Striking Is in the Air at Boeing

A Boeing worker in Renton, Washington, assembled a 737 MAX wing. The last full contract was negotiated in 2008, with a 58-day strike. Workers are ready to go “Out the Door in ’24” due to low pay, forced overtime, the 2016 elimination of the pension.

Mondays and Wednesdays are loud at the vast Boeing factory in Everett, Washington. As the Machinists’ contract campaign heats up, the workforce has been serenading management at lunch with air horns, train horns, and vuvuzelas—plus chants of “Out the Door in ’24.”

Forty miles south, in Renton, where workers construct the moneymaking 737, second shift workers have used their meal breaks to blast Bluetooth speakers at top volume with ’90s rap, death metal, ’80s pop, and opera—all simultaneously, said Jon Voss, a 13-year mechanic in the wings building. The resulting racket “really drove management and HR nuts.”

The Boeing contract expires September 12 for 31,000 members of Machinists (IAM) District Lodge 751 in Washington and 1,300 District W24 members in Gresham, Oregon. The last time a full contract was negotiated was 2008, with a 58-day strike.

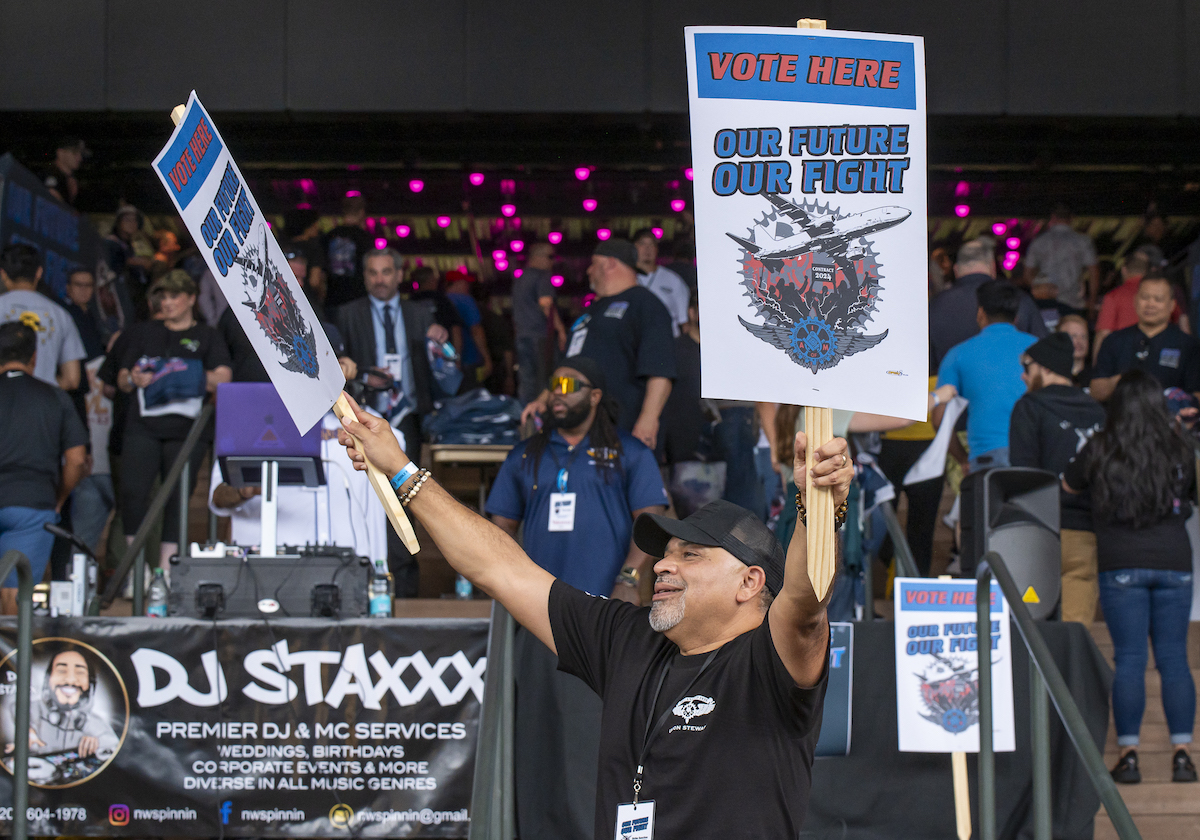

A workday rally July 17 at the Seattle Mariners baseball stadium drew 25,000—including a procession of 800 motorcyclists—and 99.9 percent of members attending voted to sanction a strike, the first step towards a walkout under the Machinists constitution. They will vote again when they see a proposed contract.

