Nurses, Bus Drivers, Teachers: Facing Violence on the Job

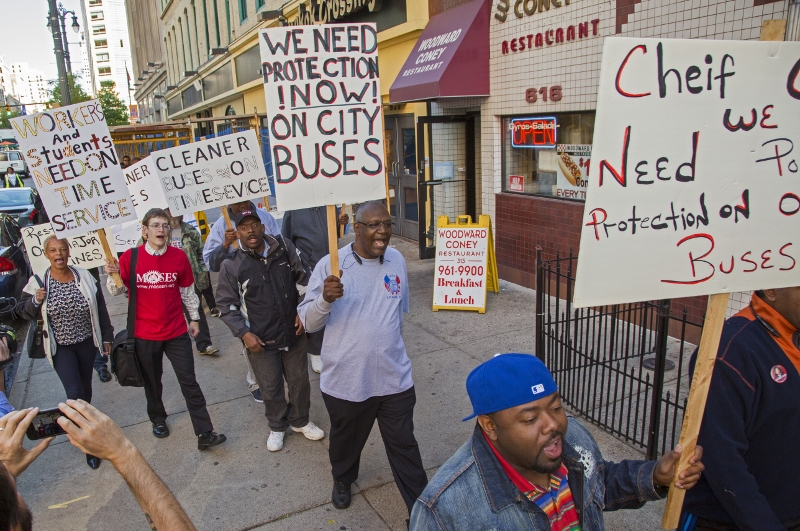

Detroit bus drivers demand measures to protect them from assault. Transit employers resist even simple changes such as Plexiglas shields or training on how to cope with belligerent riders. Photo: Jim West, jimwestphoto.com.

In a Milwaukee psychiatric hospital, a patient smashes a mirror and threatens to stab staffers with a shard if they come near. In Chicago, a student puts sulfuric acid in a teacher’s water when his back is turned. In Washington, D.C., a rider throws hot coffee on a bus driver. In New York City, subway workers are routinely spat upon. In Albany, New York, mail carriers request armed escorts because of random shootings in a neighborhood.

And the Occupational Safety and Health Administration investigated Brooklyn’s Brookdale University Hospital after a patient kicked a 70-year-old RN repeatedly in the head.

The nurse is in a coma and not expected to recover, according to Steve Schrag, who does hazardous materials training for the victim’s union, 1199SEIU. “It’s an exaggerated version of what happens every day,” he said. “Our members are so livid at management’s callousness.”

Did You Know?

OSHA says nearly 2 million workers report workplace violence each year, but many more cases go unreported.

Homicide is the leading cause of death for women in the workplace and assaults are the fourth-highest source of fatal on-the-job injuries overall. There were 506 workplace homicides in 2010.

A big chunk of the working population deals every day with one or more of the factors OSHA cites as raising the risk of violence:

- providing services or care

- exchanging money with the public

- working with volatile, unstable people

- working alone or in isolated areas

- working where alcohol is served

- working late at night

Just from February through early April this year, OSHA found, workers at Brookdale were assaulted by patients or their family members 40 times. The agency took the rare step of charging the hospital with a “willful” violation, the most serious level. It levied a $78,000 fine and ordered Brookdale to take steps to defend employees from assaults.

But in far more cases, when workers are hurt, management suffers no consequences.

“Whenever a worker dies on the job, someone should go to jail,” Schrag argues. “OSHA can give citations and fines, but who pays the fine? The CEO will not pay the fine.”

CUTS FUEL RAGE

In some industries workers say physical assaults are increasing—and cutbacks in public services are a prime reason. Frustrated clients take their anger out on the nearest punching bag, the public employee.

“Service is worse and the price is higher,” says Larry Hanley, president of the Transit Union (ATU), which represents bus drivers, “and the driver has to deliver the bad news every two blocks.” (For how drivers and riders are fighting cuts, see “Everyone Get on the Bus.”)

In particular, workers cite cutbacks to services for people with mental illness. Deprived of both institutions and meds, they may wander the streets or public transportation, or end up in emergency rooms.

“We’re short-staffed. People come to the hospital very, very sick these days,” says Bernie Gerard, vice president of the Health Professionals and Allied Employees union in New Jersey. “Families are wanting answers, they can’t get hold of the doctors, the families’ needs get shortchanged—and they act out on someone nearby.”

When Hotel Guests Attack

After the notorious incident where a hotel housekeeper accused International Monetary Fund head Dominique Strauss-Kahn of raping her in a New York hotel room in 2011, her local won protections for hotel workers citywide.

Union housekeepers and room service attendants are now given “panic buttons” to summon assistance—and management may not use the devices for any other purpose, such as tracking their work.

If workers feel unsafe entering an occupied room, management must provide someone to accompany them. And management pledged to respond promptly to worker complaints about guests, rather than disciplining the worker.

