Democrats Dodge Minimum Wage Increases, Activists Undeterred

A young man caught up with Congressman Bill Young at a Florida Fourth of July event this summer to ask whether he would support increasing the federal minimum wage to ten bucks an hour.

“How about getting a job?” fired back the Republican, who has served in the House for 41 years.

“I do have one. I make $8.50 an hour,” the activist replied.

Rep. Young seemed baffled. “Well, then, why do you want... why do you want… a benefit? Get a job!” he mumbled, edging sideways. The encounter, captured on video and posted online, got the congressman named “Loser of the Week” by a local paper.

This kind of thing happens all the time when conservative politicians are confronted about the minimum wage, says Jen Kern of the National Employment Law Project. Majorities of voters, even Republicans, support raising the wage floor, and politicians who oppose it sound mean and out of touch. On the flip side, those who support it win votes.

“This is a great issue to run on,” said Kern. “It’s a very cut-and-dried, ‘whose side are you on’ kind of issue.”

But no one is running on it this year.

POPULAR BUT IGNORED

Just a few years ago, Democrats were capitalizing on the issue’s popularity. Six states ran minimum wage ballot initiatives in 2006. All six passed with flying colors, and the measures gave a turnout boost to Democrats in off-year congressional races.

The momentum of those victories propelled Congress to raise the federal minimum for the first time in a decade, in early 2007. Barack Obama promised in 2008 to increase it again to $9.50 an hour by 2011.

Nothing doing. Four years later, the federal minimum still sits at $7.25, and Obama’s not talking about it. Since employers scuttled Missouri’s effort (see back cover), no state has a minimum wage increase on the ballot this fall, either.

It took a 30-city coordinated protest by unions and community organizations in July just to get congressional Democrats to make a symbolic gesture on the issue. They introduced a pair of federal minimum wage bills this year, only to let them die in committee.

Activists say it’s just another example of how deep-pocketed employers set the agenda in Washington.

“The Democratic Party, like all the rest, responds to the people who donate the growing sums they need to win,” said Chris Townsend, political director for the United Electrical Workers. “And labor is increasingly tapped out. We’re just kind of eclipsed.”

“It’s hugely popular, but it costs them money in their campaign funds, so they have to figure out which they need more, votes or money,” agreed Madeline Talbott, a member of Action Now, which is organizing low-wage workers and community members to raise Illinois’s minimum. “And mostly they want money, until it’s real close to an election.”

A widening gap. The real value of the federal minimum wage has been on the decline for decades. It’s now $7.25, but if the minimum had kept pace with inflation since 1968, it would be $10.59. If it had grown at the same rate as executive compensation since 1990, today’s minimum would be more than $23.

Two-thirds of new jobs in the recession-recovery era are in low-wage occupations like retail, food service, warehouse, and home care.

Who are minimum wage workers? At last count, 3.8 million workers are at or below the federal minimum wage. Some 10 times as many, 28 percent of all workers in the U.S., earn wages that would put a full-time worker below the official poverty level for a family of four ($11.06 an hour, or $23,050 per year).

Contrary to myth, more than three-quarters of minimum wage earners are not teenagers. Nearly two-thirds are women. One-third are Black or Latino. Two-thirds work part-time.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Tipped minimum. The federal minimum for tipped workers (in restaurants, car washes, and nail salons, for instance) has been stuck at $2.13 for 21 years. Originally the tipped minimum was a fixed 60 percent of the full minimum wage, but the restaurant industry persuaded Congress to uncouple it in the 1990s.

On paper, employers are supposed to make up the difference if tips don’t bring a worker up to full minimum wage each week, but the complex, poorly-enforced system makes tipped workers vulnerable to both error and wage theft.

Opponents of a minimum wage increase are among the biggest spenders nationally, OpenSecrets data show. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce has already spent $27 million on this year’s elections (mostly on ads urging people to vote against particular candidates), plus almost $3 million in direct contributions and another $55 million spent lobbying Congress so far this year.

Hospitals and nursing homes have racked up more than $23 million in contributions and spent $100 million lobbying. The food and beverage industry contributed $16 million and spent $27 million lobbying. The list reads like a roll call of low-wage employers, although unions are spending millions too in the effort to keep up.