DEMORALIZING PAYCHECKS

At issue are starting wages that barely match nearby fast food jobs, the replacement of a defined-benefit pension 8 years ago with successive tiers of cheaper and cheaper 401(k)s, and mandatory overtime that eats up weekends and leaves workers mentally and physically spent.

“It’s driving people insane, 10- to 12-hour days, 19 days in a row,” said Voss, a senior steward.“It’s exhausting people, to the point we’ve had people pass out at work.”

It’s a sad decline for a company that used to be the golden ticket in the Puget Sound area.

“Used to be nobody would talk bad about Boeing,” recalled Edwin Haala, a heavy structure mechanic who started in 1996. “Now, we don’t want our kids to work there.”

“The best in the industry used to crawl over shattered glass just to get an interview to work here,” said Voss. “And now the company is begging high school students to apply.”

Starting pay at Everett is around $19, while nearby Seattle’s minimum wage is $19.95. “There’s a retailer right across the street from one of the factories that says ‘we’ll pay you more than Boeing,’” said Voss.

Wages are slow to rise with experience, reaching top rate after six years, but even that is not a family-supporting wage. Voss said he has co-workers who can’t afford to move out of their parents’ house, or have four roommates, or are living in their cars. “It’s demoralizing, it crushes their spirit and new folks hate the company because of it.”

The nickel-and-diming of the workers is particularly galling, Haala said, because for Boeing, labor accounts for only 3 to 5 percent of the cost of an airplane.

Low pay means people work overtime to pay their bills, but mandatory overtime is much hated.

“If for whatever reason you’re behind on your job, which has lately been because of parts problems, they can designate you for up to two hours pre- or post- shift,” said Ky Carlson, an assembler with five years in who works on the 777 at Everett. After working 19 consecutive 10- or 12-hour days “you can get a single weekend off” she said.

Mandatory overtime is capped in the contract at 112 hours over three months—an average of nine extra hours a week. The cap had been 128 hours, but the union won a reduction during effects bargaining in 2018.

DORKS IN CHARGE

Boeing has been in the news a lot, most of it bad. Two 737 MAX 8 crashes in 2018 and 2019 caused by faulty flight-control systems killed 346 people. The fatal flaw resulted from bad design on top of a workaround designed to bypass the government certification required for a new aircraft design.

Just as panic over that issue was dying down, a door plug blew out of an Alaska Airlines 737 MAX 9 flight after takeoff from Portland January 5.

Production halted in Renton and then resumed at a snail’s pace while Federal Aviation Administration inspectors flooded the plant, “followed closely by Boeing’s lawyers,” Voss said.

Federal regulators again dictated a safety reset to the company, and Boeing ousted CEO David Calhoun. Workers are skeptical, but noted that at least the new CEO is an engineer. “We don’t need finance dorks running this place,” said Voss.

The latest humiliation has been Boeing’s Starliner, which took two astronauts to the International Space Station June 6 for a one-week stint, but propulsion problems mean it can’t be trusted to bring them back. Now it forlornly occupies one of the station’s docks, while eight station crew cram into a living area designed for six.

Workers say the quality problems result from a focus on profit at the expense of quality, and hiring managers whose only expertise is in pressuring workers.

In recent years, rather than promoting shop floor leaders who thoroughly know the job, the company started hiring outside people to manage, Haala said. He recalled one who came from managing a Blockbuster video store.

“They were removing quality inspections,” IAM District 751 President Jon Holden told the Valley Labor Report, “shifting it over to where a mechanic might inspect their own work or inspect other mechanics’ work, and I believe this started to take a toll.”

CAN’T KEEP WORKERS

Workers also cite a brain drain. The 737 MAX 8 catastrophe shut down production at Renton, and then the pandemic tanked demand. Along with layoffs, many experienced long-timers retired.

Hearings on the door-plug episode revealed dizzying turnover numbers. Machinists Business Agent Lloyd Catlin testified at a National Transportation Safety Board hearing August 6 that the company told him for the Renton facility, “60 percent of the Boeing workforce, including management, had less than two years at Boeing Company.”

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Experienced mechanics have other options in the area—SpaceX, Blue Origin—or they get experience at Boeing and leave to work for an airline fixing planes, said Haala. He retired after 25 years constructing floor grids—“the backbone of the aircraft”—and now works with the union’s mentorship program helping new workers on the shop floor.

When he started mentoring, Haala said, front-line supervisors were delighted to have him back in his old shop at Everett. But despite the desperate need for experienced hands, higher-level managers sent him elsewhere. “My area, I could tell you every fastener… if I go into another area, it’s so specialized, it would take me a year.”

Voss said six people resigned in the past week in his shop in Renton, where they install electrical and hydraulic systems in 737 wings. “They can’t keep people in the door.”

