'We Took Care of Each Other': A Maritime Union's Hidden History of Gay-Straight and Interracial Solidarity

This detail from the comic below celebrates a period when workers on ships pushed wages up through powerful solidarity across race, gender, and sexual orientation. Graphic: Annabelle Heckler

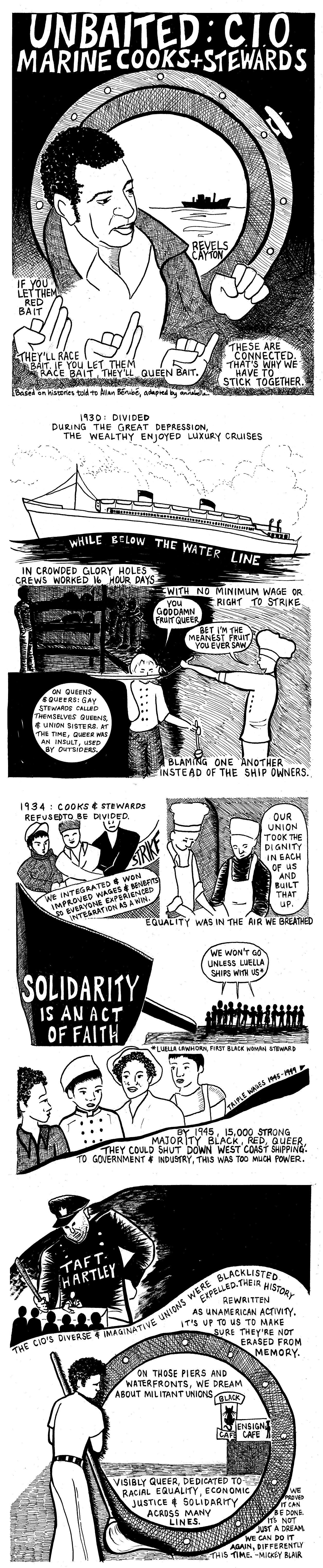

Decades before the modern LGBTQ+ movement, a small but militant union of maritime workers on the West Coast with openly gay members and leaders coined a slogan linking discrimination against gay men, racial discrimination, and red-baiting. For the better part of two decades, the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union fought discrimination on the ships where its members worked and in society, until it was crushed by the same corporate and government forces that tried to destroy the United Electrical Workers (UE) during the Cold War.

The Marine Cooks and Stewards Union (MCS) was formed in 1901 by the workers who waited on passengers, carried bags, cleaned rooms, cooked meals, and served drinks on the passenger and cruise ships that provided both travel and leisure for the middle and upper classes. They fed crews and washed the dishes and pots and pans on ships of all types. They faced grueling conditions, often being forced to work 16 hours a day, seven days a week, with no overtime pay, and sleeping in substandard quarters they called “floating tenements.”

Comic: ‘Unbaited’

by Annabelle Heckler

A pathbreaking solidarity that has been nearly erased from history comes to life in graphic form in Annabelle Heckler’s new comic “Unbaited: Marine Cooks + Stewards.” Click the image to view the comic full-size.

See more of Annabelle Heckler's work at @annabelleheckler on Instagram.

Many of the cooks and stewards were Black and Asian, but MCS, like too many unions at the time, restricted membership to white workers. And although a high percentage of the cooks and stewards were “queens,” as gay men preferred to call themselves at the time, the union rarely if ever stood up for them when they were taunted—or “queen-baited”—by straight workers.

This all changed during the great waterfront strikes of the 1930s, when both MCS and the longshore union, prodded by rank-and-file activists, realized the need to unite all workers in order to win against the powerful ship owners. Black and Asian workers joined the unions and the strikes, which were ultimately successful in establishing coast-wide contracts for MCS and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union—both of which joined the newly-formed Congress of Industrial Organizations.

Victory did not come without a cost. On July 5, 1934, known as “Bloody Thursday,” police killed two workers—a longshoreman and a cook—as the ship owners tried to reopen the port of San Francisco by force. The flowers at their graves were tended by an MCS member known as the “Honolulu Queen.”

