Adidas Caves, Pays Garment Workers What They’re Owed

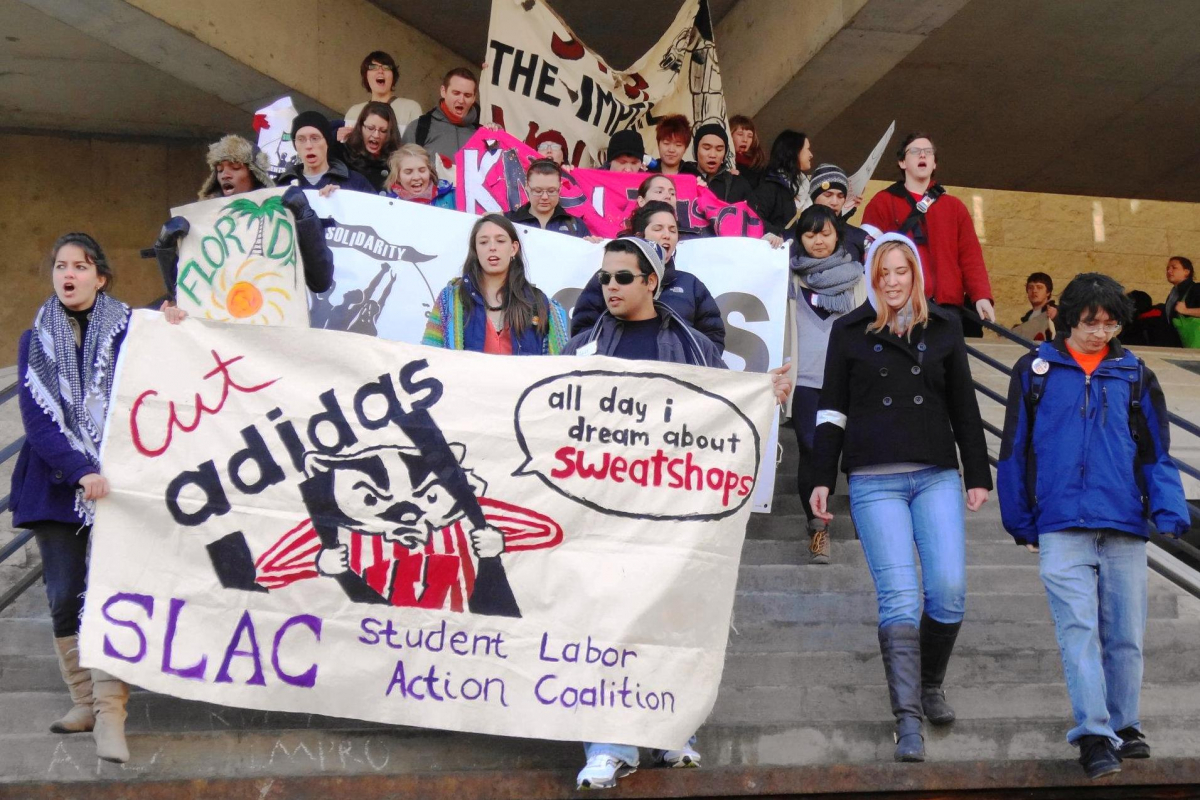

After the largest collegiate boycott of a top-three sportswear company in history, Adidas has agreed to pay the severance it owed 2,700 former workers of the PT Kizone garment factory in Indonesia. Seventeen colleges and universities ended their relationships with Adidas. Photo: United Students Against Sweatshops.

Seventy students from across the U.S. got on an emergency conference call last Tuesday for news they’d been waiting over a year and a half to hear. Mariela Martinez, a student at Brown University, told the listeners, “The PT Kizone workers have reached a historic agreement with Adidas... They’re going to receive the severance that they’re legally owed!”

All it took was an international campaign that engaged workers, students, and activists from around the world.

Legally mandated severance pay is the norm in most apparel-exporting countries. Employers pay severance because of the absence of unemployment benefits. When garment factories close, legally mandated severance is all workers have to rely on. And close they often do, sometimes without notice, because of the relentless price pressure on factory owners from Western brands and retailers.