His area is particularly bad for turnover “because of the absolute pressure that is put on people for such little return.” And Voss said their managers have a counterproductive “Just figure it out. Don’t do it wrong!” mentality.

“Our jobs, our legacy, and our reputation are on the line right now,” Holden told the stadium crowd July 17. “We are fighting to change this company and to save it from itself.”

The union wants to be able to grieve more changes “to ensure we aren’t undermining the foundation of our manufacturing system,” said Holden.

High turnover could be an issue for the union. Haala estimated that 75 percent of the workers haven’t been through a strike, since the last one was in 2008.

But newer workers said they’re excited by the campaign and the prospect of winning the union’s demand of a 40 percent wage increase over thee years, along with a real pension.

“Seasoned folks, we want our pensions back, and that is the hill that many of us are ready to die on,” said Voss. “And a lot of new folks are learning what a pension is [from us] and they’re saying, ‘Well, I want that too!’”

JOBS BLACKMAIL

The company has repeatedly used jobs blackmail to wring concessions. Under threat of moving 737 MAX production, the union extended the contract in 2011 and then agreed to a disastrous mid-contract re-opener in 2013 when the company threatened to move production of its new wide-bodied jet out of state. The workforce rejected that disastrous contract extension by 67 percent, booing the leaders who brought it to them.

But the national union pushed it at the workers again, over the objections of the local bargaining committee, and it squeaked past with 51 percent in a January 3, 2014 in-person vote with low turnout. Many workers were still on vacation because of a plant shutdown for the holidays.

As a result, the pension was frozen in 2016—current workers were left with whatever they had accrued, and newer workers were given a 401(k) that now has several tiers of increasing stinginess. Wages stagnated and health care costs rose. And the contract was extended to 2024.

After that, the Machinists changed their constitution so officers can’t negotiate extensions or modifications to the contract without a specific OK from the membership. Riding the frustration, Holden was elected in 2014.

This time there have been no threats to move work. Workers say this is because the company is behind on filling orders for planes. “Boeing’s in no position to act tough and threaten workers with moving work because they have so many projects on fire or late,” said one Everett-based worker.

On August 17 the bargaining committee reported to members that on pensions, “so far, the company’s proposals fall drastically short of what our members deserve… This is a fight we cannot and will not lose.” The union wants the pension back with retroactive contributions for the eight years it was frozen.

STRIKE READY

“With how much people want the pension back, people want to strike, cause they know Boeing’s not going to offer them that right out of the gate,” said Carlson. Workers said they’d been saving up money in preparation.

Managers are also preparing for a strike. Workers in Everett and Renton said supervisors are being tasked by their bosses to get their production certificates in order with the idea that they would build planes in case of a work stoppage. This didn’t work out well last time, Haala recalled. “Last time on strike a lot of issues came up and the FAA told Boeing ‘You’re not working on those airplanes.’”

But even if production doesn’t go forward, it could go backward. In 2020, when Everett shut down for three weeks due to the pandemic, it was a job just to protect the half-built planes from humidity buildup and other degradation.

In addition to pay, pensions, overtime, and cost shifting on health care, the union is trying to get the company to promise to build its next plane in the Puget Sound area.

“We need jobs for 50 years, not four years, and the only way that’s going to happen is if Boeing makes workers a part of its vision for the future,” said Holden.

Does Boeing Secretly Want a Strike?

There is some chatter at work and on worker Facebook pages that Boeing actually would like a short strike because many plane deliveries are late and it is having to pay contractual penalties to the airlines as a result. The contracts allow for penalties to evaporate in case of a job action.

But workers I spoke to were skeptical. Boeing doesn’t sell planes like cars on a lot, said Ky Carlson, an assembler in Everett. “Throughout the manufacturing process, they have these things called milestones, and every time they hit a milestone, that’s when they get a payment from the airline for the plane.” A strike would immediately create cash flow problems for the company.

Another argument circulating for Boeing wanting a strike is that it would help the company accumulate parts that are currently in short supply and are slowing production. But even when warehouses full of inventory piled up during the pandemic, there were still massive delays, said Renton steward Jon Voss. “Everything was in place but the workforce.”

And, “To receive parts, you need people to stock the parts, take inventory, and they’re all IAM members,” said Carlson. “Or if not, they’re Teamsters.”

The Teamsters demonstrated solidarity during a recent lockout of Boeing firefighters when they refused to deliver across the firefighters’ picket lines.

A long strike could create conditions like the pandemic when some parts suppliers went bankrupt. “They’re just now starting to recover from the chaos that Covid was,” said Carlson. “For that to basically happen all over again would be a nightmare scenario.”