‘IT’S ANTI-UNION TO RED-BAIT, RACE-BAIT, OR QUEEN-BAIT’

As MCS established its presence on the ships—and used its hiring hall to integrate formerly all-white crews—its members continued to face taunts and harassment for their sexual orientation, their race, and their politics from bosses, passengers, and members of the conservative Sailors Union of the Pacific.

Revels Cayton, a Black, straight steward who became an MCS official, told historian Allan Bérubé how the union worked to address this situation. “In 1936 we developed this slogan: It’s anti-union to red-bait, race-bait, or queen-bait. We also put it another way: If you let them red-bait, they’ll race-bait, and if you let them race-bait, they’ll queen-bait. That’s why we all have to stick together.”

Sticking together worked. Bérubé relates, “The insults keep coming, but the gay stewards are getting bolder because they know their union is watching their backs.” Stephen “Mickey” Blair, a white, gay MCS member told Bérubé, “Marine Cooks and Stewards took the dignity that was in each of us and built it up, so you could get up in the morning and say to yourself ‘I can make it through this day.’ Equality was in the air we breathed.”

A WALKOUT TO HIRE LUELLA LAWHORN

During World War II, the ships that MCS members worked on were converted to serve the war effort, carrying troops and munitions. MCS membership tripled. Many of the new members were gay men who want to serve their country in the fight against fascism but had been kicked out of the military for their sexual orientation. Bérubé writes, “Merchant seaman pay a high price during the war… Although they are civilians, they are killed at a higher rate than are servicemen in any branch of the armed services other than the Marine Corps.”

After the war, MCS continued its traditions of aggressive struggle and uniting all workers. Messmen’s wages tripled between 1945 and 1949. When MCS dispatched a Black woman, Luella Lawhorn, to work on the fancy passenger liner Lurline and the company refused to accept her, the entire stewards department walked off the ship. The company backed down, and Lawhorn became the first Black stewardess on a U.S. passenger ship in the Pacific. In 1949, recognizing that its white leadership didn’t reflect its multiracial membership (by 1949 more than half of the members were Black, and a significant number Asian), the union diversified its leadership within a year.

However, MCS soon fell prey to the same wave of Cold War repression that attempted to destroy UE, the ILWU, and other “Them and Us” unions. Along with UE, ILWU, and eight other unions, MCS was brought up on charges of “communist domination” and expelled from the CIO. The Coast Guard declared MCS activists as “security risks” and prevented them from taking jobs on ships. Other unions used homophobia and racism, as well as red-baiting, to try to destroy the MCS. Ultimately the union was absorbed into the conservative Seafarers International Union.

‘OUR HISTORY HAS BEEN ERASED’

Bérubé, who was working on a book about the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union at the time of his death in 2007, wrote that “Their history is unknown today because, through fear and intimidation, it was first rewritten as an un-American activity, then dismissed as an insignificant failure, and, finally, erased from our nation’s memory, as if what they had achieved had never even happened.”

“We were 50 years ahead of our time. We were so democratic this country couldn’t stand it,” Peter Brownlee, a white, straight MCS member told Bérubé. “The most important thing was not that we had gays. It was that an injury to one was an injury to all—and we practiced it. We took care of each other.”

Stephen Blair told Bérubé, “What many of you younger people are trying to do today as queers—what you call inclusion and diversity—we already did it 50 years ago in the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union. We did it in the labor movement as working-class queens with left-wing politics, and that’s why the government crushed us, and that’s why you don’t know anything about us today—our history has been totally erased.”

Jonathan Kissam is the communications director for the United Electrical Workers (UE). This article draws heavily on My Desire for History: Essays in Gay, Community, and Labor History, a posthumous collection of Bérubé’s essays published in 2011. A recording of the slideshow presentation about MCS that he gave to many union and community groups, “No Red-Baiting! No-Race Baiting! No Queen-Baiting! The Marine Cooks and Stewards Union from the Depression to the Cold War,” is available on Vimeo. Reprinted under the UE's materials reuse policy.