For two years the 2,700 former workers of the PT Kizone factory in Indonesia, which made apparel for Adidas, Nike, and the Dallas Cowboys, had insisted that Adidas pay them the $1.8 million they were entitled to under Indonesian law.

The other brands that sourced from PT Kizone had paid their shares of the severance soon after the factory closed in 2011. Members of United Students Against Sweatshops (USAS) noted this was an about-face for Nike, which in 2010 had resisted paying severance to workers in Honduras. Nike eventually paid those workers $2 million after several colleges severed their contracts—and this time the brand chose to pay right away.

Bad Adidas

Encouraged by the difference that coordinated student campaigns were making in the garment industry, USAS decided to confront Adidas through the “Badidas” campaign. Students set out to undermine the race to the bottom, in which owners of subcontracted factories cut and run with impunity, and brands several degrees removed from the workers deny all responsibility.

In the summer of 2012, two USAS members went to Europe to contact groups that might be able to pressure Adidas, which is a German company. Throughout the campaign, organizations such as People and Planet, Labour Behind the Label, War on Want, and the Clean Clothes Campaign participated in transatlantic days of action against Adidas, at one point staging a protest outside every major Adidas store in the U.K. These groups also provided valuable information about the European consumer market to their U.S. counterparts.

“Our European allies played a huge role,” said Billy Yates, a student at the University of Texas. “We knew if we were going to run a truly international campaign against a multinational corporation, we would have to get groups from other countries to join us.”

With European organizations holding Adidas’s feet to the fire on its home turf, students found ways to shine a spotlight on the company’s wrongdoing in the U.S. These included flyering at basketball games where Adidas-sponsored teams were playing and going after its celebrity spokespeople, most notably Selena Gomez.

I participated in one such action: during an Adidas fashion show, I walked across a runway to hand Gomez a flyer detailing her sponsor’s violations of worker rights. These demonstrations garnered attention, not only in progressive media, but also in fashion and celebrity gossip outlets.

University Sweat-free-shirts

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

The most important leverage students have over apparel companies is through university contracts. Dozens of campus groups campaigned for their schools to drop Adidas. The groundwork was laid over a decade ago when USAS began pressuring schools to adopt the Worker Rights Consortium’s code of conduct, which stipulates brands must adhere to labor laws in the countries where they produce. Students demanded that their schools uphold the code they had agreed to, and 17 colleges and universities ultimately ended their relationships with Adidas.

Back in Jakarta, Indonesia, the workers took their protests to Adidas offices, the German embassy, and the courts. Former PT Kizone workers came to the U.S. to speak at schools across the country, attending campus rallies and meeting with administrators.

When the University of Wisconsin brought Adidas to court to get a declaratory judgment on whether the company had violated its code of conduct, the PT Kizone workers provided a brief that weighed in on the matter—marking the first time that a brand’s subcontracted workers, half a world away, directly confronted their real employer in a court of law.

The Badidas campaign led to the largest collegiate boycott of a top-three sportswear company in history, and it is the first time Adidas has caved to pressure over the rights of garment workers. Now Nike and Adidas, the two largest sportswear brands in the world, have been forced to acknowledge that they cannot walk away when their contractors deprive workers of legally earned money.

In addition, the successful intervention of the PT Kizone workers’ union in the University of Wisconsin lawsuit has implications for other subcontracted workers who want to force their ultimate employer to take legal responsibility for abuses.

A win like this is critical right now. The tragic factory collapse in Bangladesh last week shows how deadly the current garment manufacturing model is. As more work is subcontracted, both in the U.S. and across the world, workers and allies are developing strategies to confront the companies at the top of the supply chain.

Earlier this year, workers from Bangladesh, Nicaragua, and other garment-exporting countries formed the International Union League for Brand Responsibility. The League’s first declaration noted that brands like Adidas profit from “the decentralized global manufacturing model,” and the organization vowed to coordinate across borders to force brands to take responsibility for garment workers’ conditions.

At the end of the USAS call announcing the Badidas victory, students joined one of the former Kizone workers, Aslam, in a cheer they had learned through the workers’ visits to their campuses—Hidup buruh! Long live the workers! Hidup USAS! Long live USAS!

Caitlin MacLaren is a junior at New York University and a regional organizer for United Students Against Sweatshops.