Even Without a Union, Florida Wal-Mart Workers Use Collective Action to Enforce Rights

Workers at Wal-Mart and other big-box retail chains--like workers in any mostly nonunion industry with low pay and tense, dreary working conditions--are generally a disgruntled lot. In central Florida, Wal-Mart workers are fighting and sometimes winning campaigns using collective action to solve both shop floor and larger industry-wide problems.

In one rural Florida town, over 20 percent of workers in the local Wal-Mart had their hours cut. In response, workers went into their community with a petition to reinstate the workers' lost hours, and collected 390 signatures in three days. Their hours were returned.

In South St. Petersburg, a popular third-shift employee was accused of theft and fired. The next day, half the day shift quit in protest. In another store, 20 workers marched on management after a 70-year-old workplace leader had her schedule changed. Her schedule was returned within days.

Several workers rode their bikes to work even though Wal-Mart didn't provide a bike rack. With some co-workers, they demanded management buy a bike rack. When management refused, they bought a rack with their own money and demanded that management install it. Management gave in, and donated the cost of the rack to a local charity.

BUILDING RESISTANCE

These actions were initiated and led by members of the Wal-Mart Workers Association (WWA), a growing group of 300 current and former Wal-Mart workers in over 40 stores.

"This is a protest movement of Wal-Mart workers uniting to make their lives better at work and in their communities," said Rick Smith, WWA organizer and Florida director of the Wal-Mart Association for Reform Now (WARN), a coalition of labor, community, homeowner, and anti-poverty groups. "It's about Wal-Mart workers sticking together, honoring their work, arranging carpools, and providing child care for each other."

Non-majority unions such as the WWA don't wait for a court to license workers' use of collective action. They harness that anger and ingenuity to both win day-to-day victories and launch longer-term pressure campaigns. The strategy has roots in industries in which union recognition is rare: retail chain workers, state workers, and computer programmers and manufacturers.

"We have the right to organization, regardless of what the boss or the state do," said Smith.

The WWA began in April with seed money from the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), the Service Employees (SEIU), the AFL-CIO, and ACORN (a community advocacy group). WWA members pay $5 in dues monthly.

Starting from scratch in mostly rural areas with low union density, WWA organizers knocked on doors in local communities to see if residents worked at Wal-Mart or knew anyone who did.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

The WWA and WARN have a strategic focus on central Florida. Wal-Mart is projected to saturate that area with as many as one store in every two miles, and double its supercenters there by 2010, according to WARN's research.

Rather than rejecting Wal-Mart completely, however, WARN and the WWA welcome the chain's low prices and access to goods--especially in inner cities--but demand that Wal-Mart meet standards set by the community.

WARN acts as the community pressure arm of the WWA and has already stopped five new Wal-Mart stores that don't meet its standards at the developmental review level, through its extensive research and mapping, strong coalition-building with diverse allies, and well-organized base in the community.

UNEMPLOYMENT CAMPAIGN

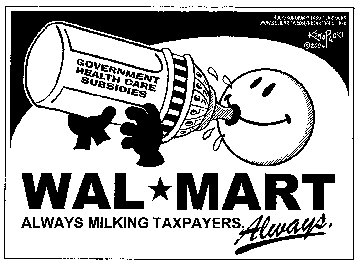

With 1.4 million employees worldwide, Wal-Mart is a driving force behind the push towards a part-time, on-call, at-will workforce. Seventy-four percent of employees work Wal-Mart's redefined 'full-time' 34-hour work week, making it even harder to pay for Wal-Mart's health care, and often forcing associates to find another job on top of unpredictable scheduling and family obligations.

Some Wal-Mart stores have enforced an 'open availability' policy, where supervisors ask employees to sign a document stating that they will be available for any shift at any time. Those who refuse, out of family obligations or self-respect, have been retaliated against with a cut in hours or firing.

To counter the widespread problems of inconsistent and under-scheduling, the WWA launched a campaign to encourage Wal-Mart workers to file for unemployment compensation.

Smith estimates that "hundreds, if not thousands" of Wal-Mart workers have filed for unemployment as part of the WWA's campaign. They usually win, according to Smith, costing Wal-Mart tens of thousands of dollars, and when they lose, they force Wal-Mart into a lengthy and revealing appeal process.

As a result, a number of Wal-Mart stores with higher levels of WWA member activity have changed their scheduling policy.

The WWA now has growing in-store organizing committees with leaders who have won grievances with management and still have their jobs and are partially compensated for their cut hours. No WWA member has, at press time, been fired for organizing.

The WWA has plans to expand and become the American Workers Association, a nationwide non-majority union for retail and other chain workers. A second chapter of the WWA recently began in Dallas, Texas.

Nick Robinson has worked at Wal-Mart and acted as a steward in the Montpelier Downtown Workers Union, a citywide non-majority union for retail and service workers. He works in a grocery store in Burlington, Vermont.