Review: Tearing Apart the Big Lies about 'Big Labor'

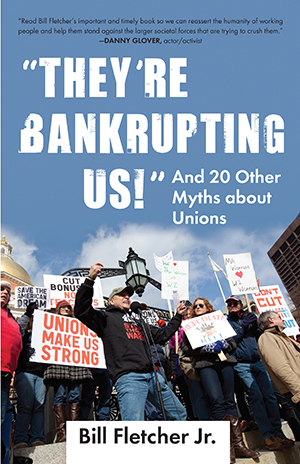

"They're Bankrupting Us!": And 20 Other Myths about Unions, 224 pages, $15, Beacon Press: 2012.

I started reading Bill Fletcher’s “They’re Bankrupting Us!” and 20 Other Myths about Unions on my way to Miami to sign up new members for the union. Florida is a right-to-work state and I was looking to recruit members in a largely conservative workforce in a big public hospital. I was inclined to believe I was in a scorched-earth situation.

As a union organizer, I’d heard these myths before. I had traumatic flashbacks with practically every page, and I started guessing which myths I’d hear from the workers first. “Unions are corrupt and mobbed up”? “Unions were started by communists and other troublemakers”? Or the title myth: “They’re bankrupting us and destroying the economy.”

These myths aren’t heard just by those of us knocking on doors for a union. They permeate popular culture.

I told a friend I was a union organizer once and he asked me if I was out breaking people’s legs. He was joking, but he got the idea from somewhere. And he certainly wasn’t able to tell me what I actually do.

As organizers, we’re equipped to have one-on-one conversations where we educate others on what a union actually is and the power solidarity can bring to a workplace. But this book is a great reminder of the sheer magnitude of what we’re up against. It isn’t a few people with some misinformation. It’s a complete rewriting of history based on an opposing interest.

The loudest narrative about organized labor comes from the other side. Fletcher critiques the mainstream media, using mogul Rupert Murdoch as just one example to show how business interests dominate the news and create hostility toward unions.

Fletcher’s book is an accessible and entertaining read that clearly outlines why unions are (still) relevant and, in fact, critical to movements for social justice, by dispelling the myths with compelling arguments rooted in history and personal experience.

His use of history goes beyond answering tough questions or dispelling myths in a tit-for-tat manner. Rather he takes the time to educate the reader on the impact that workers have had throughout our history and today in the fight against power imbalance and injustice.

Myth-Busting

For each myth, Fletcher starts with history and context first, giving background for what the myth is referring to and where it likely comes from.

Take the “Unions are mobbed up” claim. Fletcher uses the myth-busting opportunity to talk about where corruption stems from in any institution and how to fight it specifically in unions. Rather than denying the history of organized crime in labor and instances of corruption, Fletcher acknowledges it and reminds us that most unions don’t fall prey to it. Then he stakes out worker strategies to fight it.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

In good organizing, an organizer will validate a person before kindly letting that person know the facts. Though most of these myths stem from right-wing, pro-business nonsense, some have the blush of reality to them. Denying these realities, in my experience, does more harm than good. No one likes to feel lied to.

Fletcher understands this, and strikes a tough balance in defending unions while also offering a critique, shedding light on major contributions while also exposing missteps. Organized labor is responsible for the 40-hour work week, weekends, hiring equity in discriminatory industries like the docks, multiracial organizing (a major priority of the IWW in its prime), and community unionism that saw labor and local organizations working together to promote justice. But major missteps include servicing-oriented business unionism, an almost institutional link to the Democratic Party, and a departure from being a “cause” and a movement.

The systematic erosion of organized labor’s power by neoliberal policies, legislation, and attitudes is at the root of much of Fletcher’s myth-busting. But labor’s own response to these major ideological shifts in mainstream culture and politics was problematic.

Fletcher says union leaders deliberately departed from the “social vision that had accompanied the rise of labor unions.” Fletcher traces this shift back to Samuel Gompers, founder of the AFL, who called his rebranding “bread-and-butter” unionism, which would evolve into business unionism. The scope of unions narrowed to a particular set of needs for members (not workers in general) within a specific company or sometimes industry, but with no real connection to a larger movement, and not at odds with the capitalist system.

In the section that addresses the “Unions have a checkered history and were started by communists and other troublemakers” myth, Fletcher reflects on the positive influence radicals and leftists had on the labor movement and their subsequent persecution because of anti-communism. But the history is a distraction that misleads by promoting fear and panic, he argues, used to squash all organizing efforts that might shift the balance of power in favor of workers.

Move Past the Myths

How should we move forward, considering the difficult terrain? Fletcher offers specific strategies to return to a culture of solidarity among working people and their communities and restore the link between the labor movement and the fight against injustice. We should build associate membership categories in unions so non-union workers can join without having collective bargaining. We should organize outside the extremely limited Labor Board rules by joining with worker centers and becoming involved in community-based projects where organizations are organizing entire cities. The key is moving past the narrow framework of just one’s own union or workplace.

They’re Bankrupting Us! is a title that should be much appreciated by organizers and labor activists. New unionists should know where these myths come from, and seasoned ones can use the book’s renewed hope and sense of strategy to make those organizing conversations easier.

Fletcher reminds us how important it is both to educate others on labor’s history and to acknowledge our own shortcomings in order to grow this movement. He explores where we have to go and how to get there succinctly and superbly.

Michelle Crentsil is an organizer for the Committee of Interns and Residents, SEIU.