“The problem is worse at non-union hotels,” said Anne Marie Strassel of the hotel workers union, UNITE HERE, “not the guest behavior, but the extent that people feel they can come forward and management will respond. We can’t always control guest behavior, but we can control how management responds and how comfortable people feel about reporting hazards.”

Guillermina Mejia, a health and safety rep at AFSCME District Council 37 in New York City, notes that many of her union’s members “deal with enforcement-type activities or issuing penalties against a resident”: tax assessors, public health sanitarians who issue summonses to restaurant owners, food stamp workers who might have to deny eligibility, even librarians who ask patrons not to access inappropriate Internet sites.

“It can get very testy,” Mejia said. “Any area of enforcement is going to increase the risk of assault. Our tow operators who have to tow illegally parked cars are at high risk. People will try to use their vehicle as a weapon.

“When you’re in a uniform, you’re perceived as someone in authority. And a lot of our members wear uniforms.”

“If your train is late, you can’t take it out on the CEO. If a dog bit you that morning, you can’t spit on your boss,” says Steve Downs, who represents subway workers in New York. He’s noticed a “generalized level of hostility and anger among a part of the population.”

It’s possible that resentment is also fueled by politicians’ attacks on “greedy” public employees—they have pensions!—as when Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker called public workers the “haves” and everyone else the “have-nots.”

WHAT’S THE ANSWER?

There’s no easy solution to workplace violence. No one wants to work in a fortress surrounded by armed guards—and even that would be no guarantee. “I will never tell members you can get rid of all the hazards,” says Schrag.

But he suggests employers should acknowledge that attacks are always a possibility, and build in universal controls. Those can include physical changes to the workplace, avoiding working alone, personal alarm systems (a panic button), agreed-upon escape routes, training in how to de-escalate charged situations, and security guards.

Bus drivers have taken two approaches. One is Plexiglas shields surrounding the driver’s seat.

Transport Workers Union Local 100 in New York, for example, won retrofitting of older buses in its latest contract. “An enormous effort went into this,” said Downs. “Lobbying in Albany, trying to get legislation. A ridiculous amount of time to get them to bolt a piece of Plexiglas up.”

Why Is Management Indifferent?

Stories abound about management’s apathy towards attacks on workers, and even hostility to hearing about the issue.

In hotels, the bias is obvious. Management cares more for even its obnoxious guests—so many of them traveling businessmen—than for its low-paid housekeepers, who are usually women of color.

Debbie White, president of a nurses’ local at Virtua Memorial in New Jersey, says the coddle-the-customer mentality extends to health care.

When a patient’s family member threatened a nurse in the ICU, “she called security, and they escorted him out,” White recalled. “But later on, in the interests of the Medicare regs that say you have to have patient satisfaction or you don’t get reimbursed, they allowed the man to come back in. They said he had a right to see the patient—although she had a restraining order on him.”

Larry Hanley of the bus drivers union remembers when a rider threatened him with a knife. “I told [management] I needed protection on the bus. ‘You got protection,’ he said: ‘$50,000.’

“That was our death benefit.”

Managers also cover up incidents. English teacher Jerry Skinner says administrators at his Chicago high school wanted to “make themselves look good by making sure that misconduct records were very low,” so they simply changed their procedures for reporting, in violation of district rules.

“We saw a document lauding our principal for reducing these incidents from 2,900 to 1,100,” Skinner said.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Most health care managements “don’t even want to have the discussion, because it raises issues of control of the workplace. They don’t want to acknowledge that the union has a good idea,” says Steve Schrag of 1199SEIU.

“Plus there’s the mentality that violence is just part of the job. And their tolerance toward members being hurt is really not much different from 100 years ago: workers are replaceable parts, so they don’t see any particular reason to care about a particular worker getting injured.”

—Jane Slaughter

The downside, of course, is cutting off social interactions with passengers. And “it’s hard to be in that little enclosed space, it makes your driving space even smaller,” says Kewana Battle-Mason, who drives a bus in D.C.

Some European bus systems and some coach buses here have a driver-side exit on the left, to escape a threatening passenger. But American unions have not won this expensive solution.

The other thing drivers do to protect themselves, with management’s tacit agreement, is not to be overly insistent when riders resist paying the fare.

In the past transit managements would require drivers to aggressively pursue fares. After a driver’s murder and “a lot of struggle and bad press,” says Tim Schermerhorn of Local 100, “now all the operator is required to do is request the fare.”

But, Hanley says, training for drivers in how to handle angry or defiant passengers is very limited.

In the wake of the brutal incident at Brookdale Hospital, Helen Schaub, who works on policy and legislation for 1199SEIU, laid out some solutions for hospital workers. One is personal alarm systems, as recommended by OSHA.

Another is better communication among hospital departments. The man who attacked the nurse was known by some workers to have psychiatric problems, yet other workers weren’t alerted to take precautions.

