commented that unions should fund the Labor Center themselves, if it was so important to them. The Boston Globe cited his view that Massachusetts had a “public-dependent” mentality. But the Labor Center mobilized support and managed to survive.

The current cuts will end teaching and research assistantships and externship positions for full-time graduate students. In the past, every student in the program had access to one of these positions. This will make it very difficult for working-class students to attend, and nearly impossible to recruit new students.

The center will lose its full-time administrator, and will have no dedicated staff to run the program. This year’s budget eliminates the funding for part-time faculty, including instructors who have taught required courses for many years and have become essential.

Current faculty are not being given the time or resources to do the required administrative work for Labor Center programs. Nor can the three core faculty members fill the void created by the elimination of the part-time faculty.

The union members whose jobs are impacted by these changes include graduate employees (Auto Workers Local 2322) and faculty (a local of the Massachusetts Teachers Association).

The university administration ousted Weinbaum from her role as program director and announced that it will choose the next director, usurping control from the Labor Center’s independent governing committee.

According to Weinbaum’s email, the administration justified the cuts on the grounds that the residential program was not a “revenue generator” for the university.

All that will remain is a skeleton of the Labor Center’s offerings—a scaled-back version of the limited-residency program and an extremely truncated version of the residential program.

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

UMass officials seem to have prepared for a backlash. In a canned response to emails from concerned alumni, students, and allies, Dean John Hird of the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences denied that the center was under attack, claiming, “The Labor Center’s future is bright.”

But in an interview with the Boston Globe, Hird acknowledged the cuts: “People can come back when, hopefully, we’ve really bolstered the program and the enrollment grows and resources follow where the students are.”

“The administration’s actions do not match their rhetoric,” says Rebecca Givan, a labor studies professor at Rutgers who has been a visiting faculty member at the center for many years. “If they really intend to support the Labor Center, then they should not be withdrawing financial support. It’s also a major concern that the university would impose curricular changes, such as removing required courses.”

Pat Crowley, one of the authors of this article, was at work driving a Zamboni in a small-town hockey rink in eastern Massachusetts when he got the call to head out west, all the way to Amherst, for an interview about joining the Labor Center as a graduate student.

Despite the fact that he did the interview still wearing his work overalls—or maybe because of that—Pat was admitted to the program. To this day, in his work as an organizer and representative for the teachers union in Rhode Island, he refers back to his training at the Labor Center, particularly on the importance of rank-and-file activism.

The other author, Sarah Markey, is enrolled in the Labor Center’s limited-residency program. This gives her time to balance her work as a union organizer, life with two young children, and the pursuit of an advanced degree. What she appreciates the most about the experience is the high quality of the curriculum and faculty.

Michele Evermore, on the staff of the health care union SEIU 1199 New England in Connecticut, graduated from the residential program in May. “Coming to the Labor Center was one of the best decisions I could possibly have made at this point in my career,” she said.

“Because of the comprehensive education I received, I am now at a great union local, and feel like having a real understanding of labor history and how all the parts of a union work together to build worker power has made me not just better at what I do, but a better and more thoughtful person.”

As Worthen wrote in her UALE report, “Higher education has become, in many instances, just another way to produce inequality. The content of labor education confronts this directly. What people learn in labor education classes is how to fight back against the forces that intensify inequality, whether at the bargaining table or in communities.”

Given the vital role the Labor Center plays in the vibrancy of the labor movement both regionally and nationally, and its willingness to continue to teach skills that don’t conform with neoliberal norms, such as collective bargaining skills, strategic organizing techniques, and corporate campaign research, it’s essential that we defend it.

Past students are showing their support in an online petition. “I graduated from the program over 30 years ago, and have spent all of those years in the labor movement,” wrote Clio Bruno of Tampa, Florida. ”Reducing access to the program based on ability to pay would be shameful.

“In these times of growing inequality resulting from the weakening of the labor movement, it is more important than ever that there be open access to a program that teaches people how to struggle for economic and social justice.”

To join this resistance and help restore funding and support for the Labor Center, check out the campaign’s website and Facebook page, and sign the petition.

Patrick Crowley and Sarah Markey are staffers at NEA-Rhode Island.

Its ironic that the administration failed to get any feedback from the student body or alumni.