LOCAL ORGANIZERS PUSHING

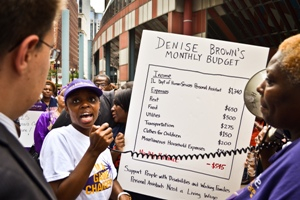

The campaign in Illinois is perhaps the most promising of the current statewide efforts. Action Now leads a coalition of labor and community organizations under the banner Raise Illinois, seeking a hike to $10.65 by 2014.

The groups have been gathering testimony from minimum wage workers, busing them to the capital to lobby their legislators, rallying, petitioning, and organizing house meetings in targeted districts. Governor Pat Quinn recently announced his support for the effort.

The group’s website features personal stories of life on minimum wage. One is nursing home worker Misty S., who has moved her family every few months in a vain effort to find someplace affordable. “Most of my paycheck goes to rent,” she says.

“We have three children and our paychecks combined barely cover the necessities like a roof over our heads, gas and lights, and clothes for the kids,” reports restaurant worker Edward A., whose partner also makes minimum wage. “We wouldn’t be able to make it without government assistance like food stamps and a medical card.”

THE USUAL OPPONENTS

Opposition is led by the usual suspects: the Restaurant Association, the Chamber of Commerce, the Retail Merchants’ Association. “It’s the same folks who line up against every pro-worker position that I know of,” Talbott said. “They’re always there saying that the sky will fall if we increase the wages at all. Then we increase the wages, and the sky doesn’t fall, and they say the sky will fall again the next time.”

The organizations united in Raise Illinois have faced down these businesses before and won repeated raises over the past decade, Talbott said. Illinois’s minimum is now $8.25.

One state, Rhode Island, passed a 35-cent increase this year, in a bill sponsored by a union nurse who serves in the state House. Voters in Albuquerque and San Jose will see increases on this year’s ballot. Legislative efforts are ongoing in New York, Connecticut, Delaware, and Massachusetts. And New Jersey voters may see a statewide referendum in 2013.

STILL NOT A LIVING WAGE

Labor plays a key role in many of these fights. The Service Employees were a major driver of the national day of action this summer and have linked the issue to the presidential campaign. SEIU highlights the minimum wage jobs at companies owned by Mitt Romney’s Bain Capital, like Dunkin’ Donuts, Toys “R” Us, and Burlington Coat Factory.

AFL-CIO state federations and local labor councils have been leaders of several of the state and city efforts. In other cases the driving forces are allies like the Working Families Party in Connecticut.

Talbott acknowledges that even the proposed Illinois minimum of $10.65 is far from a living wage.

But it would be a significant bump up. An Economic Policy Institute analysis of a similar proposal in 2011 found that the Illinois bill would affect over 1.1 million workers in the state, with a combined wage increase of more than $3.8 billion. That means an average of $3,500 more in the pocket of each minimum wage worker, most of them adults working full-time. Further, the new law would index the state’s minimum wage to inflation, making the gains permanent.

On a national scale, this year’s proposal to increase the federal minimum to $9.80 would raise pay for 28 million people, to the tune of $40 billion.

“It’s not enough, but it’s not bad,” Talbott said. “You still can’t live on it, but it’s more than you had before.”

This article is part of a set we're publishing this month, 'Making Elections Count for Labor.' Click here for other articles in the series.

/>

![Eight people hold printed signs, many in the yellow/purple SEIU style: "AB 715 = genocide censorship." "Fight back my ass!" "Opposed AB 715: CFA, CFT, ACLU, CTA, CNA... [but not] SEIU." "SEIU CA: Selective + politically safe. Fight back!" "You can't be neutral on a moving train." "When we fight we win! When we're neutral we lose!" Big white signs with black & red letters: "AB 715 censors education on Palestine." "What's next? Censoring education on: Slavery, Queer/Ethnic Studies, Japanese Internment?"](https://labornotes.org/sites/default/files/styles/related_crop/public/main/blogposts/image%20%2818%29.png?itok=rd_RfGjf)

You must log in or register to post a comment.