DON’T WORK ALONE

Not working alone would be a big help. With another set of eyes and ears, the nurse might still have been attacked, but not as seriously. “You shouldn’t have one worker in a long corridor with no one else in the corridor,” Schaub said. “Place the nurses’ stations so they’re able to quickly see what’s going on.”

But that implies full staffing, which hospital administrators resist as if the money were coming out of their own pockets. “We urge people not to work alone,” Schaub said, “but it’s not like you can call in another nurse to work your shift with you.”

After years of union lobbying, New Jersey has a model law requiring each health care or nursing home workplace to have a Workplace Violence Prevention Committee, with frontline staff making up half the committee. They are to assess risks, take steps to reduce them, and give annual violence prevention training. Workers are assured of no retaliation for reporting assaults.

But Debbie White, a nurse union local president, says implementation has been blocked by a hostile governor, Chris Christie, “a micromanager” who “puts a stop to anything that would interfere with his agenda.” The Department of Health simply does not enforce the regulations, she said.

The regs were still useful, however, when her union called OSHA. An investigation showed the employer had neither a real program nor training. When the agency issued “a stern warning, [administrators] were really taken aback,” White said. “They are so used to getting away with whatever.”

And when a threat happened soon after that, “security came right up and escorted the person out and said they wouldn’t be able to come back.”

MAKE A LAW AGAINST IT

Some public employee unions have tried to pass laws increasing penalties for assaulting certain categories of workers. Such laws usually mandate that management, or a joint committee, devise a plan for dealing with violence.

But such laws are of limited value. For one thing, said Hanley, a person who hauls off and hits a public servant is usually in the grip of “a private passion, somebody who got mad at that moment. They aren’t thinking ‘what are the penalties?’”

For another, prosecutors have proven very reluctant to pursue such cases. Although it’s a felony to assault a subway or bus operator in New York—and this fact is announced on signs and over the bus PA—Downs says his union “has spent 10 years trying to get district attorneys to prosecute violators to the fullest extent, and the DAs say no.”

After some brutal assaults, the local mobilized its resources to press for convictions with serious jail time. But the worst penalty was a year in jail for a passenger who severely beat a woman bus driver (the driver had told her she couldn’t bring her pit bull on the bus). “The legislation is there but it hasn’t made a difference,” Downs said.

As another way to pursue convictions, in its last contract the local won DNA kits on buses, to collect the saliva of those who spit on drivers.

IS WIN-WIN POSSIBLE?

Since many vulnerable workers are in the “helping professions,” they see the need for solutions that help their assailants, too.

Teachers in particular want to end the “school-to-prison pipeline.” A student who’s expelled or referred to the police for misbehaving at school has a far greater chance of being sent to jail down the line.

Teachers say being physically attacked by students is actually pretty rare, with verbal defiance far more likely. The assaults generally happen to other students. “We have a lot of really angry kids, and they have good reasons to be angry,” says Debby Pope of the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU).

Rebecca Solomon, recently elected to the board of the Los Angeles teachers union, says one solution is more counselors: “The students need one for academics and one for personal problems.

“And the school needs a therapist or psychiatric social worker—most have none, or one to two days a week. And then you have to spend the money to give teachers professional development time to figure out what their behavioral support plan is at their school.”

Students in urban schools run a gauntlet of security guards and metal detectors, and teachers unions are unlikely to say they should be taken out. But the American Federation of Teachers supports an intervention with more chance of rescuing students from snowballing violence: “restorative justice.”

Rather than “punishment or retribution,” says CTU’s Michael Brunson, “restorative justice does hold the student accountable, but it’s more concerned with restoring relationships with the community or class they have disrupted.” Tactics may include peer mediation, conflict resolution meetings, or peace circles, where students from warring groups participate in discussions led by a trained coordinator.

Nurses’ Conference On Hospital Violence

On October 9 a Pennsylvania nurses union, PASNAP, will hold a conference near Philadelphia, open to any nurse, on combating violence in hospitals. For information contact emily[at]pennanurses[dot]org.

Chicago Public Schools have “started paying lip service to restorative justice,” Brunson said. “But the way it was being rolled out, when a student acted out, they’d get sent to the principal’s office. Five minutes later they’re back in the classroom.

“I don’t know if they were just told to keep their suspension numbers down. But the idea went around among our members that restorative justice means ‘anything goes.’”

The union got a grant last year to work with a student group to pilot restorative justice in four schools. Chicago high school teacher Jerry Skinner spent 32 hours this summer in training. He says the community group involved in his school also supports the program. That’s critical for a union that’s made community partnerships key to its strategies.

“Restorative justice is good,” Skinner said, “but you have to fund it with trained personnel, and make sure it’s not just an additional chore put on teachers with no time